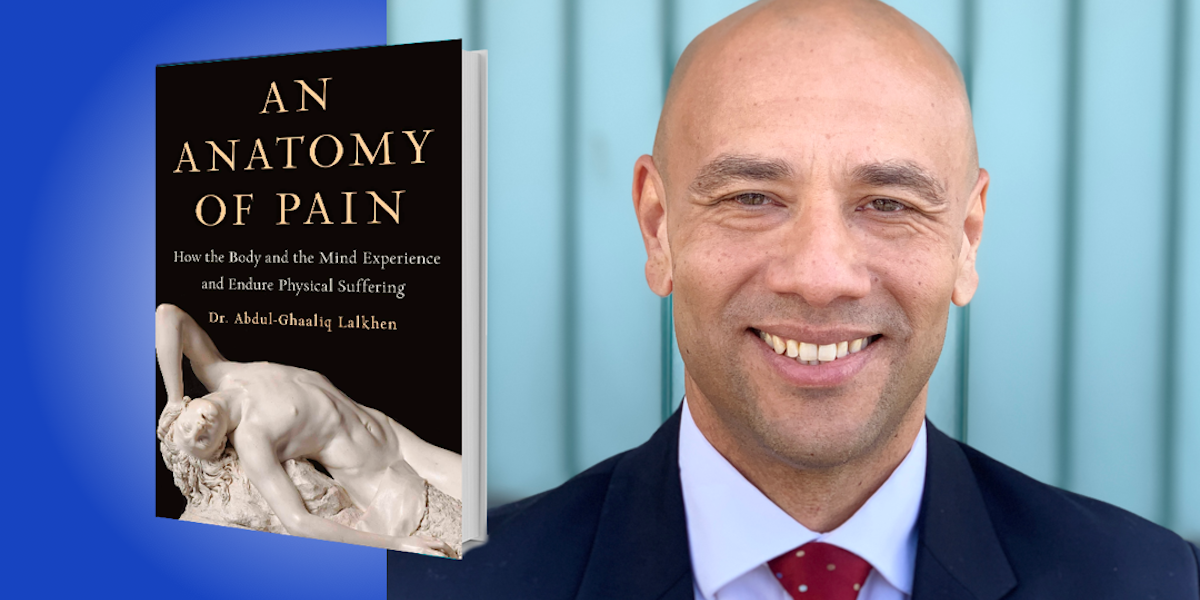

Dr. Abdul-Ghaaliq Lalkhen has been working in pain-related areas—from anesthesiology to pain management—for over two decades. He is a member of the Faculty of Pain Medicine affiliated to the Royal College of Anesthetists and a Visiting Professor at Manchester Metropolitan University.

Below, Abdul-Ghaaliq shares 5 key insights from his new book, An Anatomy of Pain: How the Body and the Mind Experience and Endure Physical Suffering (available now on Amazon). Download the Next Big Idea App to enjoy more audio “Book Bites,” plus Ideas of the Day, ad-free podcast episodes, and more.

1. Different people experience pain very differently.

During a game on March 14, 2010, soccer star David Beckham ruptured his Achilles tendon. Immediately after the tear, it appears that he didn’t realize how badly he had injured himself. He even tried to run up and kick the ball, but couldn’t—after all, his calf muscle was no longer attached to his ankle. At that moment, however, it doesn’t seem that he was in much pain.

I often use Beckham’s example to explain the difference between tissue damage and pain. Similarly, soldiers injured in battle sometimes do not complain significantly of pain, even in the presence of horrific injuries. Their immediate concern is to get to safety, and the brain can override the experience of pain to facilitate that goal. In 1981, president Ronald Reagan was shot in the chest, but he recalled later that he only realized he had been shot when he saw the blood seeping through his shirt on his way to the hospital.

Pain is influenced by beliefs and expectations, as well as psychological factors such as mood and resilience. An individual’s culture, genetics, and innate ability to cope with adversity will also impact on their experience of pain. In short, different people experience pain very differently.

2. Pain sometimes persists even when we cannot find ongoing damage.

I first met Helen on a Saturday when she came to my pain clinic. She told me about pain all over her body on most days of the week. She always felt tired, she couldn’t remember things well, and she often had episodes of low mood for no reason. I diagnosed Helen with a condition called fibromyalgia syndrome, which is associated with widespread, nonspecific, and often confusing pain. Fibromyalgia is an example of a chronic pain condition, a disease of pain where there has been a change in the way the nerves function. Some of our patients have chronic pain due to a disease like diabetes, which can cause nerve damage. Other patients have non-specific lower back pain.

“Pain is influenced by beliefs and expectations, as well as psychological factors such as mood and resilience.”

Medications, injections, or electrical devices inserted into the body can reduce the volume of chronic pain. But what is more important are psychological techniques such as mindfulness, which aims to help the person live their life despite this blaring alarm of pain. Some people have lost bodily function because they’re afraid to move, thinking that their pain was due to ongoing damage. But physical therapies can help them regain their function.

3. For every complicated problem like pain, there is a solution that is clear, simple, and wrong.

Pain has been our constant companion throughout our history as a species, and relief from pain and suffering has been chased relentlessly. (The word “pain” means “punishment” or “vengeance” in Greek.) However, most people do not appreciate that the organ that produces pain is the brain—not the broken bone or the damaged tissue or the bleeding wound. We have a collective delusion that the human body is a simple machine that can be repaired by the medical profession when it breaks down. But pain is an experience, which is not simply a manifestation of a dysfunctional machine.

We have a tendency to medicalize pain, and we often apply excess amounts of simple solutions, such as opioids or surgery, in order to stop pain. But too often, these interventions do nothing to improve the functioning of the body, and can actually cause significant harm. So perhaps we need to stop viewing our bodies as simple machines that medicine can fix when they go wrong. Instead, education about the complexity of pain, as well as the non-pharmacological and non-surgical factors involved, may go a long way to improving quality of life.

“We ruin our health in search of wealth—to seek, to have, to save—and then we spend our wealth in search of health, only to find the grave.”

4. Opioids: the lessons not learned.

Opium was widely used in the ancient world, with the Sumerians growing poppies as early as 3400 BCE. They called it the “joy plant.” The Persians understood that opium could provide pain relief, suppress your cough, muddle your mind, and inhibit your ability to breathe. Morphine, named after the ancient Greek god of dreams, was first synthesized in Germany in 1804, and was produced in industrial quantities in the 1820s. In the US, opiates were not regulated at all until the Harrison Narcotics Tax Act of 1914. In fact, the Sears and Roebuck catalog offered morphine and the syringe for just $1.50, and headache powders containing opium were available over the counter.

It wasn’t until the mid-19th century that doctors began to realize that the regular use of morphine had negative effects. Heroin was first synthesized in 1874 as a less addictive alternative to morphine, and a hundred years later, oxycodone was synthesized as a less addictive form of morphine. The current opioid epidemic demonstrates our destructive tendency to treat the complex experience of pain with medication, in the absence of a clear understanding of the myriad chemical interactions that underpin this phenomenon.

5. Aging is inevitable, but pain and suffering are not.

There is an adage that goes, “We ruin our health in search of wealth—to seek, to have, to save—and then we spend our wealth in search of health, only to find the grave.” The nervous system changes as we get older, and this has significant implications for the experience of pain. Older patients may report less pain, or pain in a different distribution, compared to young adults with the same clinical problem. Chronic pain has a significant effect on patients who are older, resulting in a reduction in mobility and the avoidance of certain activities. These individuals may also fall because they can’t rapidly change position. Given the potential negative effects of medication or other interventions, it’s important for older adults to access rehabilitation therapies in the form of behavioral interventions and physical reactivation. Failure to address loss of function in the elderly leads to depression, anxiety, and the disruption of social relationships. Chronic pain in older adults places a significant burden on the communities within which they live, and results in increasing social isolation.

For more Book Bites, download the Next Big Idea App today: