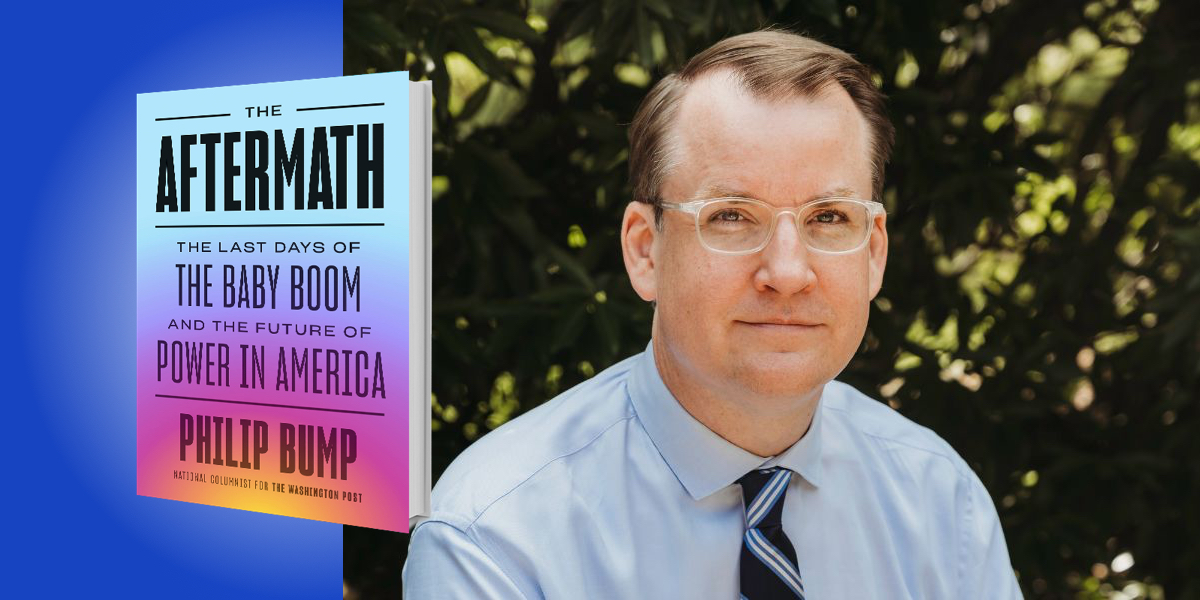

Philip Bump is a national columnist for the Washington Post; before that he led political coverage for The Atlantic Wire. One of the paper’s most read writers, he focuses on the data behind polls and political rhetoric.

Below, Philip shares 5 key insights from his new book, The Aftermath: The Last Days of the Baby Boom and the Future of Power in America. Listen to the audio version—read by Philip himself—in the Next Big Idea App.

1. The baby boom was more enormous than you may realize.

It’s easy to misunderstand how precedent-breaking the generation’s size actually was.

For the U.S. to see population growth equal to the surge that began in the mid-1940s, the number of births in the country at this point would need to nearly triple. The year before the boom began, the population of the United States was about 140 million. Over the next 19 years, 76 million babies were born—more than half the total number of Americans before the boom began.

The effect was to create a massive new economy that traveled along with the boomers. There was suddenly a glut of babies, so businesses selling diapers or bronzing shoes saw a boom time. Then there was a crush to build schools to accommodate all the kids, with Los Angeles averaging one new school a month over the duration of the boom. And then the glut of consumers became voters and workers, and those things shifted, too.

2. The divide between boomers and millennials runs a lot deeper than age.

The generational tension in America today, where older people are frustrated at what younger people are doing, follows a pattern that’s likely as old as humanity itself. But there are other differences between the boomers and younger generations that contribute to the tension we now see.

First and foremost, the baby boom generation is much more densely white than younger Americans. The boom emerged at a time when American immigration was legally constrained; the typical immigrant living in the U.S. was someone’s grandparent. At the end of the boom, immigration was loosened, contributing to the increase in Asian and Hispanic Americans.

“Young people can make themselves heard and seen in ways that older Americans couldn’t.”

Younger Americans are also better educated and less religious than older ones, contributing to both cultural and political differences between the two groups.

But there’s another factor to consider, too: Technology. When boomers were teenagers, they were a focus of outsized attention, but their ability to redirect the country’s attention was contingent upon older gatekeepers in the media or other industries. Now, as one PR person told Harper’s a few years ago, “You can be in Cleveland, Ohio, alone in your bedroom, and you

can get a million followers overnight.”

Young people can make themselves heard and seen in ways that older Americans couldn’t. The difference in power that defines traditional generational disputes has been upended. As much as boomers might like to ignore millennials, they often can’t.

3. America may become majority-minority soon—or perhaps it already is.

For years, demographers have plotted the point at which white Americans drop below 50 percent of the population. But our common understanding of America’s demographic evolution—and perceptions about the evolution that undergird a lot of the political divide—is overly simplistic.

The Census Bureau projects that non-white Americans will be a majority within the next two decades. But those projections, it turns out, depend on assumptions about how people identify their own race that may not hold up over time, as research has shown. Will the children of Hispanic Americans also identify as Hispanic? Or might they identify, as an increasing number of Americans do, as mixed-race? Or will they identify as white?

“We are already well into a transition to a less rigidly divided racial delineation, one that reduces the importance of the majority-minority transition.”

Recognizing the complexity of racial identity, the Bureau has expanded the way in which it allows people to record their racial and ethnic backgrounds, contributing to the decline of Americans who solely identify as “white”—or, in keeping with government standards, “white non-Hispanic.” We are already well into a transition to a less rigidly divided racial delineation, one that reduces the importance of the majority-minority transition.

But recall that the baby boom arrived at a time when immigration was at an historic low and when “not white” meant “Black.” America does look different than it did when baby boomers were young and that alone has an obvious effect.

4. Baby boomers are already shedding trillions of dollars of assets, but it’s not clear who will benefit most over the long term.

Baby boomers are much wealthier than other generational groups, but there’s an important caveat: There are also far more of them. The scale of the boom and America’s wide wealth inequality means that most boomers aren’t particularly wealthy at all.

That said, as boomers get older, retire, and begin to die, they will increasingly transfer their wealth to others. Some will be bequeathments. Some will be spending on younger family members and friends—paying for houses or college, for example. One financial firm estimates that boomers were passing along about $2 trillion annually as of last year.

But how much they will pass on to family or to organizations depends on a fairly macabre question: how long they live and how healthy they remain. That Americans live longer today than they did a century ago is good news, certainly. But it also means that there are more years that boomers can spend down their wealth—or, in more dire circumstances, will have to spend their wealth on things like expensive health care or specialized housing.

“The scale of the boom and America’s wide wealth inequality means that most boomers aren’t particularly wealthy at all.”

One thing economics experts assured me of, though: the families of the wealthy will land on their feet. After all, they’ve often been the focus of interfamily spending for most of their lives.

5. The state that best matches America’s 2060 demography? Florida.

In the abstract, this seems like nothing more than a bit of trivia. If we compare the Census Bureau’s demographic projections for 2060 to America today, the state that most closely mirrors the age and racial composition of the U.S. in 40 years is Florida.

But then consider what that means. For all of the discussion about how America’s changing demography will advantage Democrats, Florida is already heavily diverse—and regularly votes Republican. One political consultant I spoke with marveled at the fact that the state continuously defied expectations that its demography meant it would shift to the left.

He also cautioned against trying to look too far into the future, which is certainly fair. But that younger Americans are so much more heavily Democratic—and consistently so—will mean they’d have to shift to the right dramatically as they get older. Conventional wisdom suggests that this is the expected pattern, but that wisdom is itself not terribly old, and it’s built around a younger generation of Americans that’s far less diverse than young Americans are today.

As with the shift of economic power, the shift in political power that follows the baby boom will depend to a significant extent on the decisions we make and the policies we implement today.

To listen to the audio version read by author Philip Bump, download the Next Big Idea App today: