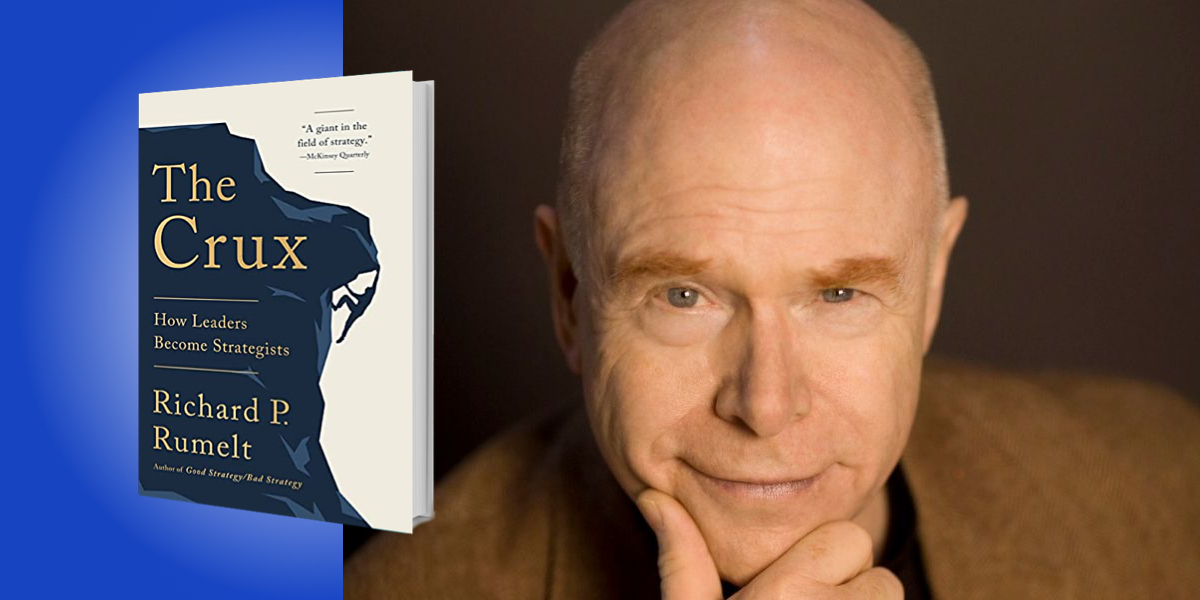

Richard Rumelt is the Harry and Elsa Kunin Emeritus Professor of Business & Society at the University of California, Los Angeles Anderson School of Management. Prior to UCLA, he worked as a systems engineer for Jet Propulsion Laboratories and was a faculty member at Harvard Business School. Rumelt’s research has focused on corporate diversification strategy, individual business strategy, and, most recently, the forces shaping industry transitions.

Below, Richard shares 5 key insights from his new book, The Crux: How Leaders Become Strategists. Listen to the audio version—read by Richard himself—in the Next Big Idea App.

1. Strategy is problem-solving.

The terrible truth about strategy is its rarity. Company after company will claim that they have a strategy, but all they really have are ambitions and financial goals. A government agency will claim that it has a strategy, but it is actually a long list of priorities which gloss over the internecine administrative struggle for resources and power.

The essence of strategy is a design of policy and action aimed at resolving a high-stakes challenge. By “challenge,” I include opportunities that may be difficult to grasp. If you don’t identify the nature and structure of your challenge, then you cannot surmount that challenge—meaning, you cannot have a strategy. Strategy is a form of problem-solving and to do good strategy work you have to put aside the language of goals and ambitions and instead concentrate on the changes and challenges that block your way forward.

2. Strategy requires insight.

Most serious strategy problems are gnarly. That is, there is no clear definition of the problem and its structure. There is no simple list of alternative actions—they have to be created—and the connections between potential actions and possible outcomes are fuzzy, at best. When we study a challenge, we should look for its central paradox, the core of what makes it difficult, the tension which might allow us to move to a solution, if resolved.

“When we study a challenge, we should look for its central paradox, the core of what makes it difficult, the tension which might allow us to move to a solution, if resolved.”

An example is Elon Musk’s solution to the long-standing problem of rocket reusability. After a failed attempt to buy a Russian launch vehicle in 2001, he began to study why rockets were so expensive. He realized that the problem was the high-heat generated by re-entering the atmosphere which destroys key components of the rocket. One solution, he hypothesized, would be carrying more fuel (fuel is cheaper than rockets) and using that extra fuel to slow the rocket’s return to Earth, having it softly land on its tail. This insight was the birth of SpaceX, which has made putting a pound into orbit 25 to 40 times less expensive than the old Space Shuttle.

3. Find the crux.

The essence of strategy is a concentration of effort, resources, and/or force if the opportunity is great or the opponent is weak. Without that concentration, there may be little gained. To gain that concentration, organizations must focus their efforts on only one or two critical challenges. When you try achieving too many things at once, policies and activities proliferate that work against each other—friendly-fire—that reduces overall effectiveness.

The crux challenge is the most critical, but also realistically addressable, problem. Wasting effort on the unimportant or unsolvable is a luxury of politicians, not strategists.

“When you identify a critical challenge (or opportunity) that can be surmounted, you have found the crux.”

To find the crux, first look at the broad array of challenges and examine potential ways to solve each of them. This will bring you face-to-face with the fact that you lack the resources to tackle them all at once. Also, it will be evident that many of the proposed actions are inconsistent, proving that the solutions themselves would fight against one another. When you identify a critical challenge (or opportunity) that can be surmounted, you have found the crux.

As a simple example: discussions of national security in the U.S. are generally about the force structure and are precursors to budgeting. Yet, the crux security challenge is probably its dependence on a peer competitor for critical supplies, including lithium batteries, solar panels, pharmaceuticals, and electronic components.

4. Strategy is a journey.

There is a common view that strategy is a long-term sketch of intent and competitive position. This erroneously makes it into something framed on the wall and written, without change, on the first page of the 10-K report each year. This mindset is damaging. It defines strategy so broadly that it is almost meaningless. It turns “strategy” workshops into financial goal-setting exercises. It imagines strategy as a commitment to a way of doing things, limiting agility. It turns the senior executives (who should be thinking entrepreneurially) into managers who try using carrots and sticks to “control” the company’s results.

“Strategy is not a thing, or a paragraph on parchment that hangs on the wall. It is a journey with no fixed destination.”

The inescapable truth is that people, organizations, companies, countries, and even civilizations, face a continuing sequence of challenges. There can be no one approach, or “strategy,” for dealing with them all.

The solution is realizing that strategy is not a thing, or a paragraph on parchment that hangs on the wall. It is a journey with no fixed destination. It is the process of dealing with critical challenges and deciding which consequential actions to take. Some challenges are long-term and broad in scope. Others are immediate blockages, or sudden opportunities, encountered on the way forward.

5. Don’t get distracted.

The enemy of effective strategy in companies is the 90-day derby: the cycle of quarterly earnings forecasts and revelations. If leadership thinks that the purpose of the company is to generate predictable, smooth earnings results, then you are being led astray. The economy is rife with uncertainty and no one can achieve “smooth” quarterly results without cooking the books. Strategy is not about always hitting the numbers. It is about solving critical challenges.

In the public sphere, the equivalent distraction is the 24-hour news cycle. National strategy is not about how the New York Times or CNN reports on policies and leaks. It is about the critical challenges facing the nation.

To listen to the audio version read by author Richard Rumelt, download the Next Big Idea App today: