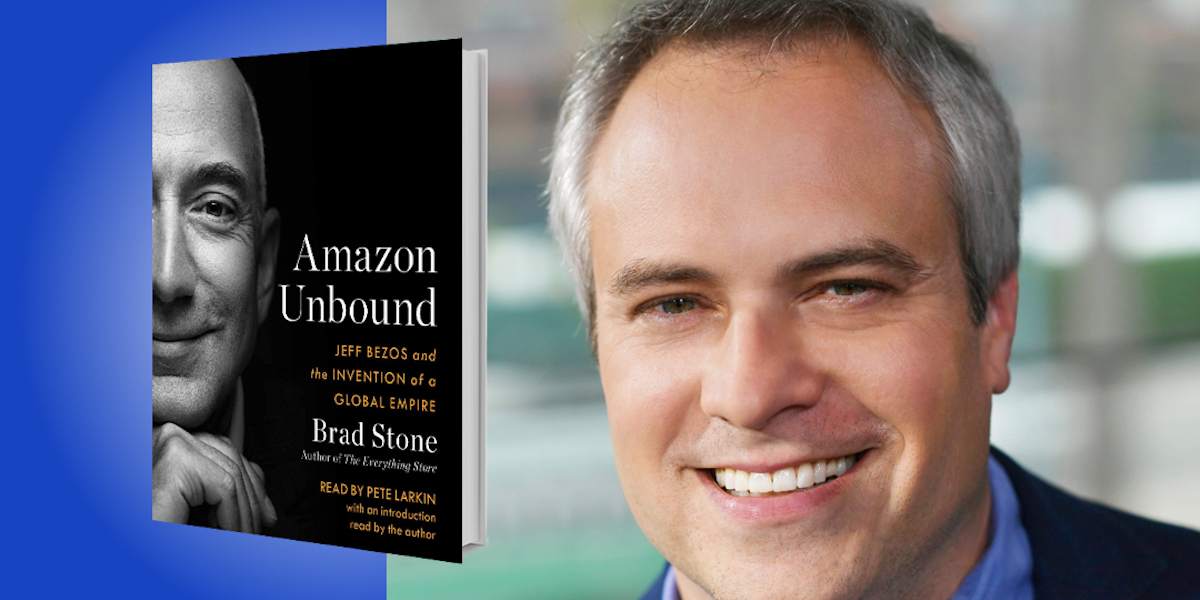

Brad Stone is a senior executive editor at Bloomberg News. His previous book, The Everything Store: Jeff Bezos and the Age of Amazon, was a New York Times bestseller, won the 2013 Financial Times/Goldman Sachs Business Book of the Year Award, and received a one-star review on Amazon from MacKenzie Scott.

Below, Brad shares 5 key insights from his new book, Amazon Unbound: Jeff Bezos and the Invention of a Global Empire (available now from Amazon). Listen to the audio version—read by Brad himself—in the Next Big Idea App.

1. Leaders must drive disruptive new products inside their companies.

In 2010, Jeff Bezos was simultaneously impressed by advancements in voice recognition and hungry to capitalize on Amazon’s advantage in cloud computing. Those two things overlapped when he sent an email to an executive. He wrote, “We should build a $20 computer whose brains are in the cloud, completely controllable by your voice.” Over the next few years, he met with the team making the first Echo multiple times a week. He set goals and walked out of meetings when they weren’t met. He personally selected the names Echo and Alexa, and tested the device in his own home. After the first Echo was released, he asked the leader of every division inside the company, “What are you doing for Alexa?”

A company-defining product like Alexa—and the Kindle and AWS—wouldn’t have been possible without Bezos’s direct involvement. He cleared away the bureaucratic thicket inside the company and encouraged his deputies to be unbound in their ambition.

2. Great leaders change altitudes.

People often conclude that Jeff Bezos is an intolerable micromanager, but that’s not always the case. When it comes to the large divisions at Amazon, like retail and cloud computing, he prefers to hover above them, allowing his deputies to operate with considerable freedom. But every so often, he swoops down without warning and takes a close look, analyzing problems and insisting on strategic changes.

“It’s a classic example of a CEO suddenly changing altitudes, swooping down to audit the business in order to keep the company on track.”

In an executive meeting in 2017, Bezos was reviewing the operating plan of retail and saw something that worried him: Retail was blending Amazon’s new and growing advertising revenues into its financial projections. Without ads, its underlying profitability was actually decreasing. Bezos demanded the group’s executives sit there and recalculate their numbers. Then he insisted on dramatic changes in their operating plans to cut costs and return the unit to profitability. It’s a classic example of a CEO suddenly changing altitudes, swooping down to audit the business in order to keep the company on track.

3. Amazon builds new businesses with people. But when those businesses grow, Amazon runs them with algorithms.

In Amazon’s fulfillment centers, warehouse robots and algorithms ruthlessly monitor employee performance. In Amazon’s new supermarkets, ceiling-mounted cameras and AI software track what you buy, so a cashier doesn’t have to check you out. And in the company’s advertising division, sellers can sign up and advertise their listings without ever talking to a human being. These systems, even when designed with good intentions, are often gamed—and that can have negative repercussions for customers, and for society.

Take the marketplace, which lets independent sellers hawk their wares on the Amazon site. Back in 2007, the marketplace was already a few years old, but it was basically just a dusty repository for used books. Bezos was so frustrated by the lack of progress that he tore up the team’s documents in an annual planning meeting. “How,” he asked, “would you get a million sellers into this marketplace?”

Executives understood that there was only one answer to Bezos’s question. You couldn’t possibly reach out to sellers and recruit a million of them one by one; you would have to build a self-service machine that encouraged sellers to come to Amazon.

So that’s what Amazon did. A tool called Seller Central became a self-service platform for third-party vendors. Selection exploded, prices declined, and all sorts of chaos rained down on Amazon—fraudulent products, counterfeits, hoverboards that exploded when they were plugged in, and fake books filled with gibberish. And Bezos loved it, despite the customer-experience headaches. He applauded his team for building a self-service platform that generated high-margin revenue growth.

“Today’s dominant company could be tomorrow’s fading giant—that’s why Amazon is constantly trying new things.”

4. Companies need to earn a social license to operate in the communities where they are visible.

By 2017, Amazon’s relationship with Seattle was growing turbulent. The company’s local headcount had grown faster than anyone had expected or planned for, and it was being blamed for ills like gentrification, rising home prices, and homelessness. At the same time, Amazon conducted little local philanthropy, beyond moving a homeless shelter onto its downtown campus. The company didn’t and still doesn’t match employees’ charitable contributions. Bezos appears to believe that employing tens of thousands of workers and paying local taxes is enough of a contribution.

So as the progressive city council turned against Amazon, Bezos started looking elsewhere to expand, initiating the HQ2 process. You probably remember the outcome: Amazon selected the Long Island City neighborhood of Queens, which was offering $3 billion in tax incentives, and ran headlong into even more intense resistance than it had encountered in its hometown. Critics saw Amazon as an arrogant newcomer, one that was extracting from, rather than adding to, New York City. In other words, the company hadn’t earned a social license to operate in town, and eventually had to retreat ignominiously.

5. The future belongs to the relentless.

There’s a general attitude inside Amazon that there are no annuities in the tech world—today’s dominant company could be tomorrow’s fading giant. That’s why Amazon is constantly trying new things, expanding into large markets, and redefining itself in the eyes of its customers. This kind of relentlessness—a continuous exploration, never staying still—explains why the company is so interesting to watch. And it was Jeff Bezos who seeded that relentless approach, which he calls “Day One mentality,” into the DNA of the company.

To listen to the audio version read by Brad Stone, download the Next Big Idea App today: