In 2011, a college senior named Meredith Perry noticed that something very basic was wrong with technology. She didn’t need a cord to make phone calls or connect to the internet. Everything that used to be wired was now wireless . . . except for one thing. To use her phone and her computer, she had to plug them in. She wanted wireless power.

She started thinking of things that could beam energy through the air. The signal in a TV remote was too weak, radio waves were too inefficient, and X‑rays were too dangerous. Then she came across a device that could convert physical vibration into energy. If you put it under a train, for example, you could collect the energy the train generated.

Although it wasn’t practical to have people gathering near trains to capture their energy, she realized that sound travels through the air by vibration. What if she could use ultrasound, which is invisible and silent, to generate air vibrations and convert them into wireless power? Her physics professors said it was impossible. Some of the world’s most respected scientists told her she was wasting her time.

Three years later, I met Perry at a Google event. After landing $750,000 in seed money from Mark Cuban, Marissa Mayer, and Peter Thiel’s Founders Fund, her team had just finished its first functional prototype. It could power devices faster than a wire, at longer distances, and would be ready for consumers in two years. By the end of 2014, her company, uBeam, had accumulated eighteen patents and $10 million in venture funding. Debate continued about how well the product would work, but she had overcome the fundamental barrier to proving the viability of the technology. “Every single person that is now working for the company didn’t think it was possible or was extremely skeptical,” Perry said.

Meredith Perry faced an extreme version of the struggle we all face in championing original ideas: overcoming skepticism. Her initial efforts fell flat. She reached out to scores of technical experts, who were so quick to point out the flaws in the math and physics that they wouldn’t even consider working with her. It probably didn’t help that she was offering to hire them as contractors on deferred payment—they might never see a check.

Researchers Debra Meyerson and Maureen Scully have found that to advance new ideas, original thinkers need to become tempered radicals. That means presenting your bold vision in ways that are less shocking and more appealing to mainstream audiences. And it made all the difference for Meredith Perry.

She did something that flew in the face of every piece of wisdom she had heard about influence. She simply stopped telling experts what it was she was trying to create. Instead of explaining her plan to generate wireless power, she merely provided the specifications of the technology she wanted. Her old message had been: “I’m trying to build a transducer to send power over the air.” Her new pitch disguised the purpose: “I’m looking for someone to design a transducer with these parameters. Can you make this part?”

The approach worked. She persuaded two acoustics experts to design a transmitter, another to design a receiver, and an electrical engineer to construct the electronics. “In my head it all came together,” Perry recalls. “There was no other way, given my knowledge and skill set.” Soon she had collaborators on board with doctorates from Oxford and Stanford, with math and simulations confirming the idea was viable in theory. It was enough to attract a first round of funding and a talented chief technology officer who had initially been highly skeptical. “Once I showed him all the patents, he said, ‘Oh sh*t, this actually can work.’ ”

In a popular TED talk and book, Simon Sinek argues that if we want to inspire people, we should start with why. If we communicate the vision behind our ideas, and the purpose guiding our products, people will flock to us. It’s excellent advice—unless you’re doing something original that challenges the status quo. When moral change agents explain their why, it runs the risk of clashing with deep-seated convictions. When creative geniuses explain their why, it may violate common notions of what’s possible.

Meredith Perry won over investors and employees by becoming a tempered radical. When she couldn’t persuade technical experts to take a leap with her, she convinced them to take a few steps by masking her purpose. She made her implausible idea plausible by hiding its most extreme feature. So next time you have a radical new idea, try toning it down.

***

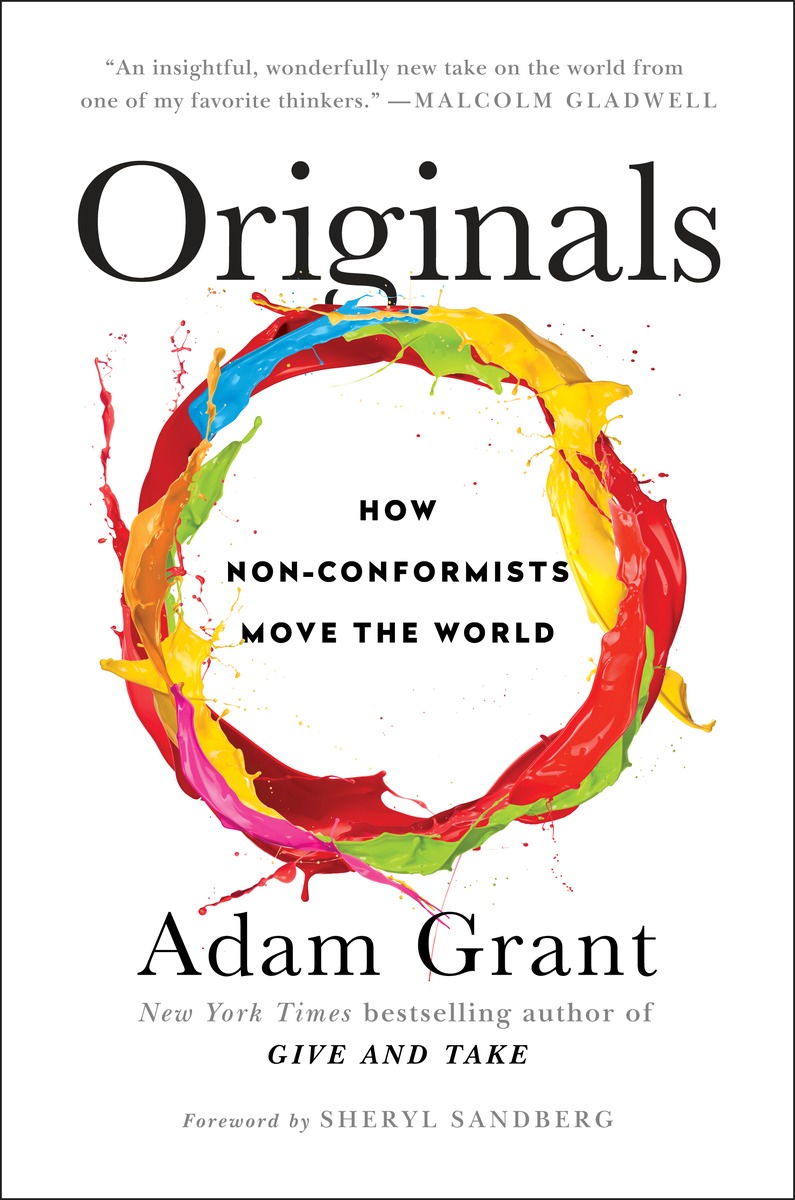

This post is adapted from Adam’s new book Originals: How Non-Conformists Move the World. To test your knowledge about what it takes to be original, try his free 5-minute quiz here.