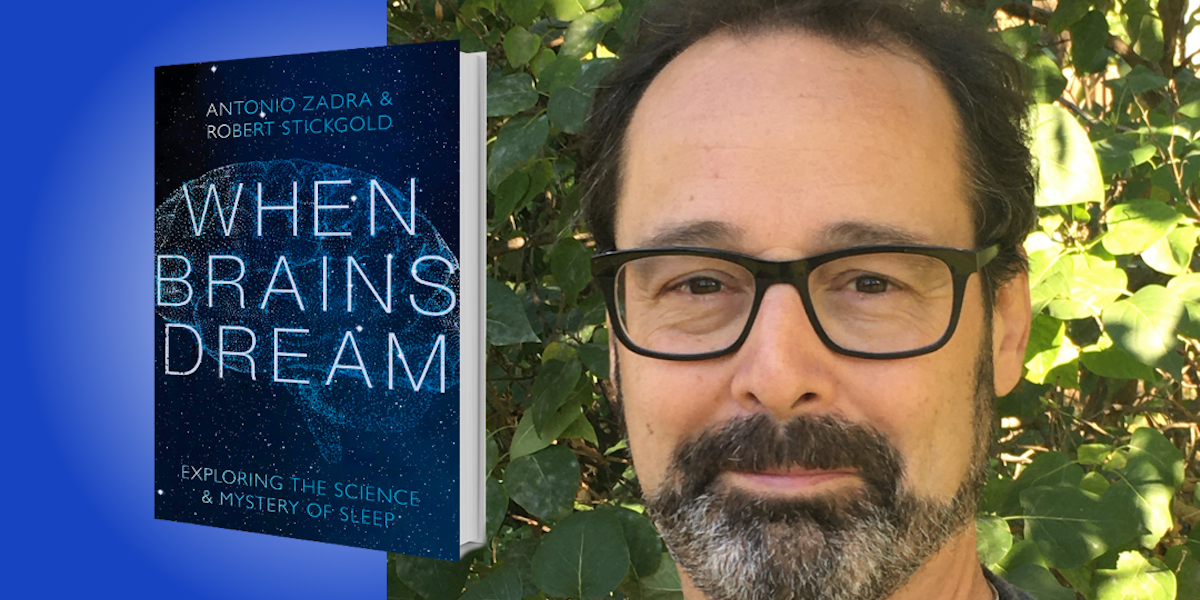

Antonio Zadra is a professor at the University of Montreal and a researcher at the Center for Advanced Research in Sleep Medicine. He has appeared on PBS’s Nova and BBC’s Horizon. Robert Stickgold is a professor at Harvard Medical School and director of the Center for Sleep and Cognition. His writing has appeared in Scientific American and Newsweek.

Below, Antonio shares 5 key insights from their new book, When Brains Dream: Exploring the Science and Mystery of Sleep. Download the Next Big Idea App to enjoy more audio “Book Bites,” plus Ideas of the Day, ad-free podcast episodes, and more.

1. Both as a concept and experience, dreams are much trickier than most people imagine.

By now, we are all so familiar with the idea of dreaming that we forget what a strange concept it is. Most preschoolers, for instance, believe that dreams are real—that they originate from outside the dreamer, and that they can be seen by others. It isn’t until the ages of six to eight that most children grasp the idea that dreams are not only imaginary, but that they can’t be observed by others nearby.

Moreover, people sometimes confuse dreams with waking events. “False awakenings”—in which people dream that they have woken up, often in their usual sleep environment—can happen to anyone. In these dreams within dreams, people may “wake up,” get out of bed, shower, and be about to fix themselves breakfast when, to their astonishment, they wake up again. As English physician Havelock Ellis once said, “Dreams are real as long as they last. Can we say more of life?”

2. Dream research was being done long before Freud showed up.

One early pioneer was Alfred Maury, who, in his 1861 book Sleep and Dreams, argued that our dream experiences were directly tied to how different regions of the brain function during sleep. He also correctly concluded not only that our senses could transmit information to the brain during sleep, but also that the sleeping brain could use that information to create a relevant dream.

“Dreams are real as long as they last. Can we say more of life?”

Most people today associate the idea of symbolism in dreams with Freud’s The Interpretation of Dreams. But the first psychologically sophisticated discussion of dream symbols was published almost 40 years earlier by Karl Scherner. Then there was Mary Whiton Calkins, a pioneering female psychologist who was one of the first researchers to use statistical principles to analyze the content of carefully collected dream reports. She showed, for example, that while most dreams occur during morning sleep, dreaming also takes place during earlier parts of the night.

3. Your brain needs to sleep.

For every two hours you spend awake, taking in new information, your brain needs about an hour of sleep, with no information coming in, to figure out what it means. Your brain is working at full speed all night long—every new memory that you formed during the day gets reprocessed while you sleep. How does sleep change our memories? In the simplest cases, it just stabilizes them, making them resistant to interference and forgetting. It also strengthens skills that we’ve learned, like how to ride a bicycle, so we’re better at them the next day.

While sleeping, your brain also extracts patterns from information that came in during the day. It can even solve a puzzle that you couldn’t figure out the day before! So when you wake up each morning, you literally have a better understanding of how the world works than you had when you went to bed the night before. While parts of our brain are carrying out all this crucial memory processing, other parts are dreaming, as we actually dream for most of the night.

“When you wake up each morning, you literally have a better understanding of how the world works than you had when you went to bed the night before.”

4. Dreaming serves an important biological function.

Unlike those non-conscious brain mechanisms that strengthen and integrate the memories from our day, dreaming looks at these new memories and asks, “What do they mean?” That meaning is defined for each of us by the associations our brain makes with a given memory, connecting it to older memories. We call this process NEXTUP, which stands for Network Exploration to Understand Possibilities. The dreaming brain explores neural networks to find useful ideas that could be relevant to an issue at hand. To decide which connections are worth strengthening, the brain needs to dream. It weaves these associated concepts into a story that plays out over time, one where you, the dreamer, have the lead role—and it watches you react emotionally to the ongoing plot. It’s your feelings in the dream that are critical; the brain’s rule seems to be that if the story woven from this new association evokes an emotional response in the dreaming “you,” then it’s worth keeping. The only way your brain can play out such narratives, whether you’re awake or asleep, is to imagine them. In fact, that might be one of the main functions of consciousness—to allow our brain to imagine possible actions and evaluate their value.

5. Much like art, dreams can hold multiple meanings.

Once you’ve recorded a dream that you want to explore, ask yourself some questions to explore what the dream may mean for you. For example, how did you feel in the dream? When was the first or most recent time you felt this way? Think of the dream setting—what was it like being there? Think of the people in your dream—what were they doing? If you recognize a dream character from waking life, what are they usually like? Who or what else do they remind you of? What were the main images in the dream, and what associations come to mind when you think about these images now? It’s also important to remember that new insights about yourself may not arise from the dream as a whole, but rather from a specific element within it. In other words, don’t expect to understand your dreams in their entirety; gleaning information from a central image, theme, or interaction is a much more likely and equally valuable outcome.

For more Book Bites, download the Next Big Idea App today: