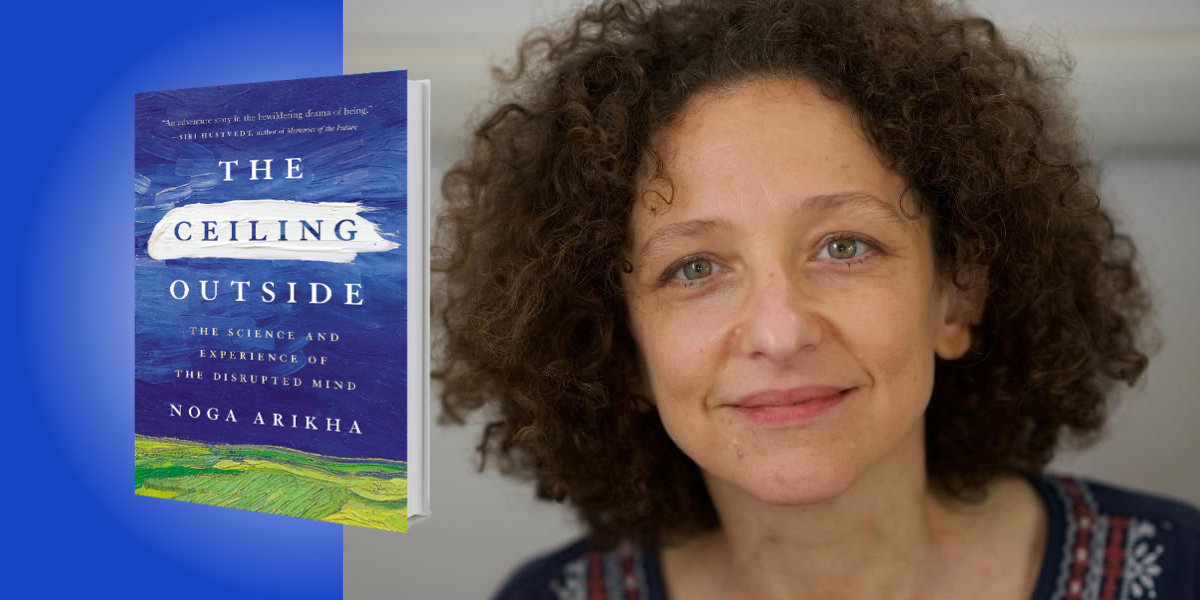

Noga Arikha is a philosopher and historian of ideas. The author of Passions and Tempers: A History of the Humours, she is associate fellow of the Warburg Institute and honorary fellow of the Center for the Politics of Feelings, London, and research associate at the Institut Jean Nicod, Paris.

Below, Noga shares 5 key insights from her new book, The Ceiling Outside: The Science and Experience of the Disrupted Mind. Listen to the audio version—read by Noga herself—in the Next Big Idea App.

1. What is the self?

Every day and everywhere, people suffer from neurological and psychiatric issues. But underlying them all is a basic question: what is the sense of self that is disrupted in these cases? When we contemplate ourselves, what do we see, feel, and experience? What is the self? When we relate to each other, who are we? Is there even such a thing as a self?

These are old philosophical questions. But nowadays the mind sciences, from neuroscience to psychology, are guiding us toward some answers. These answers cannot be final, and the questions remain open. But they are fascinating, and they may be helpful to those who sometimes wonder who they are, as well as to those who accompany patients with ailments so severe that they cannot make sense of what is happening in their lives—notably patients afflicted with dementia, as was my mother.

The Ceiling Outside looks at some of these old philosophical questions, and some of the scientifically informed answers, by telling the stories of patients who consulted a neuropsychiatry unit in a Parisian hospital. They or their families sought help because they suffered from strange ailments of unclear diagnosis that affected their sense of self, their sense of time, and their ability to find their way in the world—disrupting their family, social, and work lives. Vanessa, for example, awakes from a hypoglycemic coma, unable to recall the past ten years of her life. Is she the same Vanessa as she was before? Why and how did her amnesia happen? How does memory shape who we are?

“Why can’t she exit the tormented place she has been stuck in for years, even since she had surgery on that hand?”

2. Mental ailments can be psychiatric or neurological—but is there really a difference?

It is hard to identify the ailments such as those of Vanessa as either psychiatric or neurological. Neurologists focus on symptoms related to some sort of organic, cerebral change caused by accident or illness, while psychiatrists focus on behavioral disturbances of a so-called “functional” nature—that is, with no clear organic basis. The two realms diverged in the 19th century, and this book tells the story of how this split happened, and where this has left patients afflicted with mental illness.

Today, the improvement of imaging technologies and the multiplication of neurological data have changed what we can classify as organic and what as functional, so the division between the two realms is no longer so clear. In fact, it may not even be justified anymore. Vanessa’s brain scans, for instance, don’t reveal any clear lesion, but nor does she suffer from any identifiably psychiatric ailment. Patients such as she find themselves stuck in a no man’s land between medical specialties. Then there is Claire, who suffers from chronic pain, as do one in five people in the U.S. The pain is located in her hand, which she protects with a glove. Why does the pain seem to feed on itself, and why can’t she exit the tormented place she has been stuck in for years, even since she had surgery on that hand?

3. We must connect experimental science to the lives of individual patients.

I sat in on weekly clinical examinations anonymously, observing but never participating. Aside from Vanessa and Claire, there are six others, including Toussaint, who has acoustic hallucinations and thinks he is possessed, and Thomas, who has split himself into two personalities after losing his wife. These examinations left many questions open, and I tried to explore them with theories that are being developed not within the clinical setting, but within certain fields of experimental psychology and neuroscience. To understand the stories I heard, I turned to this fascinating, cutting-edge science, bringing it out of its academic fold and into the clinic, building a bridge between experimental science and the care of the individual patient.

“If the objective dysfunction is not found, then it belongs beyond the realm of medicine—it is ‘functional.’ The question then is: who can help?”

I think it is important to build these bridges also to help revise the disease model into which we are usually accultured, as potential or actual patients, and as carers. According to this model, there is a correspondence between a subjectively experienced symptom and an objective bodily dysfunction, and this dysfunction must be broken down into analyzable pieces in order to then be cured. But if the objective dysfunction is not found, then it belongs beyond the realm of medicine—it is “functional.” The question then is: who can help?

4. The mind-body connection runs deeper than you might think.

These theories take as a starting point that the brain cannot be studied without the body that it serves, and that the mind is the sum of brain, body, and environment all acting together dynamically. The person is never isolated, and how we understand disturbances in the sense of self cannot be divorced from the social and familial context. We can’t think of a brain in a vat any more than we can of a soul separate from the body, nor is there a clear cutting point that indicates when common ill-feelings become pathologies. The definitions of such pathologies, characteristic of what one calls “mental illness,” fluctuate, along with assumptions and knowledge about how the mind works.

Individual stories matter, and the book is structured around these stories. While no one trajectory is like another, whether in health or in sickness, in all of us there are mechanisms that underlie our sense of self, our emotional and cognitive states, and our capacity to interact and communicate. These mechanisms partake of the embodied sense of self, which the science I report on is helping us understand with increasing precision, and which shows how central interoception is to it.

“How we understand disturbances in the sense of self cannot be divorced from the social and familial context.”

To use a definition established by a group of scientists involved in this research, interoception is “the process by which the nervous system senses, interprets, and integrates signals originating from within the body, providing a moment-by-moment mapping of the body’s internal landscape across conscious and unconscious levels.” Studying interoception helps us understand our selves, our relationships, our emotional lives, and their disorders. When mental health becomes fragile, something has gone wrong with underlying interoceptive processing, and with the ability of the organism, of the embodied self, to thrive within the constantly changing environment—that is, to conduct homeostatic adjustments.

5. Dementia affects the self in myriad, surprising ways.

These theories are not yet known by the general public, and not yet established everywhere in mainstream psychology, many branches of which remain broadly cognitivist. Yet I realized, as I wrote the book, that they also help us understand dementia, and so I decided I had to report on my own journey of understanding, or bafflement, as I experienced my own mother losing large swathes of her memory. The CDC estimates that about 5.8 million people are afflicted with dementia in the U.S. alone, and the WHO estimates about 55 million cases worldwide. So it was important not just for me, I thought, to write about this experience.

There are various dementias, and it is not always easy to tease them apart. Sometimes, many pathologies together result in a range of symptoms. My mother’s dementia was of the Alzheimer’s type; we didn’t test her for its typical biomarkers, but the clinical presentation of her troubles pointed to it. At the beginning, her sense of time became confused, she forgot words, and mixed up faces, films, and stories. Gradually, she lost her long-term, so-called “episodic” memory. Memory, and the sense of time and continuity, are embedded within the body as much as within cerebral pathways. They, too, depend on interoceptive processes to some extent.

But my mother’s affect remained intact, and she was able to recognize and relate to us until she died. Her “self” as a mother remained. The sense of self is layered, and multiple—but emotional, embodied memory is its central core. She had been a poet, and was able to make wonderful statements during the course of her illness, one of which became the title of this book, which turned out to be a way of honoring her.

To listen to the audio version read by author Noga Arikha, download the Next Big Idea App today: