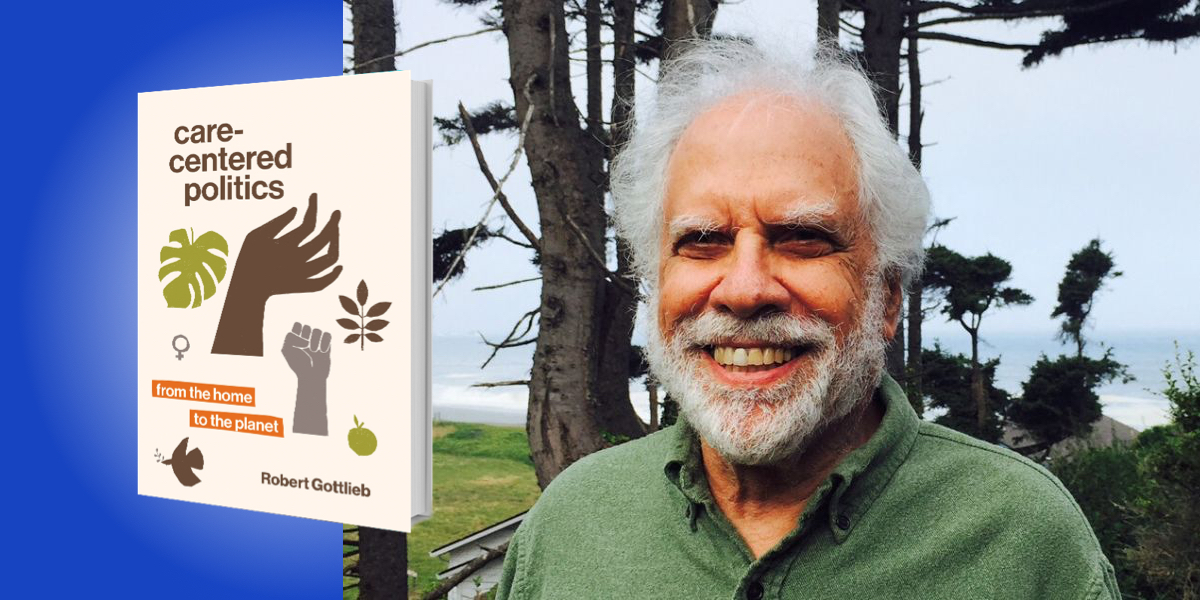

Robert Gottlieb is Professor Emeritus of Urban and Environmental Policy and the Founder and former Director of the Urban & Environmental Policy Institute at Occidental College. He is the co-author of Food Justice and Global Cities, among other titles.

Below, Robert shares 5 key insights from his new book, Care-Centered Politics: From the Home to the Planet. Listen to the audio version—read by Robert himself—in the Next Big Idea App.

1. Care politics is central to care.

Crucial dimensions of care include an ethic, a practice, an economy, and a form of labor—and care politics is important to all of them. Care politics responds to specific needs. It supports child care tax credits, paid family leave for women and men, living wages for care workers, resources for community schools, and for many daily life needs. It advocates for Medicare for All, a universal basic income, reduced work hours, and for a restructuring of work as activity rather than for its market function. It supports, yet also seeks to reorient and expand, the goals of a Green New Deal along care economy lines. And it asserts the right to food, health, housing, and a living planet.

Care politics fosters public policies, community action, and individual efforts for solidarity, mutual aid, interdependence, equality in resources and livelihood, and social and environmental justice. It includes such struggles as the fight against privatization of water in developing countries and promotes public institutions like libraries, those “palaces for the people,” in sociologist Eric Klinenberg’s felicitous phrase.

Care-centered politics can empower people to hope, act, and make change possible. Hope can provide the basis for action, so necessary during a climate crisis and a continuing pandemic that has led to anxiety, despair, and paralysis in action. The late, great Welsh literary critic Raymond Williams put it best: “To be truly radical is to make hope possible, rather than despair convincing.” Care-centered politics is a truly radical idea.

2. Everyone experiences care.

The common wisdom is that everyone receives care or provides care at some point, or knows of others who require or provide care. Care is about life-giving activities and well-being. Yet the support and benefits for who provides and who receives care are not made fairly and equally. Care has not received the political and institutional support it needs. This is despite its universal nature and central role in daily life.

“While care experiences are ubiquitous, care-centered politics is often treated as marginal by policymakers, including those who proclaim a right to life.”

While care has received more attention in recent political debates, it has not been translated into substantial policy change, nor has it led to a shift in behavior in the home or workplace. The care workforce is the fastest-growing segment of the labor market. Care workers are essential workers, and yet most of them are poorly paid, receive little or no benefits, and are not recognized for their life-affirming work. Many are women of color and immigrants.

While care experiences are ubiquitous, care-centered politics is often treated as marginal by policymakers, including those who proclaim a right to life. However, it is also beginning to be identified as the heart of a progressive politics to emphasize the importance of life-affirming activities such as child care, elder care, and care for the planet, as well as highlighting the importance of those who perform the care. “Care is everywhere, all around us,” Ai-jen Poo, a leading care politics advocate asserts. It seeks to promote a “caring with” philosophy, as care theorist Joan Tronto puts it. Care-centered politics can become the cornerstone of democratic politics.

3. The need for a care economy.

A care economy can challenge the hypergrowth and unbounded consumption model of the contemporary capitalist economy. A care economy proposes the goals of sufficiency and equality as the measure of an economy associated with well-being.

A care economy approach is critical of the use of Gross Domestic Product indicators to measure the state and health of an economy. GDP represents the market value of all goods and services but leaves out many care-related indicators of well-being. This includes non-paid care work, whether by family or by individual care-givers, who constitute a huge uncounted part of the labor force—an invisible domain in GDP calculations. Yet non-paid care work for children, elders, and those in ill health, or for housework or nurturing, are essential components of daily life.

A care economy approach seeks to prevent emissions or other forms of pollution, which is essential for local and planetary health. They are also crucial well-being indicators. However, in the dominant market economy, prevention and mitigation actions are considered an economic burden for sectors like the fossil fuel industry, which are GDP mainstays.

“A care economy proposes the goals of sufficiency and equality as the measure of an economy associated with well-being.”

The Care Economy further challenges the privatization and marketization of services as well as the link between hypergrowth and its dependence on unbounded consumption. The Care Economy sees this economic model as one that heightens inequalities and endangers the planet. The care economy approach that promotes sufficiency (knowing what is enough) and equality (enough for everyone) links the economy to well-being rather than growth.

4. Care for Earth.

Care for Earth includes soil health and an ethic of care in relation to growing food and what we eat. Care for Earth was among the principles put forth at the 1991 First National People of Color Environmental Leadership Summit. The Summit declared that the Earth is sacred and requires land and resource use “in the interest of a sustainable planet for humans and other living things.” Care for the Earth has also been a key component of the struggles around food sovereignty. In the Six Pillars of Food Sovereignty declaration in 2007, the participating groups argued that practices such as agroecology and regenerative agriculture, as well as opposition to fossil fuel development and toxic mining, were essential “to heal the planet so that the planet may heal us.”

Gardening is an example of care’s healing activity. “Inch by inch, row by row, gonna make this garden grow,” Arlo Guthrie sings, a mantra during the early months of the pandemic. Gardening can become a type of horticultural therapy. Community gardens, gardens in the home, gardens in schools and prisons, have long been associated with care for the Earth as well as for well-being. Gardens as social activities foster interdependence and connectedness, a “reconnection with earth and community,” as the wise and revered thinker, writer, and activist Grace Lee Boggs had argued. “You can bemoan your fate, or you can plant gardens as the African-American elders taught,” Boggs wrote in the aftermath of the 2008 Great Recession that decimated Detroit and many other places where lands and houses had become abandoned.

5. Reparations and redistribution.

The care politics argument for reparations is an argument about historical reckoning, a type of healing, and a transformative politics of redistribution. Reparations are an important, though controversial concept, particularly for those who dismiss the need for a historical reckoning and compensation for those who have been disadvantaged by historical legacies. Many critics of reparations insist it is too difficult to account for the practices of the past. Yet the irony is that reparations have long been a tool in reverse—paying the slaveholders, or seizing the lands of indigenous people, or compensating the climate emitters. This has happened worldwide, whether the French slaveholders in Haiti, slave masters in the U.S. or UK, the genocide against indigenous peoples, or the multinational fossil fuel and mining companies when they abandon their properties while denying that they have contributed to a contamination of the land and the water. This anti-care reverse reparations history has been the rule, not the exception.

“Care politics is about a peaceful, hopeful, and life-affirming politics when hope sometimes seems out of reach.”

Care-centered politics highlights how a reparations approach speaks to the need to care and repair for the victims of slavery, Jim Crow, racism, class, sex, and gender injustices and exploitation, or for all those who are experiencing or will experience the heat waves, flooding, droughts, fires, and displacements from the climate crisis. It also speaks to the perpetrators and the descendants of those who did the victimizing, to enable them to come to terms with a past that needs reckoning or a present—and a future—that needs repairing.

Care-centered politics requires redistribution to make whole what has been lost or damaged, whether intergenerational wealth or a planet under siege. It is an essential strategy to heal the land and support those displaced. Care politics is about a peaceful, hopeful, and life-affirming politics when hope sometimes seems out of reach. It is about children, elders, essential workers, immigrants, refugees, and the abandoned. It is about caring together and caring with. It is about everyday life and the need for cooperation, sharing, and solidarity.

To listen to the audio version read by author Robert Gottlieb, download the Next Big Idea App today: