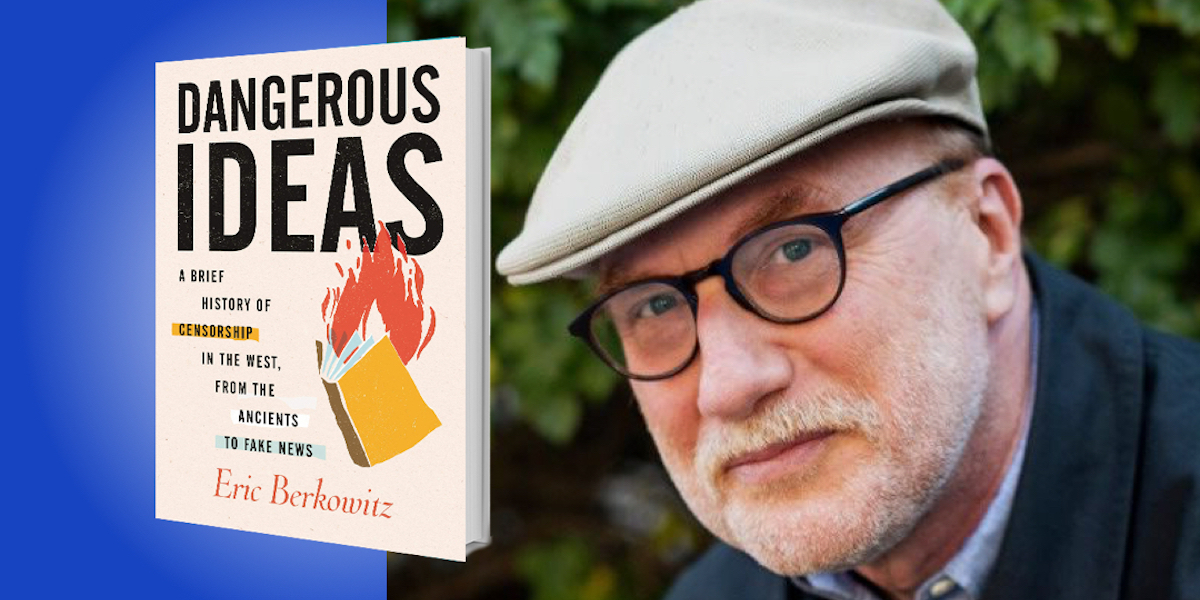

Eric Berkowitz is a San Francisco-based public interest lawyer, journalist, and writer. Much of his time is spent representing refugees from central America, Africa, and Mexico in asylum cases. His remaining availability is largely consumed by writing books.

Below, Eric shares 5 key insights from his new book, Dangerous Ideas: A Brief History of Censorship in the West, from the Ancients to Fake News (available now from Amazon). Listen to the audio version—read by Eric himself—in the Next Big Idea App.

1. Censorship doesn’t work.

A text might be burned, people might be punished or killed, but the ideas expressed persist, and often gain more currency for being forbidden fruit. This is because words, as the poet John Milton said, live apart from the pages they appear on. Once the invention of the printing press supercharged the spread of ideas to non-elites, and censorship laws birthed a massive black market, publishers told writers to write “anything that will be forbidden.” And they never stopped—France’s chief 18th-century censor admitted that those who read only approved texts were a century behind the times, and he stopped publicly burning books because doing so only spiked sales.

This is no less true now, when the diffusion of speech online makes it impossible to lock it down. China knows that its “Great Firewall” against Western news is continually circumvented—recently, a raft of forbidden news was routed through the online game Minecraft—but the government’s resolve has only hardened. Once an aggressive stance toward speech has been taken (even a symbolic one), to soften it just digs authorities into a deeper hole. Censorship is a confession by rulers that they cannot coexist with nonconforming ideas, and therefore it is always a display of weakness.

Even seemingly well-intentioned censorship backfires; prohibitions of fake news and hate speech have not reduced the hatred and falsehoods in circulation. In many cases, the rules are used to perpetuate lies—particularly about the COVID pandemic—while inadvertently punishing legitimate dissent.

“Censorship is a confession by rulers that they cannot coexist with nonconforming ideas, and therefore it is always a display of weakness.”

2. Power rests on a veneer of infallibility as much as on force, and censorship is used to protect that illusion.

We see this as early as the first Chinese emperor, who in 213 BCE destroyed Confucian and other philosophical texts he thought made him look bad. For good measure, he also buried 400 Confucian scholars alive. We’ve also seen it as recently as Donald Trump’s infantile amazement that a Saturday Night Live skit lampooning him could be “legal.”

“Authority requires a mask,” observed sociologist F.G. Bailey, to conceal its failings and shield it from contempt. Machiavelli knew this when he counseled his prince to guard his grandeur above all else. All power requires a measure of popular faith, and all faith is brittle. By 1704, England’s Lord Chief Justice pronounced that “no government can be safe” unless those who make others have an “ill opinion” of it are punished—even if what they say is true.

Machiavelli’s contemporary, Henry VIII, took matters to extremes. He imposed harsh censorship and executed people for treason when they so much as “imagined” his death, or uttered words challenging his swollen “dignity.” It got so bad that his doctors were afraid to declare him ill, lest that lead them to the executioner.

The fact that a piece of speech poses no actual threat to an authority makes no difference. China’s President Xi Jinping’s power was not jeopardized by online comparisons of his face to that of Winnie the Pooh, but that didn’t stop him from erasing Pooh from the internet. In places like China, the internet is under reasonably firm government control, unlike the United States where even monsters are granted access to the podium.

3. We’ve created online speech monsters.

Until recently, free-speech dynamics were two-sided. The censored were outliers—dissidents, heretics, artists, and nosy reporters—who were vulnerable to those with the power to jail or kill them. Gains for free speech were exacted at the expense of the power of such authorities, and in the U.S., the gains have been considerable; our government is almost helpless to curb speech. At the same time, our private freedoms allow us to act as mini-dictators over what is said in our domains.

“Every online spat, every circulating lie or conspiracy, rings ‘ka-ching’ in Mark Zuckerberg’s pockets.”

Barreling into that breach is a third set of players: internet platforms, with more raw power over speech than any dictator or pope could dream of. With virtually unchecked authority, they arrange and censor speech countless times per day, mostly with secret algorithms, and they do it for money. Every online spat, every circulating lie or conspiracy, rings “ka-ching” in Mark Zuckerberg’s pockets.

We’ve created monsters—giant entities with unprecedented censorship power, yet protected by the law as if they run small, private schools. But it gets worse. Profit-seeking corporations of all stripes are pushing this dynamic to claim “speech” rights over sales of people’s online data. This wasn’t intended when the “marketplace of ideas” concept was first developed a century ago. To address the situation would require a significant re-thinking of the First Amendment, which may well exacerbate the situation.

4. European restrictions on speech are slipping in through the side door.

Hate and offensive speech is far less protected in Europe than in the United States. Expressions of hatred and malicious lies are seen as ideas here, and all ideas are protected under the First Amendment. In Europe, such expressions are often criminalized as assaults on human dignity and promotions of intolerance. Raising the Nazi salute in Germany will get you arrested, while even cross-burning is protected speech in the States.

In their early days, social media platforms exported America’s absolutist First Amendment values abroad, but that has been reversed; under European pressure, the platforms have imported European hate speech rules under the guise of their terms of service and community standards. And they are enforcing them.

“Representations of history have always been sculpted—or falsified—to shore up power and class structures.”

None of these speech restrictions would survive a minute in an American court if they were imposed by the government, but they can’t be challenged because they are technically private. In any event, a large number of Americans are comfortable with online hate speech enforcement, and seem to want more of it. A recent poll found that about half of Americans think hate speech should be illegal, and a higher percentage of millennials believe the First Amendment is outdated and should be rewritten to reflect “the cultural norms of today.”

5. Censorship concerns the past as much as the present.

With all this talk about suppressing online communications, we forget that the past has preoccupied censors every bit as much the present. Representations of history have always been sculpted—or falsified—to shore up power and class structures, and provide people with a sense of collective destiny. As such, the past is less an accumulation of verified facts than a psychological reality. For governments, the management of that reality through censorship is aimed at protecting their authority and undermining their opponents—living and dead.

Napoleon banned the works of Roman historian Gaius Tacitus because he didn’t want descriptions of tyrannical emperors to remind French readers of him. An American filmmaker was jailed during World War I for a movie depicting British atrocities during the Revolutionary War; the judge didn’t want Americans to know how badly America’s current ally had behaved, and thought it might make Americans “a little slack” in their support of the war. Poland has a new law censoring any scholarship showing its complicity in the murder of Jews during World War II. The list goes on.

Even well-meaning censorship of history carries risks. The 1980s prosecutions of a Canadian holocaust denier for publishing the pamphlet Did Six Million Really Die? backfired spectacularly when the Canadian Supreme Court held that “unpopular ideas” were as protected as mainstream ones. Pointedly, the court reminded the citizenry that Native Canadians and African Americans were long the subject of racist slanders that were accepted and taught as fact. Freezing history into an “acceptable” narrative, the Court held, is inconsistent with free speech.

To listen to the audio version read by Eric Berkowitz, download the Next Big Idea App today: