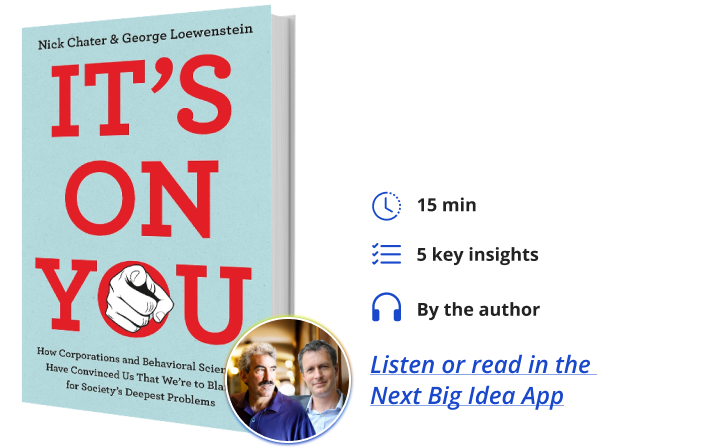

Below, co-authors Nick Chater and George Loewenstein share five key insights from their new book, It’s on You: How Corporations and Behavioral Scientists Have Convinced Us That We’re to Blame for Society’s Deepest Problems.

Nick is a professor of behavioral science at the Warwick Business School. His friend and longtime collaborator George is the Herbert A. Simon University Professor of Economics and Psychology at Carnegie Mellon University.

What’s the big idea?

Focusing on individual behavior is an appealing but largely ineffective way to solve major social problems. Lasting change comes from redesigning the systems, rules, and incentives that shape those behaviors in the first place.

Listen to the audio version of this Book Bite—read by Nick—below, or in the Next Big Idea App.

1. The I-Frame and the S-Frame—the story of nudge.

Big social problems—whether the climate crisis, obesity epidemic, failure to save adequately for the long term, or many others—can easily appear (if one doesn’t think too deeply) to arise from individual failings. People seem careless about their carbon footprint; they’re imprudent about saving; they’re thoughtless about their diet. It seems natural to conclude that simple human psychological frailty is the root of these problems. And if people are the problem, then people need fixing.

This perspective takes what we call the I-frame, or individual frame. It sees social problems as emerging from individual shortcomings. If you take this view, then the way to solve these problems is to help people live better lives—to change individual behavior so that carbon footprints are reduced, diets improve, saving increases, and so on. Part of the solution will be education; part will be better information; and part will be the idea of nudging: redesigning choices and information in subtle ways that make a meaningful difference.

These nudges might involve smaller plate sizes, feedback about your neighbors’ energy consumption, or default enrolment in pension schemes. Such changes don’t restrict freedom or alter economic incentives in any heavy-handed way, but they gently steer behavior in the “right” direction.

When Richard Thaler and Cass Sunstein’s book Nudge appeared in 2008, it felt like our moment—a chance for behavioral scientists and psychologists to help reshape society without relying on the traditional policy levers of taxes, subsidies, and regulations. However, things didn’t quite work out that way.

2. The seductive naturalness of the I-Frame perspective.

The I-frame perspective on social problems, embodied in Nudge, was incredibly attractive to us as people who study individual behavior. But it was also extremely attractive to politicians on both sides of the Atlantic, to large parts of the behavioral economics field, and—perhaps most importantly—it simply feels psychologically natural to all of us.

“We don’t think about the rules of the social, economic, and political games we are playing.”

Humans have evolved to navigate small-scale social interactions with individual people. We are accustomed to understanding the social world in terms of individual characteristics—how thoughtful, prudent, smart, selfish, or generous someone is. When explaining everyday behavior, we naturally focus on individuals, not on the complex systems of rules, regulations, and norms in which we are embedded. We don’t think about the rules of the social, economic, and political games we are playing.

This focus on the individual is sometimes known by psychologists as the fundamental attribution error: the tendency to explain behavior in terms of personal traits rather than in terms of the social, political, and economic environment that shapes that behavior. That individual focus makes us see social problems in individualistic terms.

For example, consider a recent nudge trialed in Switzerland. Energy consumers were defaulted from their standard tariff to a slightly more expensive sustainable tariff, and many people did switch—whether consciously or not—to that greener option. On the face of it, this looks like great news: more people on green energy, the climate saved one default at a time. And more broadly, it reinforces our natural inclination to think that the key to solving social problems is by helping individuals make better choices.

3. The I-Frame Doesn’t Work.

The difficulty is that, to create powerful social change, we need to change the system. We need to act at the S-frame level.

We have spent almost two decades trying to get individual-level behavioral change—the I-frame—to deliver meaningful results. But it turns out that most nudges don’t work, or at least only work to a small degree. Meta-analyses consistently reveal small or even null effects, and sometimes effects that backfire.

“We need to act at the S-frame level.”

Sometimes the failure is baked in from the start. Consider the Swiss green-energy example. Suppose many consumers are switched onto green energy, as they were. This doesn’t increase the amount of green energy available. No new hydro, solar, or wind power is built as a result. The nudge simply reallocates the existing green energy among customers. As some become “greener,” others inevitably become “less green.”

4. The corporate sleight of hand.

To create real change, we need to alter the rules of the social, political, and economic games we’re playing. That means good old-fashioned taxes, subsidies, and regulation. Directly targeting individual behavior is, in practice, a distracting sideshow.

But large corporations seem strangely drawn to these ineffective I-frame solutions:

- Who invented the carbon footprint? British Petroleum.

- Who sponsored the “Crying Indian” anti-litter campaign? The packaging and drinks industry.

- Who popularized the concept of jaywalking, supposedly to reduce accidents? The automotive industry.

And so on. Is this because corporations naïvely believe that nudges are a genuine substitute for radical systemic action on climate change, or for major reforms in packaging, recycling, or road design? Not at all.

There is a recurring pattern: corporate interests consistently promote an individualistic, I-frame perspective on social problems (even though they know it will be ineffective) while simultaneously lobbying behind the scenes to ensure the rules of the game remain in their favor.

While publicly urging individuals to “go on a low-carbon diet,” the fossil fuel industry is at the same time pushing hard against regulations that would actually threaten their bottom line.

5. Green Eggs and Ham.

For most deep and persistent social problems, individual behavior change is largely irrelevant. What we really need is major systemic reorganization. Consider climate change: we need carbon pricing, large-scale support for R&D, and policies that accelerate the adoption of green technologies. The same is broadly true for the obesity crisis, pension reform, and the challenges posed by inequality.

We may disagree on the fine-grained details, but the general direction of travel is not in doubt. Persistent social problems persist not because the necessary systemic changes are mysterious, but because powerful interests work actively to prevent them. And they have an additional advantage: they can exploit a deep psychological lever within all of us—our bias toward the status quo.

“Persistent social problems persist not because the necessary systemic changes are mysterious.”

If humans evolved in small, precarious environments, an aversion to change is understandable. But when we face complex institutional systems that are, in many ways, rigged against the public interest, this intuitive suspicion of change becomes a vulnerability—one that those who benefit from the status quo are only too willing to exploit.

Yet, human history is full of examples of dramatic systemic shifts that greatly improved people’s lives, often against the determined resistance of elites. Our bias toward the status quo is not only a curse; it is also a blessing. Once we transition to a new way of living, we often find that we rather like it.

Dr. Seuss captured this perfectly in Green Eggs and Ham: the protagonist fiercely resists trying something new under any circumstances—“I do not like them in a house… here or there… anywhere”—only to discover that the dreaded dish is delightful after all. So it has been with seatbelt laws, smoking bans, and, to some extent, congestion charging. And on a larger scale, with the creation of the welfare state, the abolition of slavery, the emancipation of women, and many more transformations.

The very psychology that inclines us to cling to familiar systems can also help us rapidly adapt to—and even embrace—systems that work better and serve the many.

Enjoy our full library of Book Bites—read by the authors!—in the Next Big Idea App: