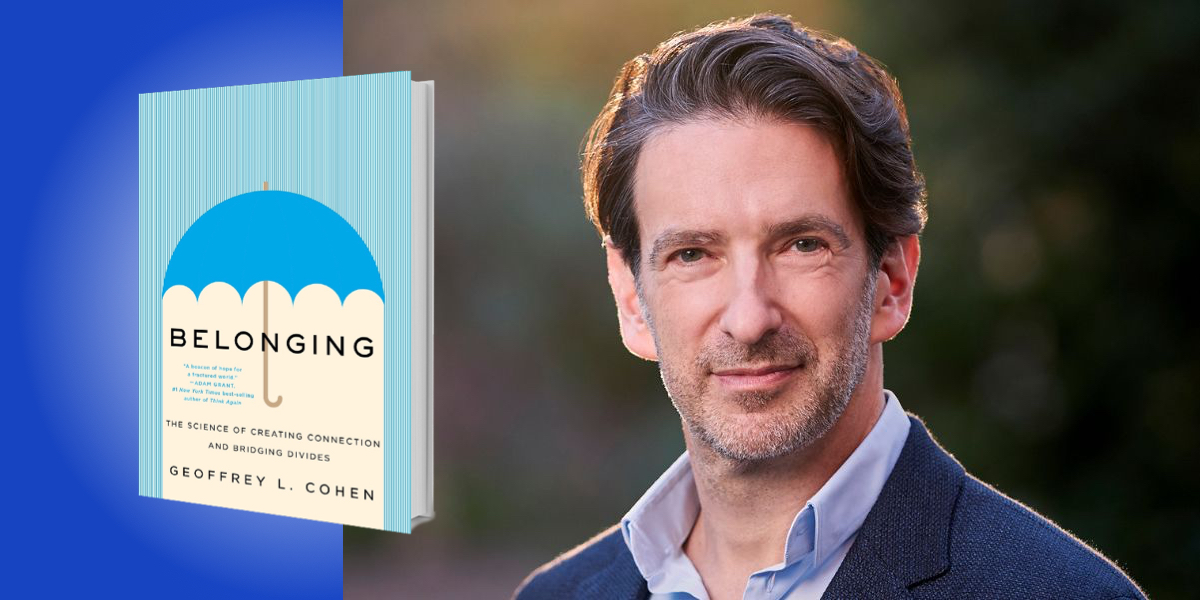

Geoffrey Cohen is professor of psychology and the James G. March Professor of Organizational Studies in Education and Business at Stanford University.

Below, Geoffrey shares 5 key insights from his new book, Belonging: The Science of Creating Connection and Bridging Divides. Listen to the audio version—read by Geoffrey himself—in the Next Big Idea App.

1. A sense of belonging matters.

Belonging matters not just in early development, as psychologists discovered in the mid-20th century. It matters throughout the lifespan, from the cradle to the grave. Of course, your smarts, grit, and passion contribute to your health and fulfillment and even to your success at school or work. Just as important and maybe even more important though is your sense that you belong there, that you feel at home.

In one national study, first-year college students’ numerical rating of agreement with a single statement, “I feel a part of my college,” proved to be one of the strongest predictors of their enrollment in college two years later. A response to a single item predicted retention years later, and it was even more statistically significant than their accumulated high school records.

If a school or workplace is looking to become a place where students or employers stick around, nurturing a sense of belonging may be a really good place to start.

When I was a first-year assistant professor surrounded by esteemed scholars I had previously only read about, I felt acute doubt about whether I belonged in my profession. I’d go whole days ruminating about whether I could cut it or about what other people thought. Little things loomed large. A colleague would ask me a question about my research. I’d feel as if they were tearing me down when that wasn’t the case. I’d come home from work exhausted, even though I’d accomplished almost nothing the whole day except worry. At the same time, small experiences, like a stimulating conversation with a student or even just a thankful email from a colleague re-energized me, gave me confidence, and kept me in the game.

My colleague, Greg Walton, and I did some research showing how seemingly trivial experiences such as these can have big effects. We found that when college students were led to believe, through an experimental ruse, that they happened to share a birthday with a math major, these participants became more motivated in math, and worked harder and longer on a tough math problem.

“A response to a single item predicted retention years later, and it was even more statistically significant than their accumulated high school records.”

An example of how belonging matters in a medical context is demonstrated when Gregory Carter and his colleagues sent postcards to patients who had previously been admitted for attempting suicide. The postcard simply said the hospital staff was thinking of them and wished them well. The postcards reduced the number of suicide re-attempts by half. There is great power to the message you belong.

2. Our sense of belonging is shaped by the lived experiences of our day-to-day lives.

In the Western World, we have a strong bias to think that what really matters in shaping people’s thoughts, feelings, and behavior is the kind of person they are—what’s inside of them. We tend to think that whether you’re a loner, an introvert, an optimist, or a pessimist, predicts your feelings, thoughts, and behavior. While personality matters, it doesn’t matter nearly as much as we think.

Our social situation, our circumstances, and how we see them shape us. Who we are depends on where we are. The situations that we create for one another and for ourselves can generate or undermine connection.

A great example of this is the experiment by Lee Ross and his colleagues. Each participant of the study plays a simple game with another player. There’s a big pot of money. Each player can make one of two moves; either go for the grab and try to take all the money or choose to share the pot with the other player. Most observers, when asked to predict what’s going to affect the player’s move or choice, say it’s their personality—whether they are greedy or a nice person, for example. It turns out that what matters more is a simple aspect of the situation: the name of the game.

When the experimenter offhandedly refers to the contest as the Wall Street game, 70 percent of people go for the grab. If the experimenter calls the same game the community game, 70 percent of players decide to share. Additionally, players who have a reputation as being nice or greedy respond in the same way to the name of the game.

This study is empowering. As we go about our lives as friends, managers, teachers, parents, caregivers, even strangers out in the world, we have some room to maneuver—some latitude to define through words and actions—the situations we inhabit as community games. We can trust and care for one another. In one study by Michael Schwabe, for instance, when political partisans simply expressed their views by saying, “I think,” beforehand, the other side was much more open and interested in what they had to say.

“Who we are depends on where we are.”

Even long and bitter divides can be closed to a surprising degree by giving people new situations that bring them together in a common purpose. Research shows that attempts to ameliorate conflict by changing individuals’ attitudes with persuasion seldom work. What’s the alternative? Give people new situations. The political scientist, Salma Mousa did just this. She created a soccer league in Iraq, a country ravaged by war and genocide. Some of the teams integrated Muslim and Christian players, between whom relations were tense and scarred by distrust. At the end of the season, Mousa found that tensions between the players from the two groups eased considerably, and lasting friendships were formed. The percentage of Muslims and Christians who played together in the off-season more than tripled relative to a control group.

3. As individuals, we each have the power to create belonging out there in the world.

The great truth of social psychology is that the situation is powerful, but the opposite of a great truth is also true. The individual is powerful too. Each of us, as part of the situation we are in, shares some of the power of the situation. By changing the situation through our words and deeds, we can have big effects.

One example comes from a female director of a major Silicon Valley firm. She was about to give a presentation to her stakeholders. It was a make-or-break moment and she was really nervous. She was aware that she was one of a few rising female leaders in the industry at the time, which dialed up her stress and doubts about belonging. As she was about to take the stage, the CEO walked up to her, looked her in the eyes, and said, “You are changing this company.” It was only five words, but they sent the message that she belonged and that she could do it. She nailed the talk.

Educators can create belonging for their students simply with the feedback that they give. Teenage Black students, many of whom often worry about their belonging in school, wrote an essay for their teacher. The teachers then gave each essay written critical feedback pointing out areas of weakness and strategies for improvement. Some of these essays included a handwritten note from the teacher paperclipped to the essay. That note simply said, “I’m giving you this criticism because I have very high expectations and I know that you can reach them.”

For the group of kids who received this note, the percentage of essay revisions and second tries jumped from 17 percent to 71 percent. This message of validation sent these students on a positive course. Years later, findings showed that the note increased the percentage of students who made it to a four-year college by 30 raw percentage points. Teachers can have a powerful influence with a one-sentence note. Similarly, this demonstrates the powerful influence we can all have on people for whom we show support and care.

4. Don’t believe everything you think.

This quip can actually be found on a bumper sticker. It distills so much of the wisdom on bias in social psychology. Just because we think, feel, or even see something does not make it true.

We have an outsized faith in the value of our thoughts, feelings, and perceptions, and we fail to realize that these are often untrustworthy constructions of our own minds. The biases of the mind that psychologists have uncovered—stereotyping, confirmation bias, the tendency to blame individuals rather than situations—are some of the most formidable foes to creating belonging. One way to overcome bias is simply to be aware that we’re capable of doing so. We can also craft situations that keep these biases at bay. You can think of these as protective guardrails in our situations.

Research by Eric Uhlmann found that people, when asked to decide between a male and a female candidate for the job of a police chief, favored the male. What they did was unconsciously shift their criteria to favor whatever credentials the man happened to have. As a result, when participants hired the male candidate for the job, they thought that they had hired the right man for the job, when in fact they had created the right job criteria for the man. A simple situational hack can eliminate gender discrimination: people can commit to their hiring criteria in advance of reviewing job applicants and their credentials.

“We have an outsized faith in the value of our thoughts, feelings, and perceptions, and we fail to realize that these are often untrustworthy constructions of our own minds.”

Although we can’t always trust our minds, by being aware of this fact, we can better craft situations that foil our biases and create inclusive defaults.

5. Get the perspective of another human being by asking questions.

“Perspective-getting” is a term coined by the social psychologist Nick Epley and his colleagues. Rather than try to imagine or take the perspective of another human being, ask questions. When we try to take the perspective of others, even of close friends, we are less accurate than we think. We end up not knowing each other, and not knowing that we don’t know each other. As a result, we don’t get to know each other as much as we could. We don’t establish that authentic basis of connection—being seen and being known for who we are.

The solution is blazingly simple. Ask people good questions and listen to the answers. Perspective-get. Even though it’s simple, it’s very hard to do in the rush of everyday life. We are so overconfident in our ability to read people that we don’t think we need to perspective-get as much as we actually do.

One benefit of perspective-getting is that you convey to people that you are genuinely curious about who they are. This act of curiosity fortifies their sense of belonging, helping people to feel at home and to perform to their full potential.

In one experiment, when middle school teachers took the time over the course of the year to ask teenagers from marginalized communities about their most important values—what they cared for, what brought them joy—the students responded by earning higher grades compared with students in a control group asked about a neutral topic.

When these students felt that they belonged in school, and that they were seen, these students went on to earn better grades over the next two years of middle school. This then set them on a better academic path. Years later, we found to our surprise, that the percentage of students who made it to a four-year college as a result of this exercise in perspective-getting increased by 20 raw percentage points. Perspective-getting can even help to bridge the partisan divide roiling our country.

In the smallest corners of social life, we can look for opportunities to conjure some of the magic of belonging. Community can be found and created in the most unlikely places. We can all change the world in small ways. We can shape situations to make them less threatening and more welcoming, allowing people from all walks of life to feel that they belong and thrive.

To listen to the audio version read by author Geoffrey L. Cohen, download the Next Big Idea App today: