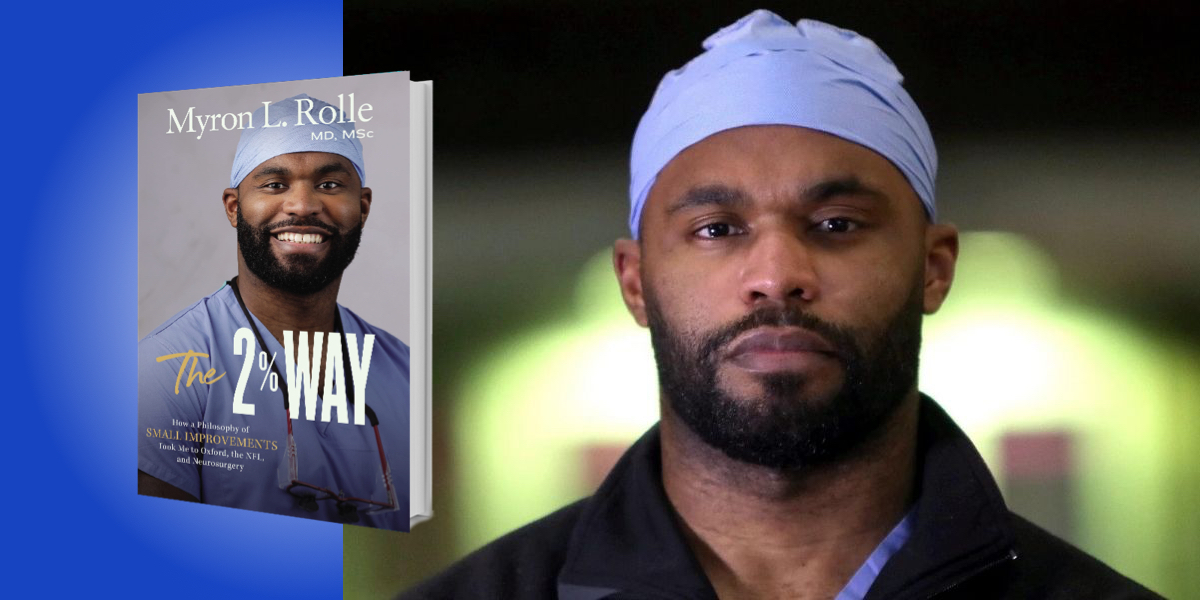

Dr. Myron L. Rolle is a former NFL safety, a Rhodes Scholar, and a neurosurgery resident and Global Neurosurgery Fellow at Harvard-Massachusetts General Hospital. His philanthropic work, academic excellence, and athletic endeavors have been featured in top global and national outlets such as CNN, ABC News, ESPN, and CNBC.

Below, Myron shares 5 key insights from his new book, The 2% Way: How a Philosophy of Small Improvements Took Me to Oxford, the NFL, and Neurosurgery. Listen to the audio version—read by Myron himself—in the Next Big Idea App.

1. Incremental improvements lead to bigger, longer-lasting results.

When I was a recruit at Florida State University, defensive coordinator Mickey Andrews demanded tangible progress, even if it was small, at every practice. He would yell at us players: “Someone at Alabama or Clemson is working just as hard as you. I need you to be 2% better than them in some way!” It was a football concept that originated with the legendary college coach Paul “Bear” Bryant.

Once I realized the power of the 2% Way in football, I extended it to every aspect of my life. For example, most people don’t realize that being able to perform in front of thousands of fans who watch every move is a unique kind of pressure. They don’t know that playing football primes you for neurosurgery. I personally learned that both require a kind of diligence that borders on fanaticism—for me, that involved making small, 2% changes every day to achieve the dreams that I wrote down in my 5th grade spiral notebook. The 2% Way can become the foundation for your success in life, too: modest increments, calibrated correctly, can make big dreams attainable, and immense progress possible.

2. Life is a journey, and you will grow from one station to the next.

Society doesn’t prepare athletes to think about life after football, but I learned that it is possible—and critical to athletes’ mental health—to have a blueprint for success off the field. Similarly, in other career fields, people may not stick with the same thing forever—they strategically diversify. There will be opportunities to leverage what you learned up to this point in the next chapter of your life. The skills, the traits, and the discipline that you have perfected—even in high school—can contribute enormously to being exceptional as you carve out your new path.

“There can be a new life that comes after the life you’ve always known fades away.”

I was drafted late (207th pick in the sixth round with the Tennessee Titans), and while people counted me out, it was a blessing in disguise because it always kept me focused on the fundamental, greater plan. Life always puts us in a position to make the most out of our situation. Next thing you know, I’m in medical school, becoming a neurosurgeon, preparing for a different kind of draft.

It’s easy to fall into the trap of thinking there’s nothing beyond what you’ve already done—your chosen major, your career up to this point, etc.—and you don’t create another plan. But there can be a new life that comes after the life you’ve always known fades away. And that doesn’t mean that changing your focus will eliminate the thing you loved most—for me it was football—or that it won’t be a part of your life in a different way.

3. Your name is what you make it.

When we Black people look into our past, we find that slavery and supremacy complicate our family stories. Lord John Rolle of England never set foot in the Caribbean, but that didn’t stop him from enslaving four hundred of my ancestors. They labored uncompensated on his Exuma plantation, sending generations of fortunes back to Europe.

When emancipation liberated his workforce in 1838, Lord Rolle lost interest in the Bahamas. Most freed slaves took up the surname Rolle and farmed his abandoned fields as their own. Today, around 60 percent of the island’s residents still carry the surname Rolle. I have aunties in Rolletown, and if you drive up and down Exuma’s roads, you’ll see a Rolle hair salon, a Rolle beauty shop, and Rolle convenience stores. The pain of slavery is calcified into my family name—but in the Bahamas, the word “Rolle” has been reclaimed. Now it is spoken in joy.

“Part of the Black experience is to transform the slights of the past into pride.”

Part of the Black experience is to transform the slights of the past into pride. When I return to the islands and hear the name Rolle shouted from the windows, or see it painted in blue and yellow on signposts, I feel like a son being welcomed back to the place where it all began. Your name is what you make it—and we’ve made it our own.

4. Be so good they can’t deny you.

As someone whose parents immigrated from the Bahamas, who was raised without wealth or luxury, I was taught from a very young age that the only thing that mattered was working hard and getting better. “Be so good they can’t deny you,” my father told me repeatedly. Because we didn’t have any other family around us, my parents taught us that we Rolles had to be our own cheerleaders.

But when I was ten years old, a kid called my family some terrible names, and I beat them up. This led to a court case in which I learned a difficult lesson: Don’t let others dictate your future.

5. Strive to make every month Black History Month.

Systemic racism continues to exist in America, and I’ve witnessed firsthand how overcoming it continues to be a monumental task—one that’s impossible to confine to just 28 days of the year. The structurally violent system is still a daily reality for Black Americans, regardless of whether it’s highlighted in the news for non-Blacks that day. Systemic challenges are written into the rules, and they prevent true equality.

“We need to decide that we are going to move the needle ever so slightly, every day.”

I see this dynamic at play in the hospital where I work. I have the pleasure of working with truly amazing colleagues—doctors, nurses, and administrators who welcome me as part of the team and treat me as a cherished colleague and a dear friend. But there have been instances when I’ve walked into a room, and a patient has brought me back down to where I was scared to be. I’ve been mistaken for a food delivery man, a member of the cleaning staff, or otherwise assumed to be someone who couldn’t possibly be part of the neurosurgery crew. It’s frustrating to continue to get stereotyped in that respect. Simply because I’m Black existing amid a white majority—even when I’m dressed in scrubs—my presence is often mistaken for being someone who will serve your lunch, not save your life.

So how do we move forward? How do we mitigate the systemic challenges that oppress, even when we have allies who want to help? Instead of thinking about the system as a large, overwhelming, megalithic entity, we must break it down into small pieces. We need to decide that we are going to move the needle ever so slightly, every day. By reading more, by advancing policy, by communicating, and by investing in younger people, we can break the mold.

We could look at all the work still ahead of us and feel powerless, or angry, or desperate. We could focus our energy on demanding that entire industries, companies, and communities overhaul the way they go about their business. Or we could apply the only methodology that succeeds in achieving real growth over time, and challenge ourselves—and those around us—to notice just one small injustice a day, or take one step toward self-awareness and improvement each week.

To listen to the audio version read by author Myron Rolle, download the Next Big Idea App today: