Michael Doyle is a University Professor at Columbia University appointed in the School of International and Public Affairs, the Law School, and the Political Science Department. He served as UN Secretary General Kofi Annan’s assistant secretary general for policy planning. He also later chaired the UN Democracy Fund, set up by the U.S., India, and a number of other democracies in the UN to promote nonpartisan, grassroots democracy.

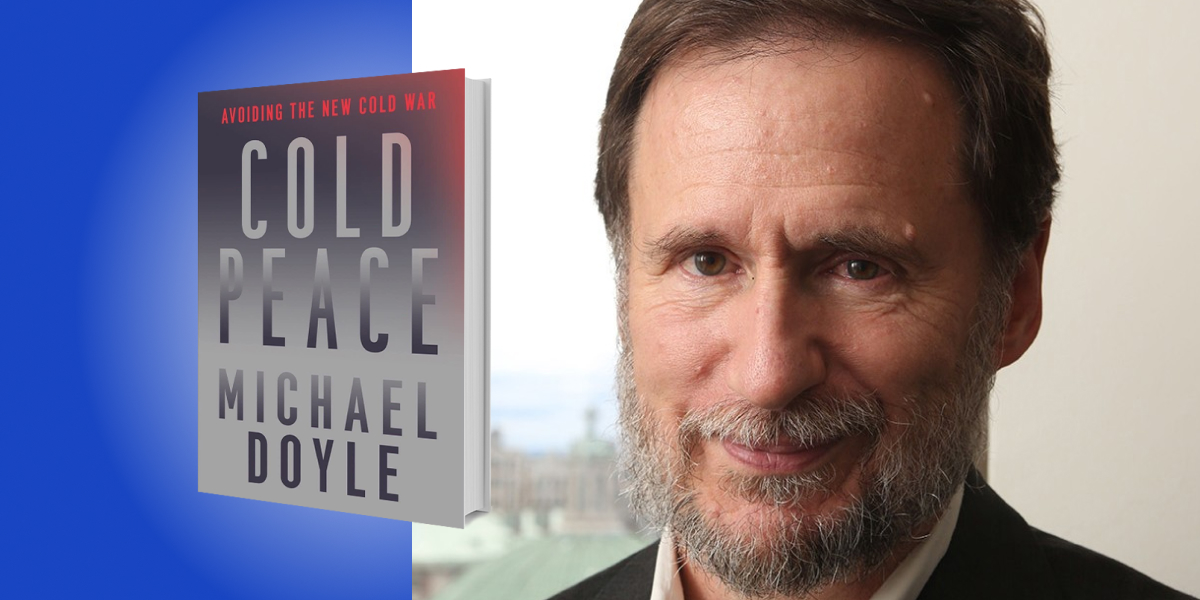

Below, Michael shares five key insights from his new book, Cold Peace: Avoiding the New Cold War. Listen to the audio version—read by Michael himself—in the Next Big Idea App.

1. The New Cold War is new but also resembles the first Cold War between the US and the Soviet Union.

The invasion of Ukraine is the first proxy war of the New Cold War. When Putin invaded in February, 2022, Ukraine valiantly defended itself. We do not know what the outcome will be, but what we can see is how the invasion divided the world. Russia had the diplomatic support of China and other autocracies; Ukraine has the support of NATO and its wide coalition, mostly consisting of democracies.

On the other side of the world, we see something similar. President Xi Jinping threatens to reunite Taiwan with China by force and wants to be able to do so by 2027. President Biden has said the US will defend the island, a self-ruling democracy.

Thus, many are rightly absorbed in the survival of Ukraine and the future of Taiwan. But an equally pressing question is whether the looming New Cold War that fuels the Ukraine War and Taiwan tensions can be contained. Can global strife be managed in order to rescue the vital international cooperation needed to address existential global challenges like climate change?

The Cold War (1948 -1990) was a revolutionary conflict over interests and legitimacy. Soviet leader Khrushchev at the UN General Assembly once threatened the West with “We will bury you” (he meant not nuclear war, but outcompete industrially). It was a binary bipolar conflict between blocs, ideologies, and systems of government: US vs USSR; Capitalism vs Communism: Democracy vs Dictatorship. There was trust and cooperation within the blocs, exemplified in the NATO and Warsaw Pact. In each of those agreements were similar values and hegemony. But Cold War distrust and rivalry loomed between them.

“Can global strife be managed in order to rescue the vital international cooperation needed to address existential global challenges like climate change?”

Post Cold War (1990-2012) was a period of pacification. Shared values were embodied in the statement of the Vienna Conference of 1993 that human rights were universal, not just Western, as they had been seen in the Cold War. Geopolitics and geoeconomics were unipolar, with the US providing order, and globalization seemingly spread the benefits of prosperity. The UN was active and great powers—the US the EU, Russia, and China—were closer to trust and cooperation than they had been in more than a century.

Today’s “New Cold War” or “Cold War II” escalated with Putin’s first invasion of Ukraine and conquest of Crimea in 2014. UN Secretary-General António Guterres described the New Cold War as follows: “The Cold War is back with a vengeance, but with a difference” he stated but then warned, “The mechanisms and the safeguards to manage the risks of escalation that existed in the past no longer seem to be present.”

This New Cold War is thus divided like the first Cold War into two great power blocs. The US, NATO, and allies once again pushing against Russia and China, in a “no limits partnership”. The New Cold War also turned into an ideological contest between democracy and autocracy, according to President Biden.

2. The instruments of the New Cold War, including cyberwar and industrial espionage, make for strife, but not direct military clashes.

The instruments of the New Cold War are proxy wars, like Ukraine, but even more so, cyberattacks. Examples include the criminal ransomware used on the Colonial Pipeline by the Russian cyberunit called DarkSide, or a similar software used on the JBS food chain. This ransomware has also been used on hospitals, utilities, and transport networks. There is also cyber sabotage, as with the US/Israel hack on the Iranian uranium refinement process that destroyed its machinery.

The New Cold War has also seen industrial espionage. China is engaging in extensive spying on US aerospace and pharmaceutical industries, in order to steal technology. In 2021, Microsoft Exchange experienced a hack by Hafnium, which may have been backed by China.

The most destabilizing instrument of this cyber warfare, however, is political subversion. The more prominent of these is Russia hacking into the 2016 US and EU elections. China also alleges that the US encouraged or organized the 2014 “Umbrella and Extradition” demonstrations in Hong Kong.

3. The New Cold War has deep sources in changing global power dynamics between the US and China and in domestic drivers of suspicion.

The New Cold War has deep sources that cause two-fold strife. The first is the so-called “Thucydides Trap” after the rivalry between ancient Athens and Sparta. It is also referred to as hegemonic competition. This occurs when a challenger launches a war to win control of the global political order. This can also happen when the holder of that order attacks to preserve control. In a widely cited political study by Graham Allison, it was found that only four of the historic hegemonic competitions had a peaceful outcome. All the rest were resolved by war.

These competitions also produce deep incentives for strategic confusion in messaging. The existing holder of hegemony seeks to sound the alarm to mobilize allies against a challenger. The challenger consistently claims it has no revolutionary ambitions. This means that the messaging coming from the holder and the challenger is simply designed to confuse or disavow the other side’s narrative.

“Democracies typically have short-term thinking, but they are accountable to their public.”

The second New Cold War strife is over domestic systems. We see a contest between democracy and autocracy. Democracies typically have short-term thinking, but they are accountable to their public. Autocracies often take the long view, but they are unaccountable to a wide public.

There are also many contentious economic incompatibilities in this conflict. Russia and China are corporatists, which means the state owns, directs, or manipulates media through an oligopoly; and the economy is controlled through an oligarchy. This is in rivalry with market capitalism, which is found in the United States and European Union. In this system, the state and private enterprises are separate. This produces deep competition. Western firms think they are competing against states, like Russia, rather than other private firms.

Ideologies also clash. In the situation with Russia and China, we see claims of sovereign nationalism that clash with the liberal internationalism of the West. This pits the liberal human rights of the West as a contest to the legitimacy of Russian and Chinese autocracy. Undemocratic governments are viewed generally as illegitimate. On the other side, Russia and China decry the cultural freedoms of liberal and social tolerance in the West as deeply subversive of a stable cultural order.

4. Despite the tension, cooperation is possible.

A Cold Peace détente, in which mutual subversion is taken off the table and cooperation is tried, is both desperately needed and possible—especially in order to solve global challenges like climate change and future pandemics.

The New Cold War is not likely to be as extreme a confrontation as the first Cold War. It’s not a simple contest, in the way that the USSR and US were in the past. Now, the EU equals US economically and the rivalry between the US and China is mostly linked to security and the economy. The rivalry between the US and Russia is dominated by concerns over security and the military. It’s also not a simple economic confrontation of opposites, like Capitalism vs Communism. For example, in 2021, China had more billionaires than the US.

.

Another difference in the two conflicts is that now, many of the respective allies are reluctant. Germany, France, Japan, and India doubt US consistency and have profitable ties to Russia and China. There is also a “New Nonaligned Third World” emerging from the developing and developed world. India, many African states, and Brazil see Ukraine as remote. Issues of poverty and food are far more proximate for them.

“The New Cold War is not likely to be as extreme a confrontation as the first Cold War.”

Moreover, there are now deep common interests among China, Russia, and the US, as well as the rest of the world, that counter confrontation. China and the US, and China and the EU are each other’s best customers. Even in the first Cold War, we saw realms that were open for cooperation. The Strategic Arms Limitation Treaty is an example of this, which managed a nuclear standoff. The case for arms control with China and Russia today is even stronger. The US spent $11 trillion on defense in the first Cold War against a much less dynamic USSR. China today has nearly triple the US population and is growing economically about twice as fast. An arms race with China would, these days, preclude all other global public investments in things like preventing future pandemics or dealing with global warming.

5. The moral case for compromises and reforms that launch a Cold Peace is overwhelming.

The five following compromises can lead us to imagine a Cold Peace going forward. The first would be to support Ukraine’s self-defense, without an armed attack on Russia proper (not including its annexation of Crimea). This compromise would also need to include the fate of Crimea, including possibly a referendum to decide Crimea’s fate as either Russian or Ukrainian.

The second involves Taiwan. The US should formally acknowledge “One China.” There are historic grounds to see Taiwan and the Taiwanese people as part of the greater Chinese community. This should only happen if Beijing is willing to promise to not forcefully seize the island. Rather, it would use peaceful persuasion to achieve a legitimate resolution between the two countries. In the meantime, the US could assist Taiwanese self-defense not of “independence,” but of Taiwanese security and autonomy.

The third compromise involves cyber warfare. An agreement needs to happen regarding The Three No’s: no cyber sabotage, no industrial tech theft, and no political subversion.

Another compromise would include tri-lateralization of nuclear arms control. We need to bring China into the mix. This would require a new “SALT” treaty that includes the US, China, and Russia.

The final compromise involves domestic US reforms. These reforms would rebuild the vibrancy of our welfare state and restore the promise of the American middle class. This would enhance our democratic stability and resilience which is needed in light of the inevitable competition with China and Russia.

Each of these compromises is complicated and none will be easy. But we owe the next generation a try at Cold Peace cooperation in order to avoid the confrontation of a New Cold War.

To listen to the audio version read by author Michael Doyle, download the Next Big Idea App today: