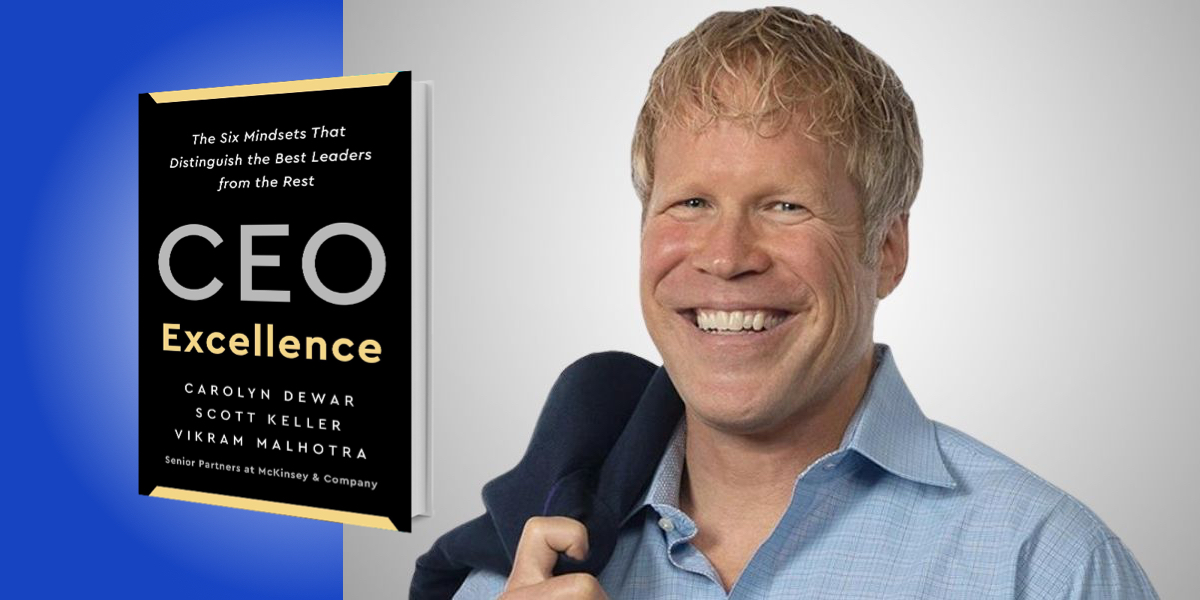

Scott Keller is a Senior Partner at McKinsey & Company. He is the author of six books, including Beyond Performance: How Great Organizations Create Ultimate Competitive Advantage. Carolyn Dewar is a Senior Partner at McKinsey & Company. She has published over thirty articles in the Harvard Business Review and the McKinsey Quarterly and is a frequent keynote speaker. Vikram (Vik) Malhotra is a Senior Partner at McKinsey & Company where he has worked since 1986. He has served on McKinsey’s Board of Directors and as McKinsey’s Managing Partner of the Americas.

Below, Scott shares 5 key insights from their new book, CEO Excellence: The Six Mindsets That Distinguish the Best Leaders from the Rest. Listen to the audio version—read by Scott himself—in the Next Big Idea App.

1. The CEO role is more important than ever.

According to the Edelman Trust Barometer, trust in CEOs to help us navigate pandemics, disrupted supply chains, labor shortages, geopolitical instability, and climate events has increased. But for government leaders, religious leaders, community leaders, and media leaders that trust has decreased. So there’s a strong mandate for CEOs to step up and make a difference on a broad societal stage.

And if you take a financial look at things, you see that high-performing CEOs, as you’d expect, definitionally, perform better—but to the tune of three times more total return to shareholders within an industry. If you look at the top quintile, the top 20 percent of value-creating companies across industries, they create over 30 times the economic value of the next three quintiles combined. That translates into jobs, GDP growth, and wealth creation for pension funds. So overall the CEO job is a really important role, probably more important than ever.

2. Very few people excel in the CEO role.

30 percent of Fortune 500 CEOs last less than three years in the role. Turnover rates are up 38 percent over the last 10 years. If you look at the chance that a CEO will take a company from average to top-quintile performance and value creation, they have a 1 in 24 chance of doing that, say the analytics.

So what help is out there for CEOs to achieve the excellence they aspire to? Well, there are many individual CEO biographies or autobiographies, but they’re usually interesting and profound because of the unique combination of the CEO’s personal profile, the company’s unique makeup, and the nuances of the external context in which they’re operating. They tend not to be highly generalizable across a lot of different situations. So there’s tips and hints that can be picked up, but it’s not really a field guide to how to excel in the CEO role.

“If you look at the top quintile, the top 20 percent of value-creating companies across industries, they create over 30 times the economic value of the next three quintiles combined.”

Then you look into academia, and you look at what the consultants have to offer. There’s a lot of generalizable information there, but it tends to be more of a descriptive nature: “Be a good relationship builder, show resilience, be a great strategic thinker, be decisive”—those types of things. And these studies rarely differentiate between great performers and average performers or even lower performers in the role. So our goal was to both define the role and decode how those who excel think and do things differently.

3. Being a CEO is more about spinning plates than finding silver bullets.

If you were to learn how to be a skipper on a sailboat, you would learn six things to manage all at once. You would learn “course made good,” which is adjusting for leeway and tide to get from A to B most directly. You would learn centerboard position, which is correcting for sideways drift. You would learn sail trim, which is getting the sail in the most efficient position. You’d learn boat balance, to ensure the boat doesn’t tip. You’d learn boat trim, which is keeping the boat level. And you would learn a lot about just being a skipper in terms of not dipping into the rum, motivating your crew, judging the weather, and more.

The point here is that you would learn six important things that you would need to do all at once. Similarly, there are six responsibilities that are core to the CEO role: direction-setting, aligning the organization, mobilizing through leaders, engaging the board, connecting with stakeholders, and managing your personal effectiveness. Those six responsibilities all need to be managed simultaneously all the time.

This is actually quite a liberating idea, because being great at being the CEO does not mean you have to be great at any one thing—you just need to be great at managing across them. It’s an integrative skill set. Johan Thijs, CEO of Belgian bank-insurer KBC told us, “I’m good at a lot of stuff. And perhaps I can do one or two things very well, but I’m not the best at it all. But that’s not important—what’s important is that I can balance everything together.” In short, it’s about spinning plates, not finding silver bullets.

“Being great at being the CEO does not mean you have to be great at any one thing—you just need to be great at managing across them. It’s an integrative skill set.”

4. There are six mindsets that make a difference.

From one mindset stems a thousand behaviors. For example, a Manchester shoe company sent two salespeople to Africa in the 1800s, and they got two telegrams back. One said, “Hopeless situation. No one wears shoes.” But the other said, “Glorious opportunity. No one has shoes yet.” And we found a core mindset on each of the dimensions of the role that really separated the best from the rest.

Let’s start with the direction-setting mindset. Imagine you’re handed the keys to a $30 billion ship full of 30,000 employees. It would be reasonable to have as your first principle, “Do no harm, and be super cautious about how we drive this thing forward.” But that’s not the type of mindset that our top-performing CEOs had. Of course they didn’t want to do any harm, but instead they thought, “How do we increase the speed? How do we go to a better destination? How do we find a better route with smoother water?” It’s a “fortune favors the bold” mindset. For Ajay Banga at MasterCard, it wasn’t about, “Let’s try and beat Visa”—it was, “Let’s actually kill cash, because that’s really the market we want to capture.” Or for Mary Barra at GM, it’s less about, “Let’s win in global automotive,” and more about, “Let’s transform transportation.”

When it comes to aligning the organization, it would be easy for CEOs to adhere to the aphorism that says, “Not everything that counts can be counted,” which essentially says, “The soft stuff matters, but it can only be done on a best-effort basis.” Our CEOs rejected that notion. Their mindset was, “Treat the soft stuff as the hard stuff.” They demanded the same level of rigor and discipline on the people side of things as they did on the operational side of things.

In terms of mobilizing through leaders, a lot of CEOs might gravitate toward, “Look, we have to get the right mechanics in place—the right meetings at the right time with the right people on the right topics.” Our top CEOs said, “No, no, no—the first thing to think about is the psychology of the team.” Feike Sijbesma, the CEO of DSM, talks about how the bricks are useless without the cement.

“Our top-performing CEOs had the mindset of, ‘I’m going to do what only I can do. All else gets delegated to others and handled in different ways.’”

Let’s move on to the board engagement responsibility, and the mindset there is not one that says, “My role is to manage the board.” It’s one that looks at the board and sees this valuable asset to be tapped into and thinks, “How do I help my board help my business?” That translates to very different behaviors in relation to the amount of transparency they have, the amount of forward-looking items they put on the agenda, how they influence the board’s composition, and how they think about educating the board.

Next we have the responsibility of connecting with stakeholders. A lot of CEOs would gravitate to, “Okay, who do I meet, and when? What do I need to say?” Whereas for our top CEOs, the focus was on the motivations. The mindset was, “Let’s start with why.” A simple example would be Reed Hastings from Netflix—when he meets with reporters, he understands that they want to be truth-tellers, but that they’re forced to be entertainers as well. So if he wants to get his message across in the best way, he’ll give them both.

That takes us to the final mindset, which is around personal effectiveness. The mindset that many people default to is to do whatever needs to be done. That’s perfectly rational and quite laudable, but it’s not the mindset our CEOs had. Our top-performing CEOs had the mindset of, “I’m going to do what only I can do. All else gets delegated to others and handled in different ways. So everything still gets done, but I’m going to add the value that I uniquely can add.” And part of that is having that balcony view across all the different dimensions of the role.

5. These lessons matter everywhere.

The learnings we picked up from these CEOs, which are forged in the crucible of some of the most complex leadership environments, are actually quite applicable to less complex leadership environments. And given that, we are hopeful that this work will help leaders everywhere—not just CEOs—be more effective.

To listen to the audio version read by co-author Scott Keller, download the Next Big Idea App today: