Rachel Rabkin Peachman is a journalist who covers health, science, and family. She has written for The New York Times and Consumer Reports, among other publications. Anna C. Wilson is a pediatric pain psychologist and associate professor at Oregon Health & Science University.

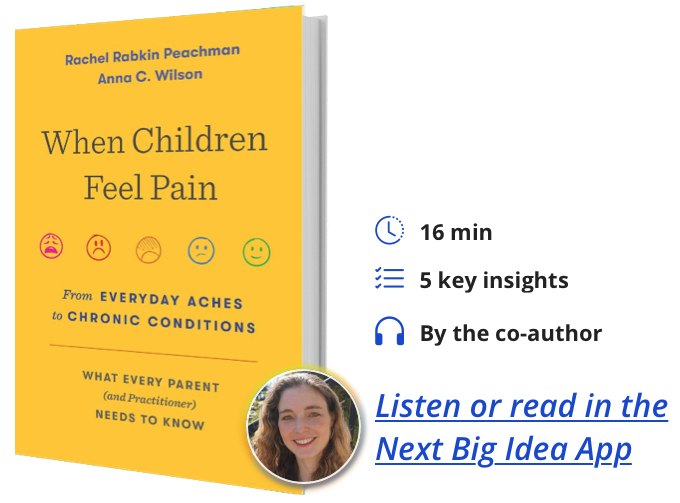

Below, Rachel shares 5 key insights from their new book, When Children Feel Pain: From Everyday Aches to Chronic Conditions. Listen to the audio version—read by Rachel herself—in the Next Big Idea App.

1. Children’s pain management has been sidelined for too long.

Kids are hurting. An estimated 20 percent of children in the U.S. have pain that occurs every week or more. About five percent of children in the U.S. deal with moderate to severe chronic pain that impacts day-to-day functioning. Despite these alarming numbers, about half of children with chronic pain have not been believed by adults, most often by their medical providers and their own parents.

In fact, throughout most of modern medical history, pain in children has been dismissed, undertreated, or ignored. But it’s not because there is a lack of love for children or even a lack of treatments. It’s essentially because pain—especially pain in children—is poorly understood. It’s subjective, hard to measure, and often invisible. When pain is misunderstood, it gets sidelined.

It has taken decades for medical professionals to acknowledge that children feel pain as intensely as adults. As recently as the 1980s, babies were undergoing invasive medical procedures (like open-heart surgery) without anesthesia or pain-relieving medications because physicians believed that infants’ nervous systems were not mature enough to feel pain. There wasn’t even a textbook devoted to pediatric pain until 1987—just 35 years ago.

To this day, many people don’t realize that children can have chronic pain, which is pain lasting longer than three to six months, and tends to happen when neural pathways become hypersensitive, causing even small sensations to trigger intense pain signals.

While there’s now a large body of research proving that children do feel pain as intensely as adults do, managing that pain is too often an afterthought, and this can have devastating consequences.

2. Short-term pain can have long-term consequences.

We’ve all heard platitudes about pain: No pain, no gain! or You just need a Band-Aid or It’s not that bad; it will be over soon. But what these phrases miss is that each episode of pain impacts the way we respond to future pain in the long term. Our early exposures to pain can be some of the most critical because they can shape developing neural pathways. So even though babies and children may not consciously remember painful experiences, their nervous systems will.

“Every painful experience builds on the last.”

One of the most compelling studies about this was published in The Lancet in 1997. The researchers looked at infants in three categories: baby boys who had undergone circumcision without receiving pain management; baby boys who had been circumcised and had been given a topical pain treatment; and baby boys who had not been circumcised. The researchers then evaluated these babies when they received vaccinations at 4 months and 6 months.

They found that the infants who had not been circumcised cried the least after getting their shots. The infants who cried the most were those who had been circumcised without pain management. This tells us that past experiences with pain can affect future responses to pain, and that when painful procedures are not well-managed, an infant’s nervous system can become more sensitized. In other words, every painful experience builds on the last.

Many other studies have found that poorly managed pain early in life can also increase children’s risk of developing chronic pain. Once a child develops chronic pain, it can be difficult to rein it in. Up to two-thirds of children who experience chronic pain go on to have chronic pain as adults. So how we treat pain in children is not just about the discomfort they feel at that moment. Treating children’s pain effectively now—whether it’s a vaccination, a broken bone, or chronic headaches—may be critical to reducing the incidence of chronic pain in adults.

3. Parents can have a big influence on alleviating their children’s pain.

If you’re a parent, ask yourself: Do I know how to help my kids when they’re in pain? There are mounds of parenting books devoted to advice on feeding children, encouraging their language development, and helping them sleep. But how many parents think about how to respond to their children when they’re in pain—which is one of our most primal human experiences?

Think about acute pain, which is the type of pain you feel when you break a bone or touch a hot stove. It doesn’t feel good, but its purpose is to protect you from further harm—your body’s alarm system that something is wrong. We can influence our perception of this pain by changing the environment around it and our associations with it.

For instance, we can lessen the pain children feel when getting a vaccination or a blood draw by holding them, helping them take deep breaths, distracting them with videos, letting them suck on something sweet, and even talking with them about the experience afterward in positive terms so that their memories don’t negatively influence future experiences with pain. It’s also key for parents to stay calm, because a stressed parent indicates to our kids that there is something to fear, which will heighten their anxiety and pain.

“Chronic pain is best treated with a multi-disciplinary approach that may or may not include medication.”

Treating chronic pain is different. Unlike acute pain, chronic pain does not serve as an alarm system for protecting us. Chronic pain is best treated with a multi-disciplinary approach that may or may not include medication. It can include cognitive behavioral therapy, physical therapy, breathing exercises, and guided meditation. It can also include behavioral modifications.

To understand how treatments work, it’s helpful to know that stress and lack of sleep can make pain worse. Also, dwelling on pain and avoiding activities can cause kids to focus on the pain, and feel isolated and depressed, which then feeds into the pain. Parents can help by working with their kids to find ways to alleviate their stress, maintain a consistent sleep schedule, and keep up with normal activities. This can feel difficult, but the payoff is worth it. One teenager I spoke to found that the fewer activities she did because of her chronic migraine pain, the more her mood deteriorated. But when she participated in things, even if that was just going to school for half the morning or meeting a friend for an hour, her mood improved and she was able to cope much better when she had intense migraines.

4. Medication can be used safely—even opioids.

Many people worry that giving strong pain medications to children and babies could damage their developing brains or lead to opioid addiction. But research shows that those fears are largely unwarranted when clinicians appropriately prescribe pain relievers and supervise their patients.

When trying to alleviate acute pain, the medications typically used include over-the-counter analgesics (like acetaminophen), non-steroidal anti-inflammatory medications (like ibuprofen), and prescription opioids, which essentially block pain signals in the central nervous system.

Yes, I said opioids. While we are in the middle of a deadly opioid epidemic in the U.S., these medications do have an important place in managing children’s acute pain in certain situations. For example, opioids can be effective and necessary when treating a child’s pain after surgery. Opioids may also be critical for children with painful diseases, like cancer. Still, opioids can have serious side effects—including nausea, constipation, cognitive impairment, and the risk of misuse and overdose if they’re not taken under the supervision of a knowledgeable physician.

Keep in mind that no medication is a magic pill, and that medications work best as part of a multifaceted plan. Regardless of what condition a child is facing, the medications they take should be used along with psychological and behavioral approaches.

If your child is prescribed opioids, ask the clinician if you should consider nonopioid pain-relievers first. If opioids are necessary, talk to the prescribing doctor about the safest ways to use them, and when and how to wean off the medication.

5. Pain is personal and should be taken seriously.

What we feel, and how much we hurt, is dependent on the brain’s interpretation of a physical sensation and on the brain’s assessment of many psychological and contextual factors, including the circumstances of the pain, previous experiences, and emotions like stress.

“How we perceive pain is extremely individual and situational.”

That’s why when you stub your toe, you might perceive a drastically different pain level than someone next to you who experiences the exact same injury. Your brain bases its response on the information it has learned in your life, in your body, and no one else’s. How we perceive pain is extremely individual and situational.

It’s important to remember this when children come to you for help with their pain. What may not seem like a big deal to you may feel like a very big deal to a child. Believe your children. Far too often, kids with pain are stigmatized, devalued, and even ostracized. This is not just awful on its own, but can also lead to delayed diagnosis, treatment bias, and poor health outcomes. Notably, pain-related stigma is more likely to happen to girls, women, racial minorities, and gender-fluid individuals than to white boys and men.

For so many of the children I spoke to and many of my co-author’s patients, one of the hardest things about chronic pain is that people don’t understand it, or simply don’t believe it’s real. One mother talked about how it took months for doctors to take her teenage daughter seriously, despite her extreme pain. “We couldn’t understand why no one would help her,” she said. “She was screaming in agony, thrashing, fevered, and sweaty, and they wound up admitting her for about a week but there was still a lot of skepticism about her pain.” This child was eventually diagnosed with Ehlers-Danlos Syndrome, which is a genetic disorder that causes excruciating pain. Regardless of what was causing this child to feel pain, her pain was always real. The sooner parents and medical providers acknowledge it, the sooner it can be tackled.

Imagine if we all began to take a more thoughtful approach to pain, starting with when children have their earliest experiences with it. Maybe that’s the day they’re born, and a nurse draws blood from their heel to test for congenital conditions. Or maybe it’s when a toddler falls and needs stitches. Or when a teenager develops a backache after a sports injury. What if we could learn to spot that pain better, acknowledge it, and treat it before those developing neurons get out of control? Well, we can. The more we help children deal with pain now, the more we can stop the development of chronic pain in the next generation of adults.

To listen to the audio version read by co-author Rachel Rabkin Peachman, download the Next Big Idea App today: