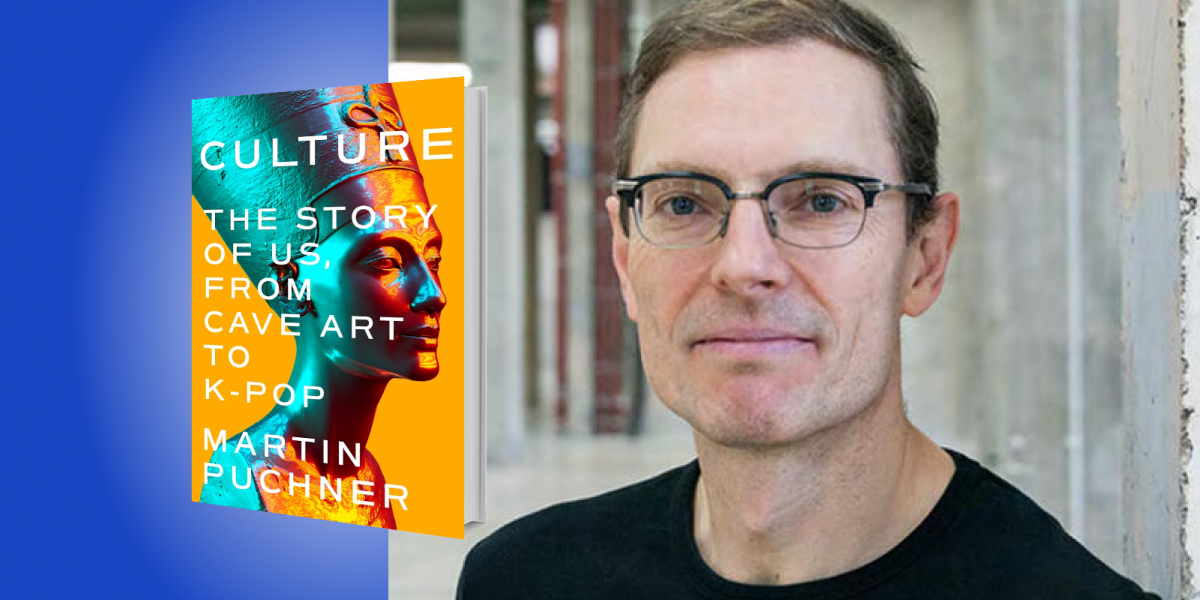

Martin Puchner is a literary critic and philosopher who teaches in the English Department at Harvard University and offers free online courses at HarvardX. He is also a global fellow at the University of London. He is editor of the Norton Anthology of World Literature, which has been read by millions of high school and college students since its first publication.

Below, Martin shares 5 key insights from his new book, Culture: The Story of Us, from Cave Art to K-Pop. Listen to the audio version—read by Martin himself—in the Next Big Idea App.

1. Culture is not natural.

Humans have produced culture wherever we lived, but the stories, paintings, and performances produced don’t last. Unlike in biological evolution, we don’t automatically pass these creations down to the next generation through our genes. Therefore, we need storage devices to preserve culture for the future. The earliest such storage device were prehistoric caves. In the Chauvet cave in southern France, humans decorated the rough surfaces with dozens of paintings 37,000 years ago and continued this work for thousands of years, across two hundred generations.

Humans never used the Chauvet cave for shelter. They went there only to express how they saw their place in the universe through painting—not know-how (the technical and scientific knowledge humans accumulate), but know-why (the human quest for meaning).

Fortunately, the Chauvet cave not only gave rise to this work but also preserved it for the future. A similar role as storage devices was later played by temples, theaters, libraries, and all the way to today’s electronic media. They are all places where culture is made, preserved, and passed down to the next generation.

We need to invest in such places of art making and storage so that we can continue the work our predecessors have wrought. Culture needs our constant and active engagement. Otherwise, it will disappear.

2. We are all latecomers.

We often focus on firsts: which culture first invented casting in metal; who first came up with the idea of writing; or when printing with movable type was first invented. Being first is seen as a matter of pride and prestige. But often, that focus on firsts is misplaced. Especially in the arts, there was always someone who was there before us, and whose ideas, beliefs, and art works we must reckon with.

Let’s return to the Chauvet cave. After humans had labored in them for thousands of years, a landslide sealed off the entrance, and no one could enter anymore. Then, a few thousand years later, another landslide opened the entrance for a short while before it was closed off again for the next thirty thousand years, until the late twentieth century.

“Whenever we go to archeological sites, visit a museum, or read an older text, we are confronted with the artistic expressions of distant predecessors, trying desperately to understand what they mean.”

Now imagine a second group of humans entering the cave during that short interval. By the light of their flickering torches, they would behold the stunning work that had been done thousands of years earlier. Most likely, that second group had no connection to the original artists; after all, they were separated from them by as much time as the Roman Empire is from us. And yet this second group tried to make sense of the strange paintings, remnants of an alien culture. They didn’t just admire these works, they made them their own by continuing the work on the cave in their own distinct style.

We’re like this second group of artists. Whenever we go to archeological sites, visit a museum, or read an older text, we are confronted with the artistic expressions of distant predecessors, trying desperately to understand what they mean. Inevitably, we relate these strange works to our own world and try to incorporate them into our own lives.

Embracing our status as latecomers can instill a certain awe at the creativity and ingenuity of previous generations. But it can also give us the freedom to use and adapt what others have created for our own purposes. What matters in art is not who was first, but how we latecomers use what has come down to us in new ways.

3. Cultures thrive by borrowing.

There is a view of culture that focuses on distinct traditions created by tightly knit communities, who defend their tradition against outside interference. But once you look more closely into these traditions, you realize that they are made of fragments borrowed from others. This is because cultures thrive by borrowing. Borrowing from the past and from other cultures gives artists new ideas, shows them new possibilities, and thus leads to richer forms of expression that are more likely to endure over time.

My favorite example is Pompeii. When the volcano Vesuvius erupted in 79 of the Common Era, it buried the city under a thick layer of ash, essentially creating a time capsule, a snapshot of life in the Roman Empire. Among the items found in the city was a small statue from South Asia representing a goddess. Its very existence in Pompeii shows how much trade the Roman Empire did with the east; Romans imported not just art but also silk and spices. They imported so much that they created a trade imbalance with the east.

“Borrowing from the past and from other cultures gives artists new ideas, shows them new possibilities, and thus leads to richer forms of expression that are more likely to endure over time.”

What did the new owners make of this statue? Most likely they mistook her for a representation of the Roman goddess Venus. These kinds of misunderstandings are often the byproduct of borrowing.

But the borrowing doesn’t stop there. The Roman Goddess Venus was herself adapted from Aphrodite, whom Romans had decided to borrow from their one-time foe, Greece. Today, we think of the progression from Greece to Rome as natural, as if the baton of culture was passed from the one culture to the next. But the truth is much stranger. What happened between Rome and Greece was a cultural graft, with one culture, Rome, deciding to graft the art of another culture onto its own tradition.

It wasn’t just Rome. All cultures are made from borrowed figures, gods, and artworks. And that’s not a bad thing. It’s what makes cultures grow in new ways.

4. Nobody owns culture.

In our current debates about culture, we worry a lot about appropriation, about facile or disrespectful uses of other cultures. I sympathize with the goal of being respectful, but I worry about the assumption that any culture can be someone’s exclusive property.

My favorite example is the Kebra Nagast, the scribal text of ancient Ethiopia and its protagonist, the Queen of Sheba. Now, the Old Testament describes how she visited King Solomon in Jerusalem, to see whether he really was as wise as his reputation suggested. According to the Kebra Nagast, the Queen of Sheba not only visited King Solomon but also became pregnant with a son before returning home. When the son comes of age, she sends him to his father, who accepts him as his heir. But before long, the son wants to return to Ethiopia. Before he and his companions depart, they steal the Ten Commandments and take them to Aksum, the capital of Ethiopia. In other words, the Kebra Nagast uses the Queen of Sheba episode from the Old Testament for its own purposes, to claim descent from the legendary King Solomon, and adds to this story the outright theft of the Ten Commandments, which then become the cornerstone of Ethiopian Christianity.

“This story of the union of King Solomon and the Queen of Sheba and of the Ten Commandments shows just how little sense it makes to think of culture as the property of one group.”

The theft is, of course, imaginary. There is no evidence that it ever happened (although it is true that the original Ten Commandments disappeared from Jerusalem at some point). I do think that precious objects that were stolen and are now housed in museums should be returned, but this story of the union of King Solomon and the Queen of Sheba and of the Ten Commandments shows just how little sense it makes to think of culture as the property of one group. No one owns culture; it’s by incorporating the achievements of others that we make them our own.

5. Be humble.

The upshot of the preceding four insights is that they all lead to an attitude of humility. The heroes of this book treat the ideas of distant places with respect and curiosity even when those ideas challenge their most deeply held values and convictions. Translators working in the House of Wisdom in medieval Baghdad studied Greek philosophy, even though it might challenge Islam; some Christian nuns and monks working away in Medieval monasteries, such as the one founded by Hildegard of Bingen, kept alive pre-Christian writing even though it could challenge Christianity.

We, who are living in a very judgmental age, can learn from these figures. They knew that their own values and beliefs would not last, and they trusted that the future would not judge them too harshly. Will our own convictions fare better? I doubt it. This means that we should treat the past, even if we don’t always approve of it, with as much humility as we hope that the future will treat us.

To listen to the audio version read by author Martin Puchner, download the Next Big Idea App today: