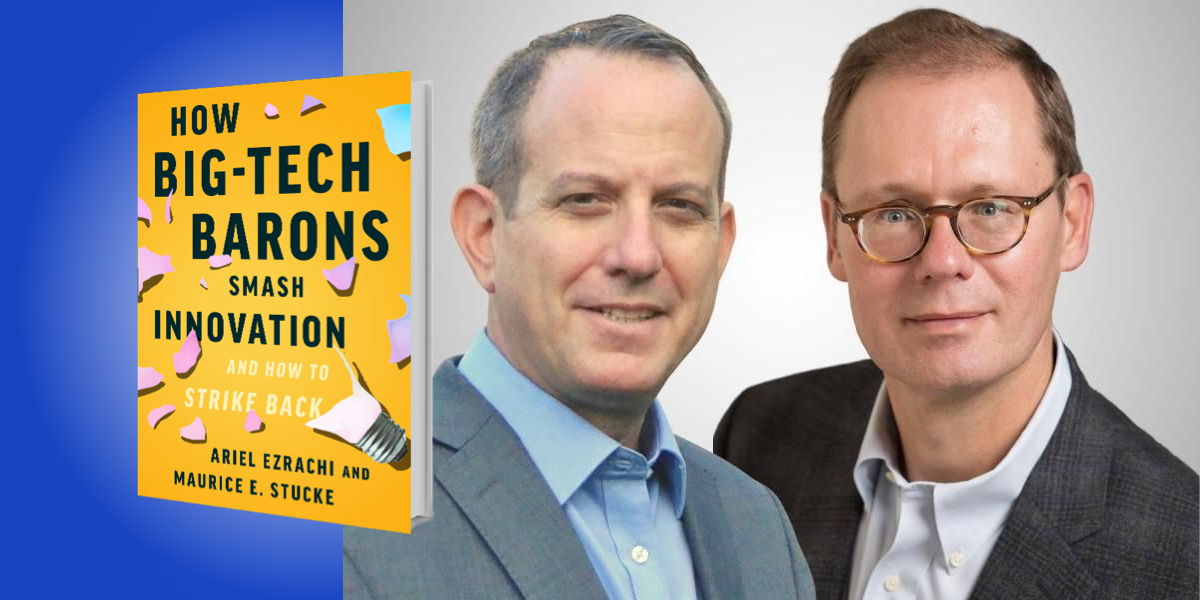

Ariel Ezrachi is the Slaughter and May Professor of Competition Law and a Fellow of Pembroke College, Oxford. Maurice E. Stucke is a co-founder of the Data Competition Institute, a law professor at the University of Tennessee, and of counsel at the Konkurrenz Group.

Below, Ariel and Maurice share 5 key insights from their new book, How Big-Tech Barons Smash Innovation―and How to Strike Back. Listen to the audio version—read by Ariel and Maurice themselves—in the Next Big Idea App.

1. Big-tech barons are not the ultimate innovators.

The narrative we often hear is that big-tech barons are the source and support for innovation and future prosperity. But this is not necessarily true. On paper, the big-tech barons look like innovators. Google, Apple, Facebook, Amazon, and Microsoft invest a lot in research and development. They tout how their platforms help others to innovate by lowering their costs and improving access. But while they certainly put a lot of money into research and development, they also stifle plenty of innovation.

How? They use their vast powers to suppress and distort the flow of disruptive innovation. In other words, while they invest in technologies that support their ecosystem, they also quash any disruptor that threatens their value chain or power. The innovation that we actually receive is geared to allow the tech barons to grow their empire influence. Other innovations that could benefit us may be quashed if they are deemed disruptive to this goal.

This might sound a bit counterintuitive, as we are all accustomed to assuming innovation is synonymous with the digital economy. Five years ago, when the European Commission asked us to study and report on online innovation, we assumed the best. But our study, and the years of research that followed our original report, exposed the astonishing scale of distortion of innovation paths and the adverse effects these have on our society. So while we may applaud the innovations in the latest iPhone, we are actually getting fewer disruptive innovations that could have created significant value.

2. We tend to believe that market forces dictate the path of innovation, but the reality is more like the film The Truman Show.

We generally assume that market forces in the digital economy will deliver the right mix of innovation. This means that if a new technology becomes available or is used by big-tech firms, it is because we, the users, crave it. But the reality is otherwise. Why? Because online platforms control the ecosystem in which users, sellers, and innovators operate. What may seem like a natural dynamic, a natural market in which we interact, is in fact a controlled ecosystem.

“Like Truman in The Truman Show, we may have a sense of autonomy when we choose services online, but we are often traveling a path that was carefully designed for us.”

The tech barons can affect the supply and demand of innovation in these ecosystems. So like Truman in The Truman Show, we may have a sense of autonomy when we choose services online, but we are often traveling a path that was carefully designed for us. Using dark patterns, self-preferencing, and other means, tech barons can direct us toward innovations they want us to adopt and away from disruptors. They can prevent disruptors from entering our universe. They are the ultimate rulers of what we often mistake to be an organic and natural environment.

Consider, for example, the apps that are kicked out of Google and Apple’s apps stores. Why was the privacy app Disconnect kicked out of Google’s Android ecosystem? According to Disconnect, its technology had the potential to protect our privacy and disrupt the money-making machinery of data extraction. In the controlled ecosystem, that disruptive innovation had to be blocked—and blocked it was.

3. Toxic innovation is increasing.

In the digital economy—where innovation is not driven by our desires, but often by the tech barons—it is perhaps little surprise that the nature of innovation changes. And we assume that innovation is a good thing; regulators often posit how they don’t want to chill innovation. But their focus is on how much money goes into research and development, rather than the quality and nature of the innovation.

The truth is that not every innovation creates value. In the digital economy and elsewhere, innovation can also extract or destroy value. So as the big-tech barons become more powerful, the nature of innovation changes. Products and services that were originally meant to help us are now being designed to extract ever more value from us.

“Ultimately, our smart gadgets are not designed for our benefit; they are designed to exploit us.”

Our book looks at the transition of behavioral advertising. Originally, the big-tech barons justified collecting data about us and tracking us across the web by delivering more relevant ads to us. But the technology changed from predicting what we want to better manipulating our behavior and emotions. Some recently registered patents reveal the direction in which many new technologies are heading, including algorithms that can decode your emotions and thoughts.

Ultimately, our smart gadgets are not designed for our benefit; they are designed to exploit us. And those who are most vulnerable to exploitation, the economically and culturally marginal and at-risk segments of our population, will be the ones who suffer the most.

4. What happens online does not stay online.

The toxicity and control over the supply and demand of innovation are not confined to the online world; they affect us even if we seek to avoid the big-tech barons’ ecosystems. We discuss how the toxic innovations to manipulate our behavior are redeployed elsewhere, such as in the political arena. You may have heard of Cambridge Analytica, but this is just one high-profile example of the many that we discuss in the book.

Ultimately, the toxic innovations from the big-tech barons’ ecosystems ripple through society, helping spread conspiracy theories, false news, and hate. When Facebook’s algorithms, for example, rewarded negative stories, political parties became more negative in their messaging. This rancor and tribalism weaken trust and democratic systems. Similarly, the new technologies affect our self-esteem and mental health.

Beyond the political, societal, and human stories lies a technological story, a story of innovation designed to drive profits, irrespective of the effects on democracy, society, and our well-being.

“Toxic innovations from the big-tech barons’ ecosystems ripple through society, helping spread conspiracy theories, false news, and hate.”

5. Duck hunting, cities, and the future of innovation.

You might think that Europe’s new regulations, such as the Digital Markets Act, Digital Services Act, and Data Act, as well as the proposed legislation in the United States and the many lawsuits against the big-tech barons across the globe, would restore competition and innovation. But it is essential to ask: are we aiming at the right target? When you hunt ducks, you can’t shoot where the duck was. Instead, you must aim where the duck is heading.

The problem with many of the proposed antitrust policy reforms is that they target many of the big-tech barons’ past anti-competitive practices. But in the digital economy, the big-tech barons need not resort to these same past practices once they are powerful. So the proposed regulations focus on past anti-competitive strategies. They follow the curve rather than aim where the tech barons are heading.

But it’s not simply about reining in the tech barons. At a more fundamental level, how can we promote innovation in the digital economy, innovation that actually creates value? One surprising answer is cities. We often think about investing in companies to support innovation, and as companies increase in size, they continue to innovate—but at a slower rate. Double the size of a company, and you won’t necessarily double the number of patents. But with cities, as they increase in size, they generally foster more innovation. Double a city’s population, and you will more than likely double the number of patents from that city. So policymakers, rather than subsidizing firms to innovate, could do more to support cities. Cities, rather than large corporations, should be treated as the engine for diversity and growth.

In conclusion, instead of improving our standard of living, technological advances may prolong or worsen wealth inequality, reduce our autonomy and well-being, and destabilize democracies. And we can’t expect this trajectory to self-correct; we need to fundamentally overhaul our policies. We can and should expect more—but only if we demand it.

To listen to the audio version read by co-authors Ariel Ezrachi and Maurice E. Stucke, download the Next Big Idea App today: