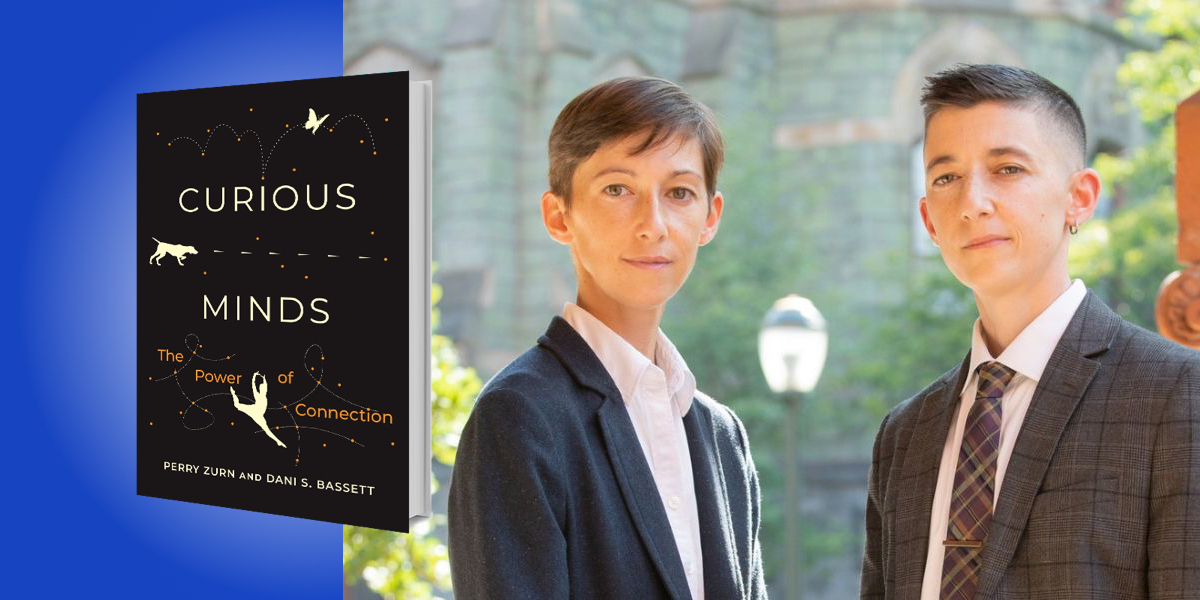

Dani S. Bassett is the J. Peter Skirkanich Professor at the University of Pennsylvania, with appointments in bioengineering, electrical and systems engineering, physics and astronomy, neurology, and psychiatry. They are also an External Faculty member of the Santa Fe Institute. Their work lies predominantly in neuroscience.

Perry Zurn is an Associate Professor of Philosophy at American University and an affiliate faculty in the Department of Critical Race, Gender, and Culture Studies. He is a political philosopher who studies how change happens in our minds, bodies, and across people and institutions.

Below, Dani and Perry share 5 key insights from their new book, Curious Minds: The Power of Connection. Listen to the audio version—read by Dani and Perry—in the Next Big Idea App.

1. P is for power.

Curiosity is an immensely powerful capacity. Humanistic and scientific research shows that curiosity is linked to the ability to innovate, to create something new or newly helpful—whether that be a new idea or widget, a new process or business, or a renewed form of social organization.

Curious people can rearrange, remodel, reorganize, and restructure. They have the capacity to be world changers by imagining a different future. Hence, curiosity can drive fundamentally big things. But curiosity can also drive small things—the little ways in which we choose to live our lives, learn about each other, or interact with our world (whether with friends and family or earthworms and bumblebees). Its power can manifest in intimate ways, just as much as in grand social gestures or scientific discoveries.

In either case, curiosity has the power to make our worlds better or worse. It can blow open possibilities for more equitable ways of being, or it can exacerbate existing inequities by continuing down a curious path that no longer serves us. Curiosity has the potential to transform our inner and outer worlds for the better.

2. O is for omnipresent.

Curiosity’s power isn’t only for the exceptionally smart—it’s for everyone. Put simply: Curiosity is everywhere and in each of us. Some people think they can divide their friends, coworkers, students, or kids into those who are and who are not curious. It is far more compelling to recognize that all of us are curious.

“Curiosity is a mark of creatures in general: we explore, experiment, and innovate.”

We propose that curiosity just is a basic element of being human (and of being more than human). Curiosity is a mark of creatures in general: we explore, experiment, and innovate. We are simply curious about different things and in different ways. Curiosity is not only the capacity to raise your hand, ask a lot of questions, or speak quickly and eagerly about your interests while maintaining earnest eye contact. This describes some of us, but certainly not all of us. Your curiosity may lead you to love math, or history, or obsess over sports trivia. Or it may lead you to practice dance, do carework for the elderly and the sick, or get knee-deep in river restoration.

Curiosity is not essentially intellectual or verbal. It can suffuse anything we do. Curiosity is the basic force by which we each build an understanding of our worlds.

3. W is for weaving.

Curiosity is a connective force that allows us to weave together thoughts and understandings, people, and entire communities. This idea is radically new in the nascent field of curiosity studies. For decades, centuries, and millennia, curiosity has broadly been conceptualized as the drive to acquire bits of information. From Thomas Aquinas and Saint Augustine to Rene Descartes and Friedrich Neitzsche, thinkers of the past have foregrounded the individual knower in such a way.

The key limitation of the acquisitional account is that it neglects how knowledge gets made. Separate, individual pieces of information are not knowledge. Rather, knowledge is a network of relations among ideas. French mathematician Henri Poincare once noted that, “Science is not things themselves, as the dogmatists in their simplicity imagine, but the relations among things; outside these relations there is no reality knowable.” Philosopher John Dewey noted more broadly that, “Knowledge is such a network of interconnections that any past experience will offer a point of advantage from which to get at the problems presented in a new experience.”

“Knowledge is a network of relations among ideas.”

If knowledge, whether in science or everyday life, is a network of relations among ideas, then curiosity is the practice of building that network, of thatching together pieces of information, and doing so alongside other knowers.

4. E is for exercise.

In Curious Minds, we excavate expansive evidence from the humanities and the sciences demonstrating that people exercise curiosity in different ways—with different styles. We discuss three common styles in depth, and then briefly mention 18 other styles that we drew from animal life as recounted in a variety of literatures. The three styles are the butterfly, the hunter, and the dancer.

The butterfly is someone who welcomes any and all kinds of information, perhaps loves trivia, and may have 100 tabs open on their computer. They connect information loosely, creating knowledge networks that span and sprawl. The hunter, by contrast, follows trails, tracks scents, and ferrets out secrets. They connect information in a purposeful, finely crafted way, thereby creating tight knowledge networks. The third style is the dancer, who takes leaps of creative imagination, creating loopy knowledge networks.

“Each style of curiosity not only pairs well with different personalities, but also lends itself to different projects.”

Curiosity styles are ways that we navigate our information-seeking. Each style of curiosity not only pairs well with different personalities, but also lends itself to different projects. Many of us are all three in different contexts, for different purposes, and even at different times of the day. Wanting to know anything about everything keeps us open. Wanting to know everything about one thing keeps us focused. And wanting to create knowledge—to put two things together that haven’t been—keeps us innovative. There are all kinds of ways to exercise curiosity.

5. R is for revolutionary.

When we realize that curiosity is the capacity to connect ideas and people, our collective approach to learning and social change has to shift. If our communities, classrooms, and workplaces are full of curious people who, nevertheless, may have radically different ways of being curious, how do we facilitate that diversity? How can we structure learning experiences so that people across the board feel equally supported to practice their curiosity in ways that enhance individual and collective flourishing? How might K-12 pedagogies need to change, for example, to equally nurture neurotypical and neuroatypical curiosity styles? How might our workplaces need to change to welcome different cultural approaches to questions?

Of course, learning isn’t confined to our schools and jobs. Learning suffuses every aspect of life. How might a connective approach to curiosity (which attends to how we put two and two together) revolutionize politics? How might an appreciation of the differences in our curiosities give us fresh ground on which to collaborate on pressing problems?

To listen to the audio version read by authors Dani Bassett and Perry Zurn, download the Next Big Idea App today: