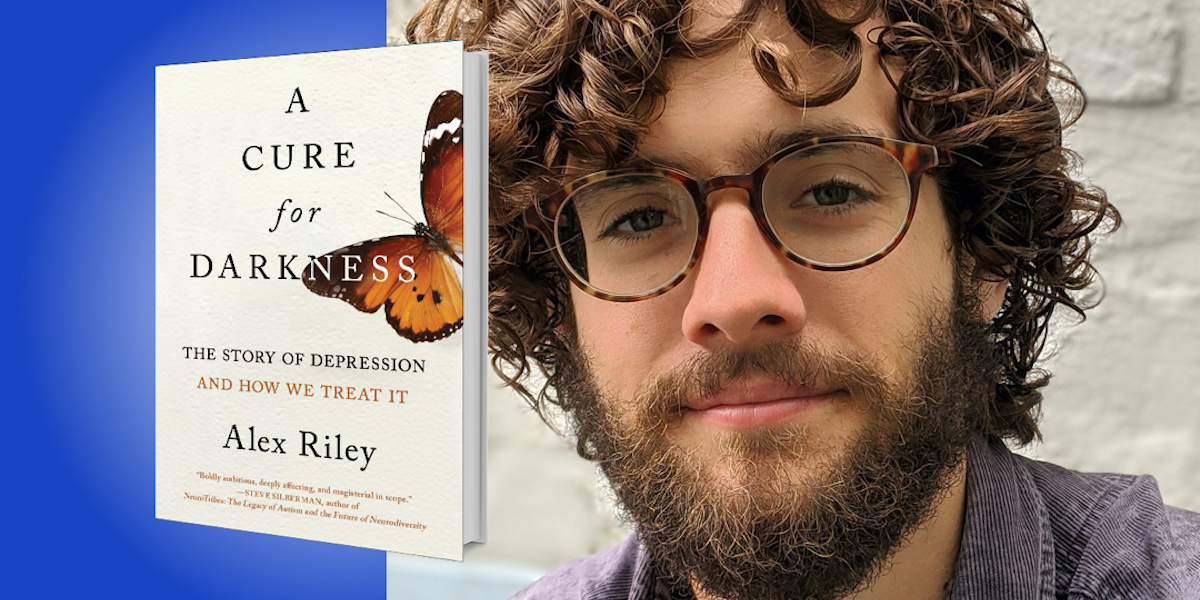

Alex Riley received a best feature award from the Association of British Science Writers for his reporting on The Friendship Bench, a project that began in Zimbabwe in 2006 and has since provided mental health care to thousands of people in New York. A former research scientist, he has co-authored peer-reviewed scientific papers while working at the Natural History Museum in London. Since leaving academia in 2015, he began writing popular science articles for magazines such as New Scientist, PBS’s NOVA Next, BBC Future, Mosaic Science, Aeon, and Nautilus Magazine.

Below, Alex shares 5 key insights from his new book, A Cure for Darkness: The Story of Depression and How We Treat It (available now from Amazon). Listen to the audio version—read by Alex himself—in the Next Big Idea App.

1. The word “depression” hides a diversity of experiences and disorders.

Depression can describe anything from low mood to a severe, life-threatening illness that requires aggressive forms of therapy. Some people might have trouble with an unshakable low mood, while others might believe that their insides are rotten, and that their only true path is to kill themselves. These aren’t just different ends of a spectrum, but are discrete experiences that have little in common other than the word “depression.”

In fact, two people with depression can show symptoms that aren’t only different, but complete opposites. There are those who sleep over ten hours a day, eat so much that they gain a lot of weight, and constantly feel fearful or anxious. Then there are people who can’t sleep more than a few hours, lose so much weight that they are at risk of starving, and feel numb to much anxiety. Both of these people can be labelled as “depressed” but that can overlook their very different symptom profiles and the potential treatments.

Once we recognize this diversity of depression, we see why there is such a wide range of treatments. Some people might require exercise or psychotherapy, others may need antidepressants, and still others could benefit from antipsychotics or electroconvulsive therapy. There is no one-size-fits-all solution, because there are many sizes of depression.

“Two people with depression can show symptoms that aren’t only different, but complete opposites.”

2. Psychiatry shouldn’t leave its successes behind.

Out of all medical professions, I think psychiatry is the most desperate to forget about its past. With crowded mental asylums, restraints, lobotomies, and a range of shock therapies in its recent history, this isn’t surprising. But effective treatments can be lost in the rush for progress. One example is the earliest type of antidepressants: MAO inhibitors. Found to have some potentially life-threatening side-effects with certain fermented foodstuffs, these drugs have been labeled as dangerous ever since. Even though the risk of complications is incredibly low, they aren’t often prescribed. Psychiatrists are hesitant to make use of an effective treatment due to the baggage of the past, and this is a shame knowing that MAO inhibitors are very effective in forms of depression that come with overeating, oversleeping, and high levels of anxiety or phobias.

Then there’s electroconvulsive therapy, or ECT. First used in Italy in 1938, it was a horrendous treatment that broke bones, sapped oxygen from the brain, and could leave people in a worse mental state than before their treatment. But in a world without antidepressants, it was a miracle to see some people with the most severe forms of depression improve in a matter of days. Over the ensuing decades, it was refined and made safer with modern machinery, muscle relaxants, and general anesthetic. Today’s ECT patients prefer it to the atypical antipsychotics that can play havoc with their metabolism and damage their heart. ECT is a remarkable treatment, and psychiatry should welcome it back in its modern form for the most severe mental illnesses. With psychotherapy and medication, it can mean the difference between life and death.

3. Exercise and diet should be routine parts of mental health care.

When I was desperate to find something that could stabilize my mood, I found a long history of using exercise and changes in diet. In some of the oldest texts of ancient India and Greece, the importance of a healthy lifestyle in our mental well-being was obvious, and was prescribed to those suffering from what is now known as depression.

“In a reversal of history, mental health care in Western countries is now being guided by successes in sub-Saharan Africa.”

I think we have forgotten this important lesson from history, instead becoming fixated on medication and psychotherapy. While both can be effective and are an important addition to the treatment of depression, I think they should always be combined with regular exercise and a healthy diet. In fact, these lifestyle changes can have an efficacy similar to first-line treatments such as selective serotonin-reuptake inhibitors (SSRIs) or CBT.

But how does someone with depression have the motivation to exercise or cook delicious meals? Well during a depression, they probably can’t. So I think it’s best used as a preventative approach, rather than a treatment.

4. Depression isn’t a Westernized disease or a product of civilization.

For much of the 19th and 20th centuries, colonial psychiatrists were so adamant that depression was a Westernized disease that they failed to detect its obvious symptoms in the African and Asian people they saw every day. Only when psychiatrists reached into communities in Uganda, Nigeria, and Zimbabwe, spoke the indigenous language, and gained the trust of the locals did they realize that depression wasn’t just present—it was more common in these low-income, often rural, settings. Using local idioms for distress—such as “thinking too much” or “heart pain”—the reality of depression was revealed and could be treated.

Instead of being a product of civilization, depression often takes root in poverty, in the wake of trauma, and in areas affected by infectious disease, famine, civil war, and high infant mortality. In 2018, I traveled to Zimbabwe to meet a group of grandmothers who were trained to provide evidence-based psychotherapy to their neighborhood. Sitting on a wooden bench under the shade of a leafy tree, they provide counsel to their clients about their problems back home, whether they be domestic abuse, HIV, or unemployment.

“These studies aren’t showing us anything new—they’re just translating millennia of knowledge into the modern language of science.”

Such community health care is now being used around the world, even in high-income countries such as the United States. In New York, I met with a peer supervisor named Helen Skipper who is training community health care workers to reach into underserved communities and tackle the same problems found in Zimbabwe: infectious diseases such as COVID-19, record levels of unemployment, and an epidemic of opioid addiction. In a reversal of history, mental health care in Western countries is now being guided by successes in sub-Saharan Africa, a place where, only a few decades ago, it was assumed that depression didn’t even exist.

5. Psychedelics aren’t new treatments—they have been used for thousands of years.

Psychedelic drugs like psilocybin (the active molecule in magic mushrooms) and DMT are in vogue right now, being used to treat drug addiction, anxiety in cancer patients, and depressions that haven’t responded to at least two different types of antidepressants. What I find most compelling about these substances is that they have been used for thousands of years—and in the heart of the Amazon rainforest, their specific purpose was for healing.

Ayahuasca is a tea composed of Amazonian plants that contain two psychoactive substances: a psychedelic, and something that prevents this first substance from being broken down in the brain. It leads to a lot of nausea, gastrointestinal distress, and eight hours of intense hallucinations, including colors, animals, and sometimes a deity known as “Mother Aya.” It is described as “labor” rather than a “trip.” In my book, I chose to cover the work of Brazilian researchers because they use placebo-controlled trials, which include fake ayahuasca-like drinks. One particular highlight was the 60-year-old retired fisherman who was given the fake drink, but believed he had been given the real thing. As a result, he had an epiphany: His ten-year depression could be tackled by returning to the ocean, the place where he is most at home. Even though his drink didn’t contain a trace of a psychoactive substance, the placebo effect is a powerful force.

Psychedelics are likely to become a part of psychiatric care, but the cultural importance of these drugs should never be forgotten. As one scientist working in Brazil told me, these studies aren’t showing us anything new—they’re just translating millennia of knowledge into the modern language of science.

To listen to the audio version read by Alex Riley, download the Next Big Idea App today: