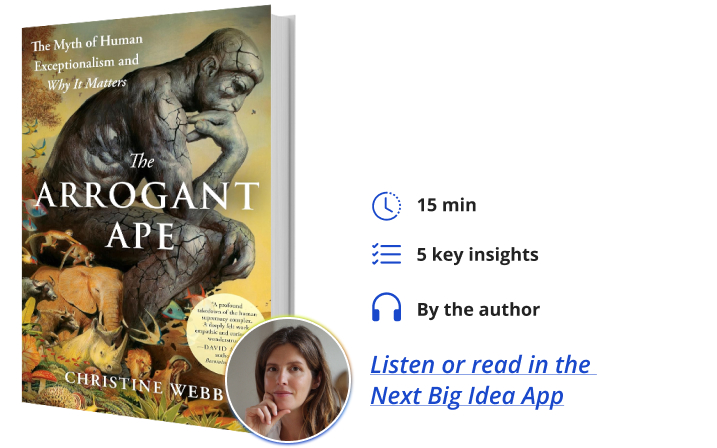

Dr. Christine Webb is a primatologist studying the social and emotional lives of our closest living relatives. She is an assistant professor in the Department of Environmental Studies at New York University, where she is part of the Animal Studies program. Her work has been covered by the New York Times, The Washington Post, National Geographic, and the BBC.

What’s the big idea?

The Arrogant Ape explores how human exceptionalism has distorted our science, our ethics, and our relationship with the natural world. This dominant cultural narrative of our superiority over Nature has fueled the most serious crises of our time. To remedy our wrongs, we need to internalize a humbler worldview that rethinks our place in the rich tapestry of life and intelligence found on this planet.

Below, Christine shares five key insights from her new book, The Arrogant Ape: The Myth of Human Exceptionalism and Why It Matters. Listen to the audio version—read by Christine herself—below, or in the Next Big Idea App.

1. The most dangerous animal is the one that forgot it’s an animal.

We often treat “human” and “animal” as fundamentally different. That’s inaccurate and dangerous. Human exceptionalism—the belief that we are fundamentally separate from and superior to other forms of life—has justified exploitation of the natural world. That mindset is fueling the crises we face today: wildfires, rising seas, mass extinctions, and global pandemics.

When discussing the environmental crisis, we typically focus on its visible causes: fossil fuels, industrialized farming, and habitat destruction. But we rarely examine the worldview that makes such systems possible in the first place—a story in which the Earth is made of objects and resources for our exclusive use. It tells us we are rational and cultural, while other species are merely instinctive and mechanical. That we alone think, feel, and matter in complex ways and that, because of this, we are the rightful masters and owners of Nature. This belief in human exceptionalism justifies not only the exploitation of other animals and ecosystems, but also the exploitation of other human beings. It shapes everything from economics and politics to language, education, media, technology, and even science.

But unlike the visible causes of the ecological crisis, we rarely stop to question human exceptionalism. Not necessarily because it’s hidden, but because this belief is almost never explicitly named, taught, or scrutinized. It functions as an unspoken assumption that shapes the behavior of individuals, corporations, and governments alike. It’s from this invisibility—this implicit sense that humans are “obviously” superior—that human exceptionalism draws its power. I think it’s the most powerful unspoken belief of our time.

To survive the crises we’ve created, we don’t just need greener economies, technologies, and politics. We need a different relationship to the living world, and thus we need new stories that reconnect us to that world and remind us that we are fundamentally animals after all.

2. Human exceptionalism isn’t in our DNA.

Many people intuitively think that human exceptionalism is part of our nature. Humans around the world tend to care about and value human life more than nonhuman life. But recent studies in cross-cultural and developmental psychology are challenging these assumptions. They instead show that human exceptionalism is highly culturally dependent and that children do not exhibit such a human-centric bias.

In one 2021 study, researchers explored whether human exceptionalist attitudes develop with age. They asked American children and adults whether they would choose to save the lives of humans over other animals (like dogs or pigs). Whereas most adults chose to save one human over 100 dogs or pigs, children lacked this pro-human bias and chose to save ten pigs over one human. These findings contradict the view held by many philosophers and psychologists that children begin reasoning from a human-centric vantage point, with an initially narrow “moral circle” that gradually widens over development.

“Human exceptionalism is not a universal truth.”

Instead, studies like this suggest that the perspective that humans are morally special is a socially acquired ideology. This worldview likely emerges as children become more active participants in society and learn to internalize the many ways other species are consumed, commodified, and framed as lesser, a society that constantly reminds us that humans come first.

Cross-cultural research backs this up. In American urban centers like Boston, people tend to reason about nature by analogy to humans. But in rural Yucatec Maya communities in Mexico, where people live in close connection with plants and animals, people don’t show that same human-centered bias.

Human exceptionalism is not a universal truth. It’s a worldview passed down by the dominant Western culture. Not something built into our biology, but something shaped by our experience. And if it can be learned, it can also be unlearned.

3. Intelligence isn’t a ladder.

We’re often told that intelligence evolved like a ladder, and we humans sit proudly at the top. But that story is misleading.

For one, most research on animal cognition is stacked against other species from the start. In my own field of primatology, we often compare the intelligence of captive chimpanzees—raised in highly restricted man-made environments like labs or zoos—with that of fully autonomous Western humans. And then we act surprised when they don’t “measure up.”

And we still tend to use human intelligence as the benchmark. We test animals based on how well they mimic our behaviors, senses, and norms. We prioritize vision over smell, even though a dog’s nose can read the world in ways our eyes never could. We elevate hands and fingers that can point, ignoring the intricate work done by trunks, beaks, and fins. We privilege verbal reasoning and human language, overlooking the complex communicative and indeed linguistic abilities of other species. Instead of asking how other forms of life think, we continue to ask how well they think like us. We assume the human brain is the blueprint for all minds, and anything that deviates from it is inferior. Even beings without brains at all—like slime molds or fungi—are often written off as mindless, no matter how complex their behaviors.

We were taught that cognition evolved in a neat, linear sequence: bacteria, plants, worms, lizards, monkeys, apes… us. This idea is even baked into the name Carl Linnaeus gave to our taxonomic order: Primates, from Primata, meaning “of the first rank.”

“Uniqueness isn’t the same as superiority.”

But intelligence doesn’t work like that. Evolution doesn’t produce a ladder. It produces diversity. Minds evolve to solve different problems in different environments. And almost every trait once claimed to be uniquely human—tool-use, language, culture, memory, self-awareness, empathy, morality—we’ve now found elsewhere. Not just in other animals, but increasingly in plants, fungi, and other life forms.

That doesn’t mean humans aren’t unique. All species are unique. But uniqueness isn’t the same as superiority. So rather than a ladder, think of intelligence like an ecosystem that is full of specialized minds shaped by different needs and niches. The human brain is just one adaptation among many. Reducing other species to lower ranks in a hierarchy narrows our view of life and of our place within it.

4. Nature isn’t purely competition—it’s a community.

When you first learned about evolution, what phrases stuck with you? Probably “survival of the fittest” or “struggle for existence.” These phrases shape how we see nature—as competitive, brutal, and hierarchical—and in turn how we see ourselves—as the inevitable winners of this evolutionary contest. But that vision is deeply outdated.

Modern biology tells a story of interdependence, not dominance. Your body is an ecosystem of microbes, which outnumber your human cells 10 to one. Forests thrive through underground fungal networks that connect and nourish trees. Even some of evolution’s biggest success stories (like mosses, who have existed for hundreds of millions of years) succeed not by outcompeting others, but by quietly making life possible for those around them.

Darwin himself understood this. In On the Origin of Species, he explains that he uses the term “struggle for existence” in a large and metaphorical sense to include the dependence of one being on another. Evolution is not solely a tale of competition; it’s equally a story of cooperation. I’ve seen this firsthand in the chimpanzees I work with. The most competitive contexts, like conflicts, often require cooperative solutions, such as reassurance and consolation behaviors. Entering cooperative relationships allows individuals to outcompete others. Life, and community, in all their forms, depend on managing both cooperative and competitive relationships.

“Evolution is not solely a tale of competition; it’s equally a story of cooperation.”

And yet, our cultural obsession with competition still distorts how we interpret evolution. We frame human ascendancy over the natural world as some logical, inevitable consequence of the natural selection that came from humans acting in their own self-interest. Not only does this get evolution wrong, but it also overlooks marked cultural diversity in how humans relate to nature. Many human societies have lived in relative balance with their environments. Animist, pagan, and Indigenous cultures have long recognized the interdependence and kinship between humans and other forms of life—something that governing Western traditions have often failed to see.

Fortunately, this is beginning to change. As Western scientists increasingly partner with Indigenous communities, we’re witnessing a more relational approach to knowledge in practice—one that’s reviving endangered species, restoring habitats, and expanding what counts as legitimate knowledge. This is about expanding science and recognizing that the most cutting-edge science today is, in many ways, catching up to ancient understandings of relationality.

5. Humility matters more than ever.

The coronavirus pandemic offered a sobering reminder. Nature seemed to be defying the primacy of humans like never before. And yet, the headlines mostly celebrated human ingenuity, like our scientific brilliance in creating vaccines. Far less attention was paid to how our relentless exploitation of animal habitats may have triggered the virus in the first place and how it’s likely to trigger the next one.

At the same time, militarized discourses of a “war” or “fight against” the virus perpetuate the view that Nature is a force to be controlled and dominated. Such human-centered narratives also figure in recent discussions about climate change and environmental “technofixes” like solar geoengineering and the colonization of Mars. These framings bypass a critical opportunity to deconstruct forms of human exceptionalism in the public imagination. The narrative of human mastery over Nature got us into this mess, and it would be wise to recognize that we can no longer rely on the values, institutions, and scientific methods that gave rise to this moment. We need a radically humbler approach.

We rarely consider arrogance to be more than a personal flaw. But what if it’s also a civilizational one? Philosophers have argued that arrogance is a vice because it limits our capacity for meaningful relationships and self-understanding. Without mutual respect, friendships become shallow, and without genuine relationships, we lose a mirror into our own character. While philosophers focus on human-to-human relationships, their logic extends to our relationship with other forms of life. The ideology of human exceptionalism limits our ability to understand ourselves.

“Humility may be our most vital resource.”

So, what does it mean to be human? The word human has a forgotten origin. It comes from humus, the rich soil of the earth. To be human is to be of the earth. Not above it. Not outside it. So why do we insist otherwise? Perhaps, like the person who boasts too loudly, we are overcompensating. Arrogance often masks deeper insecurities. Civilizational superiority may be no different.

My friend, the cultural ecologist David Abram, points out that the word humility shares the same root as human and humus. For our ancestors, to be truly human meant to walk humbly on the earth. Psychological studies show that humility improves relationships, increases well-being, and even boosts resilience. And while psychologists have mostly studied these effects in human relationships, why stop there? What if we extended that humility to the more-than-human world?

In the face of environmental collapse, humility may be our most vital resource. It fosters better relationships. It builds resilience. It inspires wonder. It might just help us navigate what we’ve set in motion and help us become, once again, human in the truest sense.

Enjoy our full library of Book Bites—read by the authors!—in the Next Big Idea App: