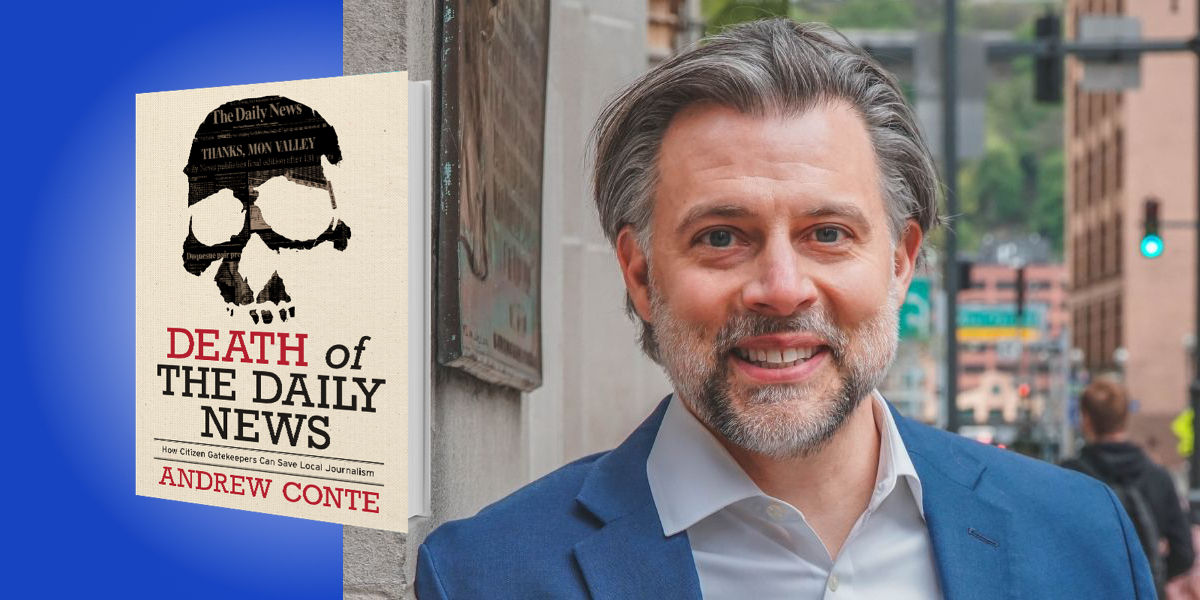

Andrew Conte is a former investigative journalist and the founder of the Center for Media Innovation at Point Park University in Pittsburgh, which serves as a laboratory for the present and future of local journalism.

Below, Andrew shares 5 key insights from his new book, Death of the Daily News: How Citizen Gatekeepers Can Save Local Journalism. Listen to the audio version—read by Andrew himself—in the Next Big Idea App.

1. Disruption causes unbelievable heartache – but it also creates unimaginable opportunities.

It hurts to see friends lose their jobs, to see beloved institutions fade away, and to see our communities mired in misinformation and deliberate disinformation. At the same time, we’re living in the most exciting communications revolution since Guttenberg and his printing press.

Since losing its newspaper, McKeesport, Pennsylvania has seen an explosion of activity by citizen gatekeepers, who are now choosing what information to share with their family, friends, and others around them. First, people start asking questions like, “What do you know?” or “What have you heard?” Then, they turn to social media. More than 65 Facebook pages exist throughout the Mon Valley, including a half-dozen focused on news and one actually called The Daily News.

In addition, an online news outlet run by a former journalist with local journalists continues to grow more robust. Four businessmen in a nearby community started their own printed newspaper and hired a reporter in McKeesport. The Center for Media Innovation has also started a community newsroom in the Mon Valley. It is run by Martha Rial, a Pulitzer Prize-winning photographer. We work with young people in middle school and with people in their 70s and 80s.

The idea of news deserts is a misnomer because the news keeps happening. People just have to figure out how to understand it. We’re seeing a new pattern play out, from small towns to big cities. When large, traditional news outlets shrink their coverage areas, lay off reporters, or simply close, citizens start doing the work of sifting through all the available information and making sense of it. They rarely consider themselves to be journalists, and yet these people are providing valuable resources to the places where they live.

“The idea of news deserts is a misnomer because the news keeps happening.”

They also tend to bring new perspectives to local storytelling. In the past, a few wealthy people controlled the narrative of local news because they could afford a printing press or broadcast license. Thanks to affordable technology, all sorts of people now have this ability—and they’re using it. We have tended to look at news deserts from a deficit narrative, but by flipping the script, we can start to value the many positives that exist too.

2. People value local news more than they think.

When The Daily News closed, some local politicians rejoiced: No one would be asking them difficult questions any longer. They quickly realized, however, that no one would be telling the positive stories about them either.

Newspapers create what community engagement experts call “social capital,” the value that builds up when neighbors interact and learn about each other. Newspapers tell our stories from birth to death and everything in between. Many people remember the first time their name or photo appeared in the paper. People often read the same newspaper as their parents and grandparents and even great-grandparents. As newspapers disappear, many residents can feel lost.

In its wake, people have started trying on their own to fill in the gaps—with mixed success. In Mon Valley, they share reliable information but it gets mixed with rumors, made-up stories, and personal opinions. For example, one story recounts how one person shared on Facebook that a police officer had been shot. Another person said they “confirmed” the story by driving past the hospital and seeing a bunch of police cars. Any journalist knows that kind of anecdote does not mean anything without actual verification. To social media users, it can seem to mean everything. When an actual police officer tried to correct the story to say no one had been shot, people refused to believe the truth. We need to value reliable local news in places where we still have it.

3. Social media matters.

All the ways that we share information matter. We often act like we can say anything on the internet because it just floats away somewhere. In reality, these exchanges—the information we share—make up our community conversations. They define what we know about the places where we live.

The term “citizen gatekeepers” hearkens back to a media study from the 1950s, in which a Boston University social scientist looked at a mid-sized newspaper in a Midwestern town. A single night wire copy editor made decisions about what information would go into the newspaper from all the available sources. This particular person did not care for Catholics and kept out stories about the Vatican, he favored conservative perspectives in every case, and avoided certain stories such as salacious murders and suicides. In the pre-internet age, one person could serve as a gatekeeper to information for their community.

“Today, we all serve as gatekeepers to information for the people around us.”

This underscores the importance of publications such as the Chicago Defender and the Pittsburgh Courier, which had bureaus and distribution via railcar across the country. If you were a Black person for much of the 20th Century, you had to rely on local white journalists to tell you about the Civil Rights Movement and African-American culture, unless you could get a copy of these newspapers. Today, we all serve as gatekeepers to information for the people around us. Without thinking, we make decisions all the time about what to tell our neighbors and what to share on social media. I’m calling on us to take these moments more seriously.

4. Once we acknowledge that information matters, we must do a better job of protecting it.

Reflect on the Peter Parker Principle, from Spider-Man: “With great power, comes great responsibility.” We’ve all been given the power to publish and broadcast from our cell phones and laptop computers, and we need to take responsibility for what we share.

Di’s Kornerstone Café in McKeesport is a place where a lot of residents turn for information because so many people eat there, including police officers, politicians, firefighters, etc. Diane Elias, who owns the shop, ran for school board and got elected basically on the strength of her restaurant. On a typical day, someone will come in or call with a question about something they’ve heard. Di and the waitresses will work like detectives piecing together the story by calling people they know and chatting with the diners.

It does not always go so well. Di tells the story of how people around town were saying that a local businessman named Ray had died, and it seemed true—until one day when he walked into the café. He was alive. He was a good sport about the rumor, but it underscored the need to confirm local news. Now, Di said she shares only information that she can confirm with primary sources. Each of us needs to start a little revolution by only sharing information that we have confirmed and know to be true.

5. Journalists can expand their reach by working with the people who have always been the audience.

Journalists have an important role to play. If you ask most newsroom editors and producers to work with the public, they will roll their eyes, saying it takes too much time, that the information is too unreliable or that they simply do not have the resources. The reality, though, is that journalists can expand their reach—and their bottom-line profits—by working with the people who have always been the audience.

“Before you share something on your own, think about whether you know it to be true.”

Journalists have used the Society of Professional Journalists’ code of ethics as a way to separate professionals from the public. That has worked so well that even when amateurs do the work of journalism, they refuse to think of it that way. Journalists need to make a shift: We can use guidelines such as the code of ethics as guardrails for the public, to help them do a better job of collecting and disseminating information.

It makes business sense by leveraging newsroom resources to cover more communities and provide more perspectives. This will ultimately bring more people back to trusting and paying for local news. We’re all in this together now.

To support local news, one can start out by supporting the journalists who are still doing the work of telling stories. A half-million Pittsburghers who were paying for local news just five years ago—typically through a newspaper subscription—no longer are. If you still have a newspaper in your community, subscribe to it. If an online news outlet provides information for free, click on the stories, share them on social media, and take a moment to acknowledge the local businesses that advertise on those sites.

We all have a responsibility for information too. Before you share something on your own, think about whether you know it to be true. If it’s just a rumor, don’t tell anyone else, at least until you can check it out. If it’s your opinion, just let people know that’s how you feel without claiming it as the truth.

Local news has changed so much over the past 15 years that we’re still trying to understand what it all means. In the past, professional journalists asked hard questions, showed up at community events, and told the stories of our communities—for better and worse. Now, we all share this responsibility. We can and do contribute to local knowledge, whether we realize it or not.

To listen to the audio version read by author Andrew Conte, download the Next Big Idea App today: