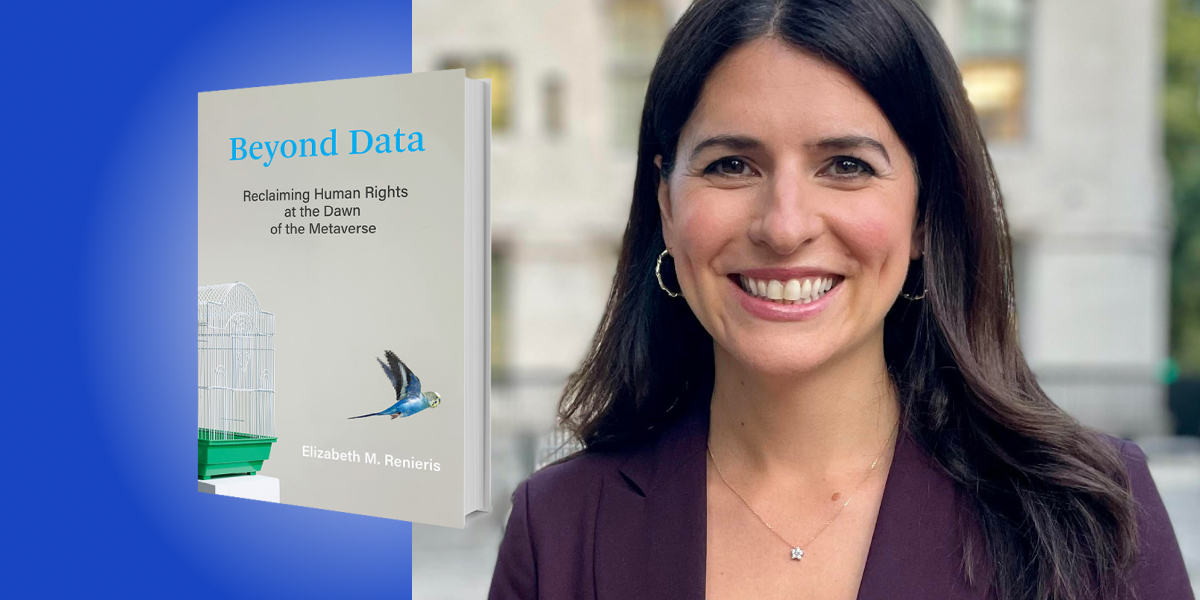

Elizabeth Renieris is Senior Research Associate at the Institute for Ethics in AI at Oxford University. She is also a data protection and privacy lawyer. Her work focuses on the ethical and human rights implications of emerging technologies like artificial intelligence and machine learning, digital identity, and extended reality technologies.

Below, Elizabeth shares 5 key insights from her new book, Beyond Data: Reclaiming Human Rights at the Dawn of the Metaverse. Listen to the audio version—read by Elizabeth herself—in the Next Big Idea App.

1. We are obsessed with control over data.

When we think of privacy today, we may reflect on our lack of it, specifically, in relation to the ways we are tracked and surveilled online through the digital breadcrumbs we leave behind. Companies like Facebook, Google, and Amazon may come to mind, as well as concepts like surveillance capitalism or targeted advertising. We may recount the seemingly endless stream of high-profile data breaches exposing consumer data, health data, financial data, or scandals like Cambridge Analytica. After all, we are said to live in a “data-driven” world powered by “big data,” in which “data is the new oil” and “data is power.” For some, this means that privacy is dead, for others, it means we must “own our data” to reclaim privacy.

Our laws are equally focused on controlling personal data—how it is collected, shared, stored, and otherwise processed. Laws prescribe largely unread notices about how our data is used and seek meaningless, perfunctory consent to process it. Laws require companies to keep our data secure and confidential from third parties while imposing few limits on how they handle it or what they do with it themselves. Landmark regulations like Europe’s General Data Protection Regulation (GDPR), and copycat laws the world over, set out “data subject rights.” These are theoretical rights of individuals to access, correct, erase, and transfer their data from parties who process it. It can prove difficult to exercise in practice, while the U.S. awaits federal privacy legislation. We seem to think that if we could just control our data, we would be safe from technology-related harms and abuses.

2. Privacy is much broader than mere control over data.

Privacy is a much broader and older concept rooted in constitutional and human rights law. In 1948, in the fog of war, the UN General Assembly adopted the Universal Declaration of Human Rights, which declared the right to privacy as a fundamental human right. During the world wars, population censuses, national registration systems, and conscription systems for military service became commonplace in much of the Western world. The trauma of two sequential world wars, and in particular the Nazis’ racially motivated atrocities, helped cement international consensus around human rights and shape the values that informed modern-day notions of privacy.

“Advances in computing and networked technologies in the second half of the 20th century would challenge these traditional notions of privacy.”

As with national constitutions preceding it, international human rights law conceived privacy as delimiting the boundaries of one’s family, home, and correspondence in relation to interference by the state. In other words, privacy was deemed necessary to maintain zones or spheres around the inner or private life of the individual: protect the individual’s physical person, home, and family life; to create boundaries that are foundational to the exercise and enjoyment of other fundamental rights and freedoms; to protect individuals from discrimination and harassment; and ultimately, to defend the individual liberty and autonomy necessary for a fully functioning democracy.

Advances in computing and networked technologies in the second half of the 20th century would challenge these traditional notions of privacy which, before electronic or digital communications, still required physical interference or intrusion. The idea of data protection introduced in response, though derived from the human right to privacy, was much narrower. This is when our approach to technology governance, known as the “ICT turn” in the form of data-based technology governance, or the proliferation of principles, laws, regulations, and policies focused on data.

3. Modern data protection laws are based on an outdated view of the world.

Early data protection laws emerged in the 1970s during the early days of personal computers (PCs). At that time, data about people was collected by known entities and stored in clearly delineated databases in both analog and digital. Its purpose was clearly defined—a world in which it was possible to map personal data flows at scale, and to separate the “online” and “offline” environments. These laws hinged on the idea that with sufficient notice and transparency, individuals could meaningfully control the ways in which their data is accessed, used, shared, and processed, for specific purposes. This original paradigm is still the prevailing approach codified in modern data protection and privacy laws, including the gold standard GDPR.

“It is increasingly impossible to separate ‘online’ and ‘offline’ environments.”

However, that world doesn’t exist anymore. Instead, we live in an increasingly cyber-physical world, in which data constitutes the built environment. Flowing through the vast web of Internet of Things (IoT) devices, sensors, AI and machine learning systems, including deep learning and neural networks, increasingly virtual, augmented, mixed, and extended reality systems, at an unprecedented scale and speed, is a world in which it is increasingly impossible to separate “online” and “offline” environments. Data supply chains have become so complex and convoluted that few companies have a handle on the data they collect, store, or process, or can effectively map their data flows. The idea that any single individual could exert any kind of meaningful control over their data in this environment is pure fantasy, and yet, our laws continue to propagate this view.

4. Privacy has become the handmaiden of tech-related harms and abuses.

This gap between the world we live in today and the one presupposed by data protection laws leaves us vulnerable to a loss of privacy, in its original sense, as well as deception, manipulation, discrimination, harassment, and more. It also allows companies to refashion the right to privacy in their own image—as a technocratic exercise in the confidentiality and security of data.

Until very recently, private actors have relied on largely ignored terms of service and privacy policies, as well as their asymmetrical bargaining power to exploit user data. As these practices are challenged, they are increasingly embracing “privacy-preserving” or “privacy-enhancing technologies.” A wide array of technical means, tools, and approaches to help mitigate data privacy and security risks, such as the risk of revealing sensitive attributes present in a data set. Examples include homomorphic encryption, differential privacy, on-device machine learning, and synthetic data generation.

“Data-centric legal frameworks are easy to circumvent.”

When privacy is reduced to the mere privacy, confidentiality, and security of data, there are virtually no limits to what companies can do or the activities they can undertake, as long as they safeguard and secure any data they process along the way. In practice, this distorted, mathematical, or technocratic notion of privacy has incentivized dominant technology firms to bring more into their own ecosystems, deepen their vertical integration, and use privacy as a shield against competition—therefore, making us more vulnerable to control, manipulation, and exploitation by entities wielding unprecedented power.

Data-centric legal frameworks are easy to circumvent, as demonstrated by the use of synthetic data for purposes that would be otherwise impermissible with the use of personal data. The more that our laws continue to concentrate on requiring companies to protect the privacy and security of data, the more we forget to protect the privacy and security of people. As companies continue to find ways to move beyond data, so too must our approach to governing digital tools and technologies.

5. We need an approach rooted in a broader set of human rights.

As data comes to permeate everything, we are at risk of asking too much, and too little, of data protection. On the one hand, data protection has become a kind of panacea for harms wrought by technology, acting as a kind of broad-sweeping, albeit ineffective, tool for technology governance. It is doing far more than it was ever designed to do, and at the same time, we are demanding too little. Our data-centric approach to technology governance has enabled dominant corporations to effectively reduce the once-potent notion of “privacy” to a technical exercise in ensuring the security and confidentiality of data. In this way, privacy, and the derivative right to data protection, have grown divorced from the human rights framework, and in turn, lost much of their efficacy and power.

There are more than thirty fundamental human rights and freedoms that apply to our human experience, whether at the hands of digital technologies or otherwise. As the “real” and “virtual” worlds continue to blur, eroding neat binaries like “online” and “offline” and as everything becomes infused with data, there will be no such thing as digital or data rights, only rights. So long as technology governance is predicated on data or specific technologies, it will be wielded and shaped by those who control both: namely, powerful commercial interests. Only when technology governance is predicated on human rights, which attach by virtue of our humanity, will it be framed by human interests. In fact, the human rights framework offers us the only truly human-centric, technology-neutral approach, and it is our best chance of moving beyond data.

To listen to the audio version read by author Elizabeth Renieris, download the Next Big Idea App today: