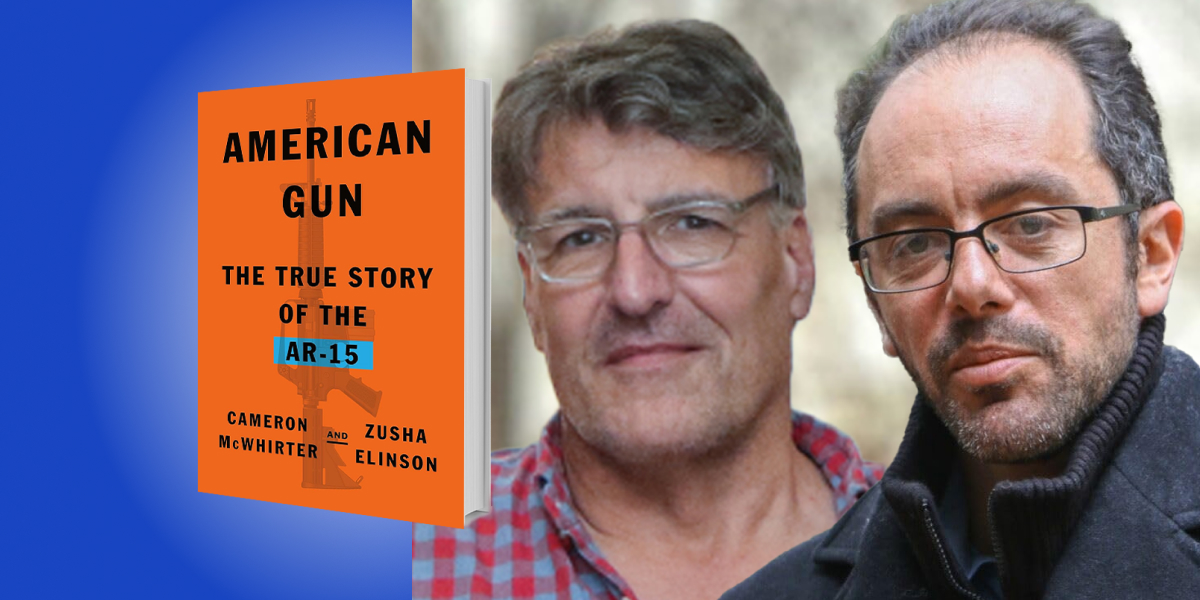

Cameron McWhirter is a U.S. News reporter for The Wall Street Journal. Zusha Elinson is a national reporter, covering guns and violence, for The Wall Street Journal.

Below, co-authors Cameron and Zusha share 5 key insights from their new book, American Gun: The True Story of the AR-15. Listen to the audio version—read by Cameron and Zusha—in the Next Big Idea App.

1. True innovators are hyper-focused on specific problems and see them in ways that conventional thinking hasn’t.

Eugene Stoner, the inventor of the AR-15 rifle, never went to college and had no formal training in engineering or gun design. Instead of limiting him, this gave him the freedom to try ideas that others wouldn’t consider. For centuries, gunmakers had built rifles out of wood and steel, making them very heavy. As he tinkered with guns in his Los Angeles garage, Stoner wondered if he could use the lightweight modern materials that were becoming popular at this time in the 1950s. He had worked with aluminum for years as a machinist making aircraft parts. If humans were taking flight using this lightweight material, could aluminum tolerate the pressures of firing a gun?

One of his major innovations was to use aluminum instead of steel to make a critical piece of the rifle. He, along with colleagues at a small firearms company, also used fiberglass and plastic instead of wood for other parts.

Stoner’s mind never stopped. He sketched gun designs on everything he could find. Out to dinner with his family, his wife would scold him for drawing on the white linen tablecloths. “They can wash it out,” he would say. He devised clever ways of using the force of hot gas from the exploding gunpowder to move parts inside the gun to eject spent casings and load new rounds. In doing so, he eliminated several cumbersome metal parts. At first, his new system blew hot gas right into his face when he fired the gun, but he perfected it and eventually patented it. The result was a rifle that was futuristic, lightweight, and remarkably easy to shoot. As Stoner later said, “It looked a little far out for that time in history.”

2. Inventors are often only fixated on the problems before them, not the long-term consequences of their inventions.

Stoner was relentless in developing the new type of rifle he believed would help the U.S. military and its allies facing communist insurgents during the Cold War. He overcame engineering challenges, avaricious colleagues who tried stealing his ideas, and strong resistance from elements of the military that wanted their more traditional rifles adopted. Stoner was trying to create a rifle that was light, easy to shoot, and would allow soldiers to carry more ammunition into the field. He wasn’t thinking about how his rifle would be altered or misused by the military and others in the decades to come.

“Invention leads society to places it didn’t plan to go.”

The same design attributes that made it a great weapon for that time and purpose also made it perfect today for mass shooters: it requires little or no training in firearms and wreaks havoc in minutes. J. Robert Oppenheimer, the lead developer of the atomic bomb, said, “When you see something that is technically sweet, you go ahead and you do it, and you argue about what to do about it only after you’ve had your technical success.”

Invention leads society to places it didn’t plan to go. Only after the invention is with us does society realize it has to solve problems arising from its arrival. Thoughtful discussion, compromise, and consensus solve those problems. Delay, lack of understanding, and bitter political battles make the problems worse.

3. Ideas are cheap, creation is hard.

Anyone can dream up the next great invention. Much of our book explores how Stoner’s invention became a lethal handheld icon of the American century. It is a story that involves presidents from Eisenhower to Biden, bickering generals, schmoozy businessmen, a renegade spy, bullet-ridden goats, desperate soldiers, cult members, partisan senators, a tap dancer turned gun maker, a gun-obsessed hedge fund king, mercenary admin, a brigade of lobbyists, disturbed killers, and the victims.

At a key moment in history, when it seemed that Stoner’s rifle would be killed off by military bureaucrats, a powerful cigar jumping air force General, Curtis LeMay, was asked if he wanted to shoot the gun at a party. Lobbyists for the rifle’s manufacturer set up three ripe watermelons and LeMay fired, causing a red and green explosion. He marched into the Pentagon soon after and demanded that the military purchase the weapon, which would become the Army standard issue rifle, the M16.

Today, the semi-automatic version of Stoner’s gun is the most popular rifle in America, but for a long time, it was a niche product that was despised by traditional hunters and mainstream gun makers. Cultural and political shifts after 9/11 transformed the rifle. Americans wanted to own the gun that was being carried by soldiers fighting terrorists in the Middle East. The 10-year federal assault weapons ban ended in 2004, making it palatable for mainstream American gun makers to sell AR-15s.

“For a long time, it was a niche product that was despised by traditional hunters and mainstream gun makers.”

Politics supercharged the market as the rifle became a symbol of Second Amendment rights, and gun owners rushed to buy AR-15s, fearful that Democrats would ban them. Stoner was never interested in the commercial sales of his rifle. He wasn’t a businessman. When he died in 1997, none of his obituaries even mentioned the civilian version of the weapon. Today, more than 20 million Ars have been sold to Americans, the majority in the past decade. The gun has also been embraced by disturbed loners, bent on going to war with society. They used stoner’s rifle to attack Americans in movie theaters, grocery stores, schools, parades, or anywhere people gather. It was the opposite of what Stoner wanted. Instead of protecting Americans, it was killing them. Inventors ultimately have little control over how their inventions are used.

4. The moral responsibility of inventors is complicated.

Asking what responsibility inventors owe to society is important. What would Stoner and his colleagues who designed the AR-15 think about how their creation is being used today? We spoke with the last living member of the team that worked on the gun. We spoke with Stoner’s family and friends. They all offered profound insights on this delicate question.

5. Inventions inherently have unintended consequences.

To go back to Oppenheimer, the AR-15 was “technically sweet” but now society is left to argue about its impact on the world. The AR-15 has left its quiet, modest inventor with a strange and bloody legacy. All inventions have unintended consequences: automobiles, smartphones, television, social apps, you name it. Now everyone is talking about artificial intelligence. Inventions pull societies in directions they often weren’t prepared to go. The perpetual challenge for any society, and certainly for American society, is to find consensus and solve the unforeseen problems that arise from inventions.

Americans have done this in the past with a host of inventions. For the AR-15, there have been a range of laws, security measures, and other strategies formed to make us safer in a world where Eugene Stoner’s invention is everywhere. But society can’t yell its way out of this crisis, it has to compromise and accept that the technology is here to stay.

To listen to the audio version read by co-authors Cameron McWhirter and Zusha Elinson, download the Next Big Idea App today: