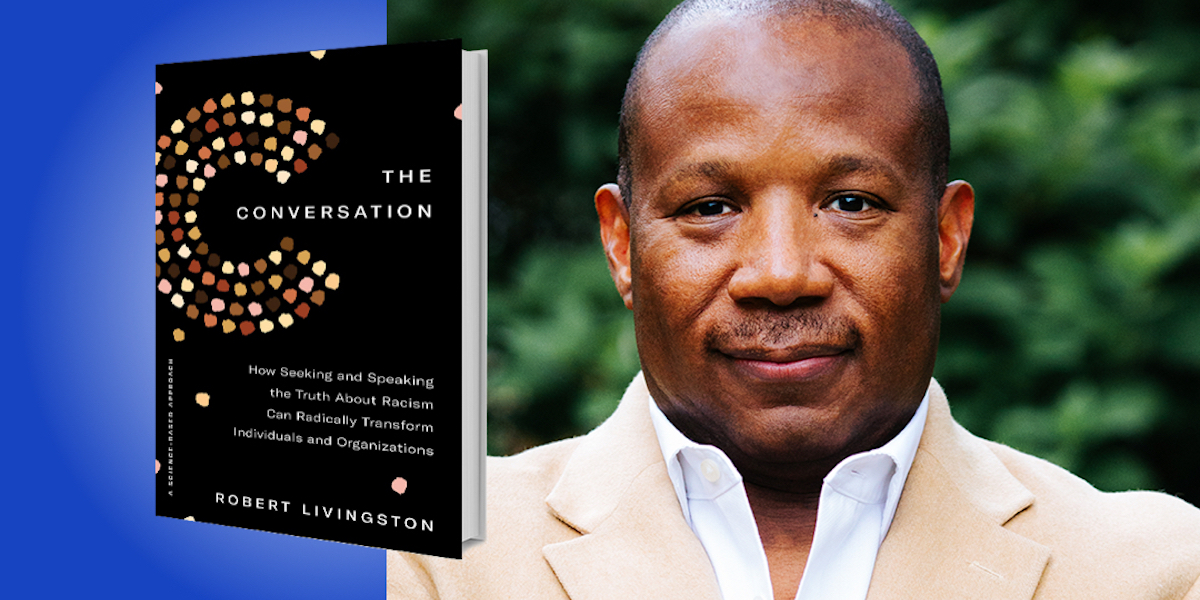

Dr. Robert Livingston is a social psychologist and one of the nation’s leading experts on the science underlying bias and racism. His research has appeared in the New York Times, the Wall Street Journal, and Harvard Business Review. For two decades, he has served as a diversity consultant to scores of Fortune 500 companies, public-sector agencies, and non-profit organizations. He currently serves on the faculty of the Harvard Kennedy School.

Below, Robert shares 5 key insights from his new book, The Conversation: How Seeking and Speaking the Truth About Racism Can Radically Transform Individuals and Organizations (available now from Amazon). Listen to the audio version—read by Robert himself—in the Next Big Idea App.

1. Problem Awareness

The solution to any problem begins with an awareness that a problem does exist. Yet not everyone agrees that racism—which is, in fact, a problem—is a real thing. There’s a lot of research and data and surveys that show that white people, on average, believe that if anything, there’s more racism against white people than against Black people. We’ve seen that manifest in many ways politically in the United States. I remember doing an engagement at an organization in Appalachia with a blue-collar group comprised of plumbers, welders, and pipefitters, who actually denied the whole notion of white privilege for a number of reasons.

Knowing that there’s a problem is necessary, but not sufficient. The next question is: What’s causing the problem?

2. Root Cause

What is the root cause of a problem? It’s an important question to investigate, not just for academic or intellectual reasons, but for practical reasons, because often knowing the root cause of a problem will inform the best solution. Here’s an example: Imagine that you are having severe headaches. So you go to the doctor, and the doctor performs a diagnosis, or a root-cause analysis. This is important because headaches can be caused by myriad factors—like stress, anxiety, and dehydration—as well as any number of diseases, including coronavirus. And so knowing what’s causing your headaches will inform the best course of treatment.

“Often problems are left unsolved not because of a lack of strategy, but because of a lack of willingness to engage and exert effort.”

The same principle applies where racism is concerned. There are three broad sources or origins of racism:

- Structural origins that are rooted in history, the legal system, and structures that are in place in society.

- Psychological origins that have to do with how our brains process information on the nature of humanity as a social species, and the fact that we form groups and have social identity (much discrimination is a function of how those identities operate).

- Situational or contextual factors, such as competition versus cooperation—or threat being present in an environment versus safety.

3. Empathy

Once you identify the problem and understand its root causes, the next question is, do you care? There’s an interesting movie that came out in the 1990s called Leaving Las Vegas starring Nicolas Cage. The movie was about the demise of an addict. He knew that he was an alcoholic, and he had some insight into what caused it and what he would need to do to fix it. But he didn’t care. He had decided to go to Las Vegas and drink himself to death; basically he told people, if you want to come and join the party, great, but don’t try to stop me. And ultimately, he does create his own demise. There just wasn’t sufficient concern about finding a solution to the problem.

Similarly, in society, there are people who may be aware of racism, but they simply don’t care, because they don’t see racism as their problem. And so one question that The Conversation focuses heavily on is: Why should everyone be concerned about racism, regardless of their race? And how can we get people to become more invested in the problem? Often problems are left unsolved not because of a lack of strategy, but because of a lack of willingness to engage and exert effort.

“Society operates much like the oval, and there are certain groups that have the inside lane by design.”

4. Strategy

I identify three broad classes of strategies for addressing racism:

- Individual-level strategies: Things that people can do to change their own hearts and minds.

- Cultural-level strategies: Things that can be done to change social norms or informal rules around what is appropriate or inappropriate, acceptable or unacceptable, what will get you praise versus what will get you scorn.

- Institutional strategies: Formal rules, laws, policies, and procedures around how people should behave.

These three different classes aren’t completely independent; in fact, they can influence one another considerably. Individuals can have an impact on the culture, for example, by confronting prejudice. When someone speaks out and says, “That wasn’t OK,” they not only change the behavior of the other individual—they send a signal to the rest of the group regarding what the cultural norms are. Similarly, when organizations change formal policies, they also change individuals’ behaviors—and this also can change cultural norms. There is a complex interplay among these three broad approaches to creating interventions around racism.

5. Sacrifice

In many ways, this is the biggest question of all: Once you know what to do, are you actually willing to do it? Is the sacrifice worth it? By implementing diversity, equity, and inclusive policies, many organizations feel that they sacrifice fairness and quality. But I argue that those are false sacrifices.

The whole concept of affirmative action, quotas, or any number of policies that have been adopted in the U.S. and around the world are sometimes seen by individuals as reverse racism, which seems unfair. But equity is our goal—not equality—and equity sometimes calls for treating people differently.

“The ‘best’ candidate is not a trait—it’s an outcome.”

Let me give you an example from my childhood: When I was about 10 years old, I went to the high school track meet of my cousin, Terry. I remember being outraged when I saw the track; it appeared that the officials had given a head start to everyone else but my cousin, who was on the inside lane. What I didn’t understand is that there is a reason that runners in a 400-meter race have a staggered start. But as a 10-year-old, I didn’t understand the geometry of circles—or ovals, in this case—and that if you gave everyone an equal starting line that it would have led to an unequal race. It would have led to an unfair outcome because the person on the inside lane actually has to run a shorter distance than the people on the outside lanes. So a staggered start wasn’t a head start at all; if they had had the exact same linear starting line, which is what I wanted them to have, then that would have created a very unfair race. I think many people don’t understand that society operates much like the oval, and there are certain groups that have the inside lane by design. So creating the staggered start doesn’t give an unfair advantage—it only gives a fair race.

The second sacrifice that organizations often assume they will have to incur is a lack of quality. Many leaders see hiring diversity as being antithetical to hiring the best candidate, as if diversity reduces quality. So let’s examine that assumption. I would argue that the best candidate is not a trait—it’s an outcome, which means that in any situation, you can never know who the best candidate is. Assuming that there is a best candidate in theory, you can never know who that person is.

In horse racing, it’s rare for any one horse to win all three races of the Triple Crown. Usually what happens is you’ve got a cluster of horses that are pretty much interchangeable. One horse will win on one day, one horse will win the next day, one horse will win the next day. Every once in a while, once a century, you’ll have a horse that’s unbeatable, like Man o’ War. But those are truly legends. Most of the time what you end up having are a lot of horses that are really good, but who ends up being the best is random. There is no “the best”—you just have a bunch of really, really good horses. That is the whole notion of statistical banding first presented by Sheldon Zedeck. So what you want to do is set a high threshold, and then treat everyone above that threshold as being interchangeable. Then you can look for diversity traits without sacrificing quality.

To listen to the audio version read by Robert Livingston, download the Next Big Idea App today: