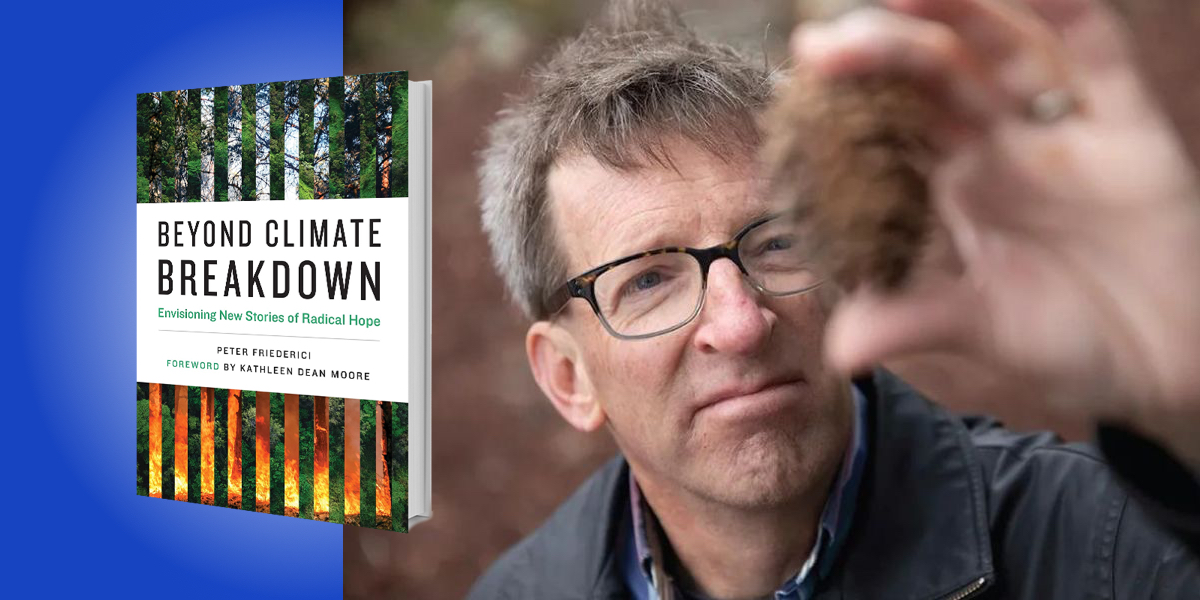

Peter Friederici is a journalist, professor of science communication in the School of Communication and coordinator of the Sustainable Communities Program at Northern Arizona University.

Below, Peter shares 5 key insights from his new book, Beyond Climate Breakdown. Listen to the audio version—read by Peter himself—in the Next Big Idea App.

1. All stories have shapes.

Let’s say two people run into each other on the sidewalk this evening and one blurts out “You’ll never believe what happened today.” Depending on the mood of that person, the other person can pretty quickly figure out what sort of story is coming. Is it tragic like a car crash, a bad medical diagnosis, or someone getting fired? Is it a funny story, maybe even a ridiculous joke? Is it a new social media outrage? These are all different types of stories that demand different responses.

In our everyday lives, we’re really good at picking out the cues that tell us what kind of story is coming. Those cues then determine whether we should respond with a laugh, a sympathetic smile, or a gasp. They tell us how to integrate the new information within our existing worldview.

As good as we are at figuring out the shapes of stories coming from people in our everyday lives, we are remarkably bad at detecting the shape of large-scale narratives shared in a society. It’s because we’re uncritical about the shape of climate breakdown stories, in particular, that progress on what many agree is humankind’s most pressing problem has been so achingly slow.

Look at what some of those stories, or narratives, are: Widely disseminated story frames that rest on shared and often unquestioned assumptions.

2. Climate change narratives are broadly shared.

When we’re faced with a complicated situation, humans have a tendency to reach for pre-packaged stories that can help us understand. We tend to reach for the stories that fit our existing worldview. A limited number of story shapes have characterized mainstream narratives around climate change.

Most notoriously, there’s denial, or a stance that says climate change can’t be happening, or that it isn’t linked to human activities. It says that humans can’t change the Earth’s climate to any significant degree, or that what’s happening now is no different than so-called “natural” climate change that has happened in the past.

“A global survey in 2021 found that more than 45 percent of people 25 and under report that climate anxiety affects their daily functioning.”

An offshoot of this is the religious fundamentalist narrative that says climate change is God’s work. A 2016 poll showed that 14 percent of Americans say that climate change is probably a sign of the Biblical end times, and another 18 percent weren’t sure. That’s a third of the electorate who probably won’t place the climate high on their list of priorities.

Others believe that climate breakdown is an occasion to make money, which is certainly true. Change brings opportunity, even when its overall impact is negative. One version of this storyline that seems promising at face value is so-called “green growth.” Green growth is based on the idea that we can invent and innovate our way to a climate-friendly society without having to make major sacrifices in our way of life. However, the technical and pollution hurdles to this are huge.

A major emerging climate breakdown narrative is proliferating fast, especially among young people. It’s despair—the sinking feeling that humans simply can’t deal with the problem fast enough, or in a big enough way, to assure a livable future. A global survey in 2021 found that more than 45 percent of people 25 and under report that climate anxiety affects their daily functioning.

3. These narratives are all shaped like tragedies.

On the face of it, these narratives seem very different—they even contradict one another. But in a very important way they have a similar structure. They’re all tragedies, in the sense that the ancient Greeks meant when they developed the roots of our Western literary traditions dozens of centuries ago.

What characterizes a tragedy is that the conditions that begin the story can’t be changed later. A classic example is the story of Oedipus, who in his youth hears a prophecy that he will kill his father and marry his mother. He doesn’t want that. So he structures his life to avoid that fate. But what happens? His elaborate efforts themselves make the prophecy come true.

“What characterizes a tragedy is that the conditions that begin the story can’t be changed later.”

In what way are our shared climate change narratives tragic? They all have embedded in them pre-existing conditions, and the assumption that those conditions can’t change. In the case of denial, the assumption is that humans can’t do anything consequential enough to change the global climate. In the case of green growth, the assumption is that the economy has to keep growing no matter what. A number of U.S. presidents have said this very thing about climate change, beginning with George H.W. Bush, who 30 years ago said “the American way of life is not up for negotiations,” before the Earth Summit in Rio. That prevailing attitude hasn’t changed much since.

The despair narrative, too, is tragic, because it assumes that individuals and societies can’t change quickly enough to make a difference. As a result, it implies there’s not much reason to try—that’s a recipe for anxiety, and for giving up.

4. Tragic story frames limit the range of action.

On a planet with finite resources, it seems obvious that a narrative about perpetual economic growth should have become outdated by now. It has, but the narrative itself remains immensely powerful. That’s because of another quality of tragedy that revolves around who gets to make consequential decisions. Who decided that Oedipus would be cursed? Who made the narrative rules? The author of the play, that’s who. In this case, the dramatist Sophocles, who fed off older folktales.

Shared climate change narratives, of course, don’t have a single author. They are shaped and kept alive by a limited number of authors, namely powerful interests in politics, business, and the media. Together, they shape public conceptions of what is economically feasible or, as the phrase goes, “politically possible”, even when those conceptions work counter to our long-term interests.

A great example of this is our economy’s ongoing use of coal, oil, and gas. Executives at the companies that extract them have long known the practice to be highly destructive. They’ve worked really hard to craft the narrative that there’s no good alternative to their use. This narrative is powerful enough that during the 2016 presidential campaign the practice of “rolling coal”, or retrofitting pickup trucks to produce maximum smoky emissions, became a symbol of political support for candidate Donald Trump.

5. Comedy offers alternatives that tragedy can’t.

Even if what we might call “zombie narratives” of tragedy are very powerful, they aren’t all-powerful. The ancient Greeks distrusted the considerable power of the tragic narrative, and developed a countervailing storytelling tradition called comedy. It might offer a way out, even out of the unprecedented situation in which humans now find themselves.

“What comedy always does is adapt, improvise, get through.”

Unlike tragedy with its tight constraints, comedy is highly adaptive. It can deal with new realities because it can improvise. Comedy is the literary form in which the jester can make fun of the king, where men and women dress up as one another, where the lines between humans and animals blur, where established power structures don’t always prevail.

Comedy isn’t always funny, though jokes and laughter are powerful tools for getting through tough situations. What comedy always does is adapt, improvise, get through. In the real world there are lots of examples of comic approaches. One of the best is biological evolution itself, which never says no to any possibilities. In evolution, genetics tries out lots of approaches; some work, some don’t. The overall goal stays the same: the continuation of healthy, diverse life. It’s worked for a long time, even through episodes of mass extinction and other profound changes.

By adopting storytelling approaches that incorporate ideals of comedy, maybe we can develop approaches to climate breakdown that are democratic, adaptive, and less strongly-tied to the inertia of decisions made in the past. Maybe one of the oldest stories, namely the way that life has continuously adapted to deal with new problems, can help guide us into a future of hope, rather than despair.

To listen to the audio version read by author Peter Friederici, download the Next Big Idea App today: