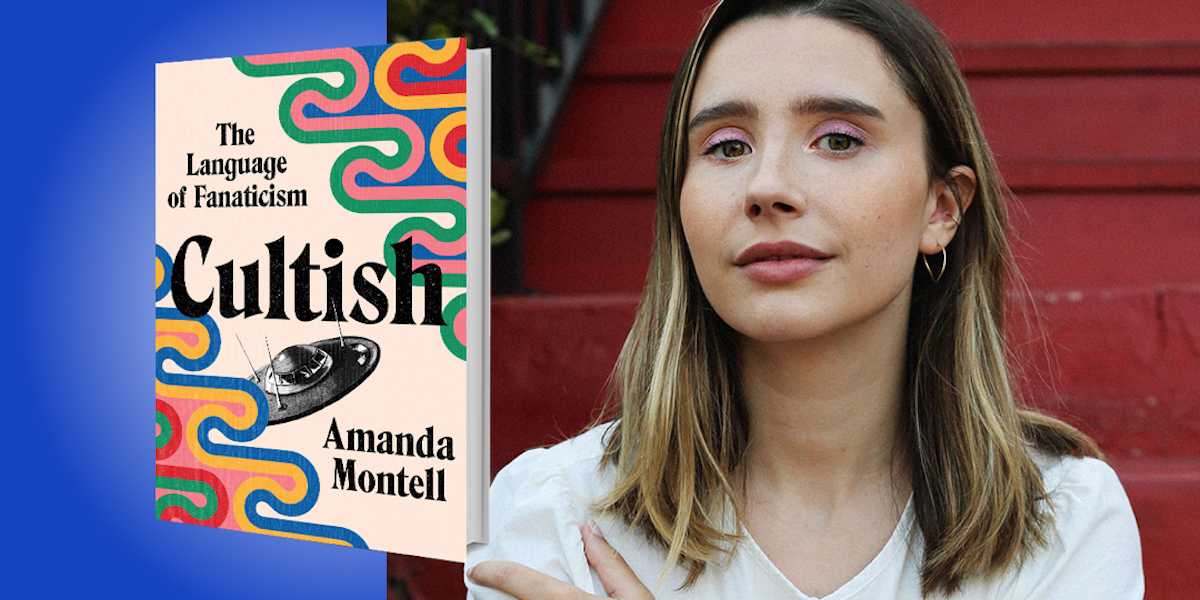

Amanda Montell is a writer, reporter, and linguist. Her first book, Wordslut: A Feminist Guide to Taking Back the English Language was published in 2019.

Below, Amanda shares 5 key insights from her new book, Cultish: The Language of Fanaticism (available now from Amazon). Listen to the audio version—read by Amanda herself—in the Next Big Idea App.

1. Brainwashing is a myth.

Why do people join cults? Why do they stay? The explanation that prevailing wisdom and the popular media gives is actually pretty flimsy—mostly just vague talk of “brainwashing.” But brainwashing is nothing but a metaphor. It is not a scientific or testable phenomenon—it’s really just a subjective judgement value that often works to morally divide us: “You’re brainwashed.” “No YOU’RE brainwashed!”

When tossed around to describe everyone from a political candidate’s supporters to militant vegans, the term “brainwashing” acquires a sort of armchair-therapist éclat. We all love a chance to feel psychologically and morally superior without having to think about why, and calling a whole bunch of people “brainwashed cult followers” does just that. The trouble is that the minute you say someone is “brainwashed,” the conversation ends there. No room is left to explore what might actually be motivating the person’s behavior—which, as it turns out, is a much more interesting question.

“We all love a chance to feel psychologically and morally superior without having to think about why.”

2. There is no objective definition of the word “cult.”

You might think of “cults” as sinister by definition, but scholars have never been able to agree on one singular list of criteria distinguishing a “cult” from a religion or another kind of tightly bound social group. In fact, many experts avoid the cult label altogether because it has so frequently been used as a pejorative, to trash religions that society just doesn’t approve of. So many of today’s longest-standing religions (Catholics, Baptists, Mormons, and most Native American religions, to name a few) were once considered unholy blasphemies in the United States—and this was a nation founded on religious freedom. Throughout history and the whole world, cultural normativity has much to do with a religious group’s perceived legitimacy, no matter if its teachings are any weirder or more harmful than a better-established group. As the religion scholar Reza Aslan famously stated, “The biggest joke in religious studies is that cult + time = religion.”

Interestingly, though, the word “cult” didn’t always boast such negative undertones. The earliest version of the term “cult” can be found in writings from the 1600s, when it simply meant “homage paid to divinity,” or offerings made to win over the gods. The word evolved in the early 19th century, a time of experimental religious brouhaha in the United States. Back then, “cult” served as a sort of churchly classification, alongside “religion” and “sect,” and it denoted something new or unorthodox, but not necessarily nefarious.

“Cult” didn’t gain its darker reputation until the mid-20th century, which, like now, was a peak cult era in the U.S. In the 60s and 70s, the emergence of new spiritual groups, from Jews for Jesus to the Church of Aphrodite, spooked old-school conservatives and Christians. “Cults” soon became associated with quacks and heretical kooks, but they still weren’t considered a major societal threat—until the Manson Family murders of 1969, followed by the Jonestown massacre of 1978. Those events put “cult” on the map as something everyone should fear.

“The biggest joke in religious studies is that cult + time = religion.”

But then, as soon as cults became frightening, they also became cool. Pretty quickly, positive uses of the word like “cult film” and “cult classic” emerged. Nowadays, the word “cult” can mean pretty much anything—someone could apply it to a new religion, a group of online radicals, or a makeup brand. This is because the fascinating history of the word “cult” corresponds to our society’s ever-changing relationship to spirituality, community, meaning, and identity—and that relationship has gotten pretty weird. Over the decades, as our sources of connection and existential purpose have shifted due to phenomena like social media and withdrawal from traditional religion, we’ve seen the rise of many alternative subgroups—some dangerous, some not so much. “Cult” has come to describe them all.

Now, in an attempt to find a less judge-y way to discuss these communities, some scholars have come up with labels like “new religious movements” or “marginalized religions.” But while these phrases work in an academic context, I find they don’t quite capture the fanatical fitness studios, multilevel marketing companies, life-consuming start-up jobs, and other everyday “cults” to which we all belong. That’s why I like the word “cultish.”

3. Language is a cult leader’s ultimate power tool.

From the crafty redefinition of existing words (and the invention of new ones) to powerful euphemisms, secret codes, re-namings, buzzwords, chants and mantras, “speaking in tongues,” forced silence, and even hashtags, language is the key means by which all degrees of cultlike influence occur. In both positive ways and shadowy ones, “cult language” is, in fact, something we hear and are swayed by every single day. Our speech in regular life—at work, in spin class, on Instagram—is evidence of our varying degrees of “cult” membership. You just have to know what to listen for.

“As our sources of connection and existential purpose have shifted due to phenomena like social media and withdrawal from traditional religion, we’ve seen the rise of many alternative subgroups.”

Language is what empowers cult leaders to create a mini universe—a system of values and truths—and then compel their followers to heed its rules. John E. Joseph, a professor of applied linguistics at the University of Edinburgh, wrote to me from Scotland, “Without language, there are no beliefs, ideology, or religion. These concepts require a language as a condition of their existence.” In other words, without language, there are no “cults.” And though “cult language” comes in different varieties, different “dialects,” if you will, all charismatic leaders—from Jim Jones to Jeff Bezos to SoulCycle instructors—use the same basic linguistic tools, a language of fanaticism I call “Cultish” (like English, Spanish or Swedish). Once you understand what the language of Cultish sounds like, you won’t be able to unhear it.

4. The “type” of person most likely to join a cult is not who you might think.

The stereotype is that those who wind up in cults like the Moonies or NXIVM are desperate, disturbed, or intellectually deficient. We tend to believe this stereotype, because out of self-protection, we want to think that there’s no way we would end up in a group like that. But what I found talking to dozens of cult survivors and scholars is that the folks who wound up in history’s most notorious cults were incredibly bright, open-minded, and service-oriented. If anything, their Achilles’ heel was not desperation, but an excess of idealism. These were the sorts of folks who believed that an answer to the world’s most urgent problems was out there, and that they could play a part in it. And when things got tough, they were willing to stick it out.

“The folks who wound up in history’s most notorious cults were incredibly bright, open-minded, and service-oriented.”

Now, this doesn’t mean that just anyone could wind up neck-deep in a cult like Jonestown, but for those who do, it isn’t foolishness that keeps them there; it’s optimism bias, confirmation bias, sunk cost fallacy—ingrained human reasoning flaws that we all possess, and that can be triggered with certain language techniques.

5. I wrote this book for my dad.

I grew up enraptured by fanatical fringe groups and their beliefs, in part because of my dad: As a teenager, he was forced to join a cult. In 1969, when my dad, Craig Montell, was fourteen, his absentee, card-carrying Communist father and stepmother decided they wanted in on the blossoming countercultural movement. So they moved young Craig and his two toddler-age half-sisters into a remote Socialist commune outside San Francisco called “Synanon.” I cut my teeth on riveting Synanon tales from my dad, who escaped at seventeen and went on to become a prolific neuroscientist.

My dad was always so generous with his storytelling, repeating the same stories of Synanon’s dismal living quarters, of the ritualistic Synanon “Game” (more on that in the book), and of course, the special language they used in Synanon to build solidarity, squash independent thinking, obscure truths, encourage us/them dichotomies, and emotionally charge experiences such that no other way of life seemed possible. It was my dad who instilled in me my sense of skepticism, but also my intense enthusiasm and curiosity, and my love of storytelling. I dedicated this book to him.

To listen to the audio version read by Amanda Montell, download the Next Big Idea App today: