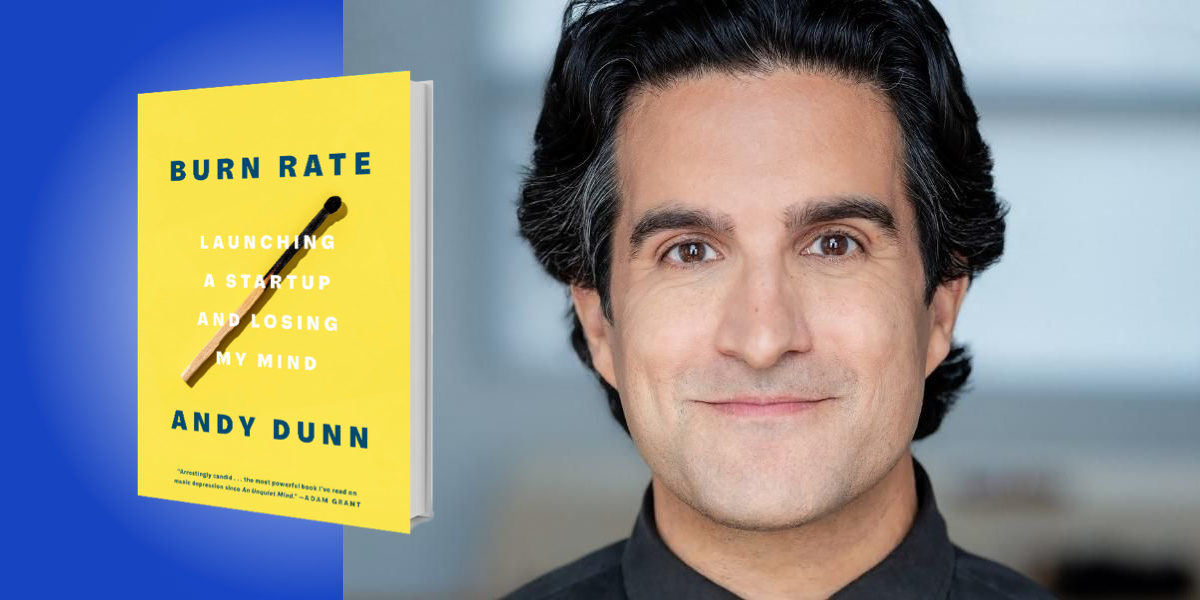

Named to Fortune’s 40 Under 40 list in 2018, Andy Dunn co-founded the ecommerce-driven menswear brand Bonobos in 2007, and served as CEO through its 2017 acquisition by Walmart. As an angel investor and through his venture capital firm, Red Swan, Dunn has backed more than eighty startups, including Warby Parker, Oscar, and Coinbase. Dunn serves on the boards of Monica + Andy, an organic baby-apparel company founded by his sister, and the tech nonprofit Raised By Us.

Below, Andy shares 5 key insights from his new book, Burn Rate: Launching a Startup and Losing My Mind. Listen to the audio version—read by Andy himself—in the Next Big Idea App.

1. It’s important to normalize mental illness in the workplace—and in society at large.

When I was 20 years old, I received a diagnosis for bipolar disorder type I. I spent the better part of two decades in denial of that illness.

The consequences of my denial were profound. Sixteen years after my first manic episode, I experienced a second episode, and I spent a week in the psychiatric ward of Bellevue. Upon release, I was discharged in handcuffs, and charged with felony and misdemeanor assault of my now-wife and now-mother-in-law. Burn Rate details my path back to health. As I reflect on the journey, I wish I had gotten the opinions of people who didn’t tell me what I wanted to hear, but what I needed to hear.

2. The power of vulnerable disclosure.

It’s a funny thing. We assume that what we hold most vulnerable is something that we need to protect, that we need to not share with other people. But the truth is that what is most connecting for others to hear is the thing that is most vulnerable for us to share.

“The only way for us to expunge our shame as a society around issues of mental health is to recognize that there is power in vulnerable disclosure.”

I’m learning this lesson in real time. Previously, the story that I was sharing was one of entrepreneurial success. As much as people want to learn about your success, they’re far more interested in the challenges that you’ve faced—because we all face challenges, and we tend to hide them.

Mental illness in particular leaves no family untouched. The number of emails and direct messages that I’m receiving is an affirmation that we need to do more societally to talk about the issues that we collectively face. As I wrote Burn Rate, and gave harrowing details of my experiences with mania, messianic delusions, psychosis, and suicidal ideation, there were moments when I felt profound embarrassment, humiliation, all the emotions that keep us from sharing. I had to remind myself that the unspeakability is, in fact, what drives the shame. So the only way for us to expunge our shame as a society around issues of mental health is to recognize that there is power in vulnerable disclosure.

3. The power of accountability.

Part of my book oscillates around a problematic relationship that I had with the co-founder of the startup that I was building, Bonobos. When the co-founder divorce was going down in 2009, the narrative that I held was that my co-founder was the root of all the problems. I had externalized blame for much of the dysfunction in our partnership on him. It was only years later—as I had falling-outs with other Bonobos executives, and as I struggled to find a romantic partner—that I came to a difficult conclusion: I’m the problem in my life story.

“Over time, I came to realize that I was the problem.”

And it was upon my co-founder’s departure that I realized that there was no one left to blame except myself. This is a difficult thing to take on psychologically, the idea that we are our own worst enemy. But if we can, and if we can take a step back and evaluate why, there’s actually enormous agency in doing so—which is what gives us the power to change it.

My journey with entrepreneurship is also mirrored in life, where over time I came to realize that I was the problem in my relationship with my then-girlfriend, Manuela. As I began to look more closely at my own issues and change myself, our relationship thrived—and remarkably, she ended up deciding to marry me.

4. The power of candor in communication.

I detail three different family traditions that I belong to. On my dad’s side of the family, who are Scandinavians from the Midwest, there is no confrontation—so eventually, there is no conversation. Small issues become medium-size issues, medium-size issues become big issues, and eventually, no one talks at all. Tragically, my dad speaks to neither of his living siblings.

On my mom’s side of the family, who are Punjabi Indian immigrants, you say exactly what you think in real time to everyone—except the person that you think it about. The result is a nearly perfect exchange of information maximizing harmony, but without the kind of interpersonal growth that comes from a real, face-to-face exchange of information, thoughts, and feelings.

“A family that is willing to be confrontational with one another might actually be a family that is coming together rather than falling apart.”

That’s where my wife’s family comes into play: Brazilian Jews and New York City Jews. The first time I ever had dinner with my now-wife and mother-in-law, my wife was crying. I went to the bathroom; my Scandinavian Midwestern side was dry heaving, thinking, I can’t be a part of this family. I thought she was crying because they were having an argument. But I’ve since learned that they were just having a discussion, and that a family that is willing to be confrontational with one another might actually be a family that is coming together rather than falling apart.

5. In our flaws we find the opportunity for redemption.

Upon discharge from Bellevue, when I was arrested and charged with felony and misdemeanor assault, I felt a level of shame I had never known. It was ten times the shame I had felt from the diagnosis, because I’d been violent. Working through that over time created an enormous amount of guilt—guilt that I had been unwilling to face 16 years earlier when I first received the diagnosis. I hadn’t gotten treatment. I hadn’t been in therapy. I hadn’t taken medication. And the result was that others had to bear the consequences of my failure to take care of myself. No one more so than my now-wife, who was a victim of the violence that night.

On the one hand, the takeaway from that would be to fall into a crippling depression and withdraw from the relationship—and I did one of those two things. The depression was awful, and it took quite a bit of time to get healthy. But I didn’t withdraw from the relationship, and luckily for me, neither did she. Through the relationship therapy we did, the therapy that I did, and all the mutual work, we were able to build what is now a wonderful partnership. Something that could have broken our relationship actually made it stronger—and enables it to endure.

To listen to the audio version read by author Andy Dunn, download the Next Big Idea App today: