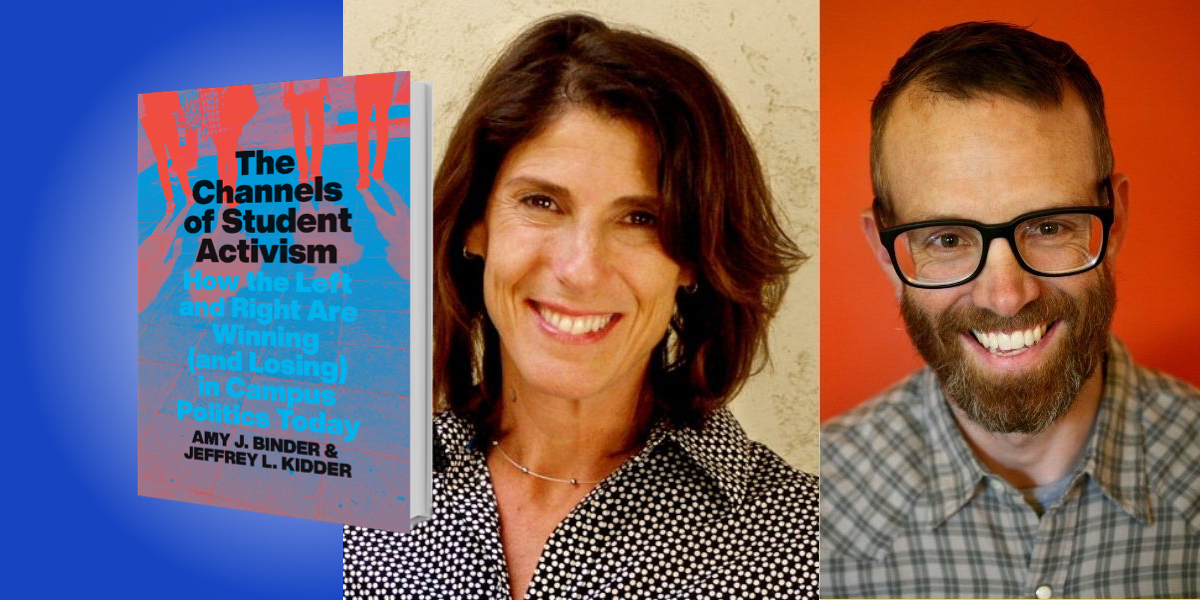

Jeff Kidder and Amy Binder are both sociology professors who have spent many years studying politically engaged college students. Binder teaches at University of California, San Diego. Kidder teaches at Northern Illinois University.

Below, Jeff and Amy share 5 key insights from their new book, The Channels of Student Activism: How the Left and Right Are Winning (and Losing) in Campus Politics Today. Listen to the audio version—read by Jeff and Amy themselves—in the Next Big Idea App.

1. We need to think about the ways institutions and organizations channel student activism.

In recent years, there has been frequent news coverage of protests at colleges and universities. However, there has been very little attention paid to the forces within schools and outside organizations that can substantially encourage or discourage the types of activism taking place. So, instead of just examining the choices individual students are making, we turned our sights to the social structures that make certain thoughts and actions more or less likely. The implications of campus politics have far-reaching consequences. Many of tomorrow’s political leaders are college students now. The debates and fights taking place often spill into American popular culture, so it is critically important to understand the structural forces shaping the content and tenor of campus politics.

As we talked with college students, professors, and leaders of organizations about their political activities and motivations, we realized that there are profound differences in how conservative and progressive activists are trying to achieve their goals—the tactics and strategies behind these different political mobilizations. In essence, there are two main channels that guide students toward some outcomes and away from others.

What we call “the progressive channel” draws students inside their colleges and universities. Students who are leftist or liberal receive significant organizational support on campus, and generally feel that their politics resonate with their schools’ cultural ethos. In addition, progressive students receive financial backing and hands-on training for their activism through multiple campus units, such as multicultural centers, diversity offices, and student affairs programming.

The “conservative channel” functions a bit like an outside insurgency. Right-leaning students are a political minority, and many feel isolated and unsupported by peers and faculty. However, conservative students are able to tap into a powerful external ecosystem of think tanks and non-profits designed to serve as an alternative to higher education’s liberalism. These outside organizations offer a great deal of money, training, and support to activists willing to stage bold events in the name of right-leaning causes on their campuses.

“There are profound differences in how conservative and progressive activists are trying to achieve their goals.”

2. Conservative activists rely on organizational support from outside of academia.

The conservative channel is nicely illustrated in the examples of Amanda and Ariel, two right-leaning students. There are a lot of things that distinguish Amanda and Ariel. Amanda revered bipartisanship and political moderation. Ariel was an enthusiastic booster of President Trump. These two women became representatives for very different segments of the conservative channel. Amanda was a leader of her school’s outreach program for the American Enterprise Institute, a well-known conservative think tank in Washington, while Ariel was the president of her school’s Turning Point USA chapter, a firebrand organization that encourages students to take part in America’s culture wars with provocative sloganeering and raucous protests.

Differences in political stylings aside, both of these groups are heavily financed—giving them resources to excel in their areas of focus. The American Enterprise Institute supports right-leaning scholars and nurtures future policymakers through a well-funded annual internship program and a recruitment funnel for full-time jobs. Turning Point hosts all-expenses paid conferences for its members and provides regional field representatives who offer feedback and money to support students’ confrontational actions on campus. Further, both groups are unified in creating skepticism about higher education. Conservative students’ skepticism towards higher education was palpable among the activists we interviewed.

Colleges and universities—while far from perfect—are part of our nation’s democratic bedrock. But the conservative channel is helping to undermine what was once considered a basic civic value: public support for educating our citizenry.

3. Progressive activists turn to resources available from within academia.

The progressive channel is primarily funded by school institutions alone. This might seem surprising because liberal organizations and donors give hundreds of millions of dollars to colleges and universities each year. However, these outside deep pockets don’t extend to progressive activism the same way they do in the conservative channel, presumably because left-leaning philanthropists assume academia is already serving progressive interests. But this difference between the channels has at least two major consequences.

“It was hard for us to find a progressive activist confident in their job prospects.”

The first consequence is insularity. The lower the material and ideological support for students from the outside, the more activists must depend on their campuses. The more they rely on institutional supports, the fewer ties students forge with outside organizations and the influential figures running them. This is especially problematic when seniors start looking for politically-oriented careers after graduation. In fact, it was hard for us to find a progressive activist confident in their job prospects. Dexter, for example, spent years as a leader of his school’s College Democrats chapter, but he was at a loss for how his experiences would translate into a paid position. All of this is to say that progressive activists do not have the recruitment funnels found in the conservative channel.

The second consequence is burnout and cynicism when progressive activists feel their schools are failing to achieve diverse and inclusive environments. This is especially true for students of color, who often feel administrators are merely paying lip-service to social change while maintaining policies that marginalize underrepresented student groups.

The progressive channel—both because students lack support from the outside and they become cynical about promises made from the inside—leads to skepticism about higher education among leftist and liberal students, too.

4. Speech is a wedge issue, uniting conservatives and dividing progressives.

The supposed curtailing of speech rights on college campuses continues to make headlines. Much of the problem is articulated in the generations-old question, “What’s the matter with kids these days?” But perhaps we’ve been asking the wrong question. If we think about campus politics through the structural lenses of organizations, we see that debates about free expression in higher education involve more than the innate sensibilities of students. They’re increasingly about how on- and off-campus political groups mobilize activists in very different ways.

A key tactic within the conservative channel is funding provocative events and inviting inflammatory speakers to campuses. When successful, these episodes produce outrage from the left, allowing the right to counterattack with charges of cancel culture. Conversely, school leaders and outside progressive organizations have been slow to generate resources for students on the left. As a consequence, progressive students lack a clear set of guiding principles for balancing the virtues of free expression with their goals of increasing diversity and inclusion. This often leaves liberals and politically moderate students uncomfortably wrestling with extremes. They want to reject hateful forms of speech popular in much of conservative discourse, but they also are wary of the far left’s censorious impulses.

“Progressive students lack a clear set of guiding principles for balancing the virtues of free expression with their goals of increasing diversity and inclusion.”

Students need help understanding the tensions between these competing stances, but outside organizations have hardly come to their aid. Without clearer institutional guide posts, progressive students—and students of all political persuasions—lack the necessary tools to make practical sense of free expression. While conservative activists have alternative organizations to lean on, everyone else has been muddling through on their own. A progressive version for free expression requires a nuanced appreciation for communal as well as individual rights.

5. We need renewed dedication to productive civic engagement within the academy.

Our research produced worrisome findings: students on the left and right are mobilized so differently as to be tribal, and both channels produce cynicism toward higher education. Thankfully, there are efforts to abandon divisive politics in favor of dialogue that builds empathy.

BridgeUSA and Sustained Dialogue are two good examples of outside organizations committed to confronting political polarization. There are clear differences between these groups, but they share important similarities. They encourage appreciation of differences in perspective, truly listening to those perspectives, and questioning our assumptions. The groups are not meant to be forums for debate, or what one student called “dominance disputes,” but rather as places where participants can put themselves “in the skin of other people. . .It’s about building character,” according to another of our student interviewees.

Members of both organizations say that students should not have to compromise their political convictions to participate in constructive dialogue. These groups are not trying to make people politically moderate, nor bipartisan. They want to transcend partisanship to improve communication across the ideological spectrum.

Such groups are not the antidote to polarization, but they present an important alternative to the contentious student activism that has defined both conservative and progressive channels.

To listen to the audio version read by co-authors Jeff Kidder and Amy Binder, download the Next Big Idea App today: