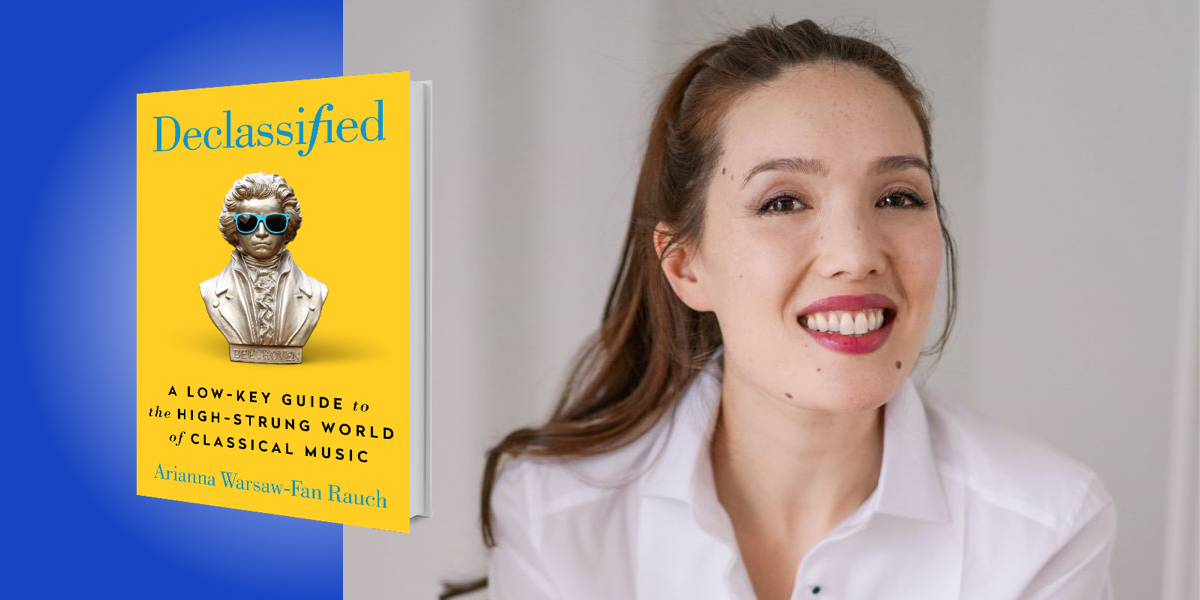

Arianna Warsaw-Fan Rauch was a concert violinist, having performed in top venues such as Carnegie Hall, Boston Symphony Hall, and the Ravinia. She has toured with such legendary artists as jazz trumpeter Chris Botti and Sir James Galway.

Below, Arianna shares 5 key insights from her new book, Declassified: A Low-Key Guide to the High-Strung World of Classical Music. Listen to the audio version—read by Arianna herself—in the Next Big Idea App.

1. Classical music isn’t a monolith—or even a real genre.

A year ago, my kid wouldn’t eat anything green. It didn’t matter whether it was an avocado, a slice of kiwi, or the last of the pistachio macarons that Dadda brought home for Valentine’s Day. If it was tinted or flecked with anything from celadon to emerald, he fed it to the trash can monster before anyone could get it within smelling distance of his face.

To him, the logic was clear: he’d tried a green food once before and hadn’t liked it—so it stood to reason that he’d find all green foods equally objectionable.

Most people approach classical music in a similar way. They’ve heard snippets of it in movies and commercials and elevators—snippets that are chosen to support whatever stereotype said movie, commercial, or elevator is trying to promote—and they think they know how they feel about the entire body of work. But just as kale tastes nothing like Granny Smith apples, which taste nothing like pistachio macarons, Mozart sounds nothing like Shostakovich, which sounds nothing like Bach. The same thing can be said for pop music—you can like Beyoncé without liking Justin Bieber—but the differences are even more pronounced when it comes to classical music.

First of all, Classical Music isn’t a real genre. It’s a collection of hundreds of years’ worth of music written in all kinds of styles and in all kinds of compositional mediums. It encompasses seven distinct compositional periods and countless, widely varied artistic movements. It also offers works for all kinds of ensembles and instrumental configurations. You have things like operas and works for solo piano and string quartets; there’s a much wider range in timbre than in most other genres.

Anyone who says I love classical music or I hate classical music is lying.

2. Classical music itself is not snobby.

Whenever a TV or film director wants to suggest refinement or stuffiness, a piece of classical music will inevitably play in the background of whatever gilded room or formal garden their displaced protagonist has just walked into. If the movie was from the 90s, that piece is generally either Eine Kleine Nachtmusik or Vivaldi’s Spring. But the fact that there are snobs who listen to classical music does not mean that classical music is for snobs.

“Mozart’s music was a reflection of who he was—not of who his various employers were.”

This association between classical music and the moneyed elite is annoying and harmful to the industry, but there is a historical basis for it. Composers like Bach and Mozart had to survive, so they sought employment from wealthy members of the nobility. They—along with many other composers—did not enjoy this system of patronage. Mozart railed against his employer (the Prince-Archbishop Hieronymus Colloredo) in his letters, and Bach was once imprisoned by his patron (Duke Wilhelm Ernst of Saxe-Weimar) for trying to resign.

Furthermore, Mozart’s music was a reflection of who he was—not of who his various employers were—and no one who’s ever read one of Mozart’s songs or poems about poop (or his various body parts) could claim that he was a snob.

Plenty of pieces in the classical repertoire were written to champion the downtrodden or rebel against injustices. Take Shostakovich. His music vividly depicts the horrors of Stalin’s and Hitler’s regimes so powerfully that it was often banned.

Works of classical music encapsulate—at times, with almost unbearable eloquence and sublimity—our shared human experiences. You don’t need money, a musical education, or any education, to appreciate it.

3. Training, not talent.

There’s a line about talent that I’ve heard attributed to David Soyer, who was a cellist, Juilliard teacher, and the notoriously blunt author of many of my favorite classical music quotes. Supposedly, after listening to a prospective student play an entire concerto, he looked the kid in the eye and said, “Either you didn’t practice or you have no talent.” This kick in the nuts highlights an important truth: a talented person who hasn’t put in the time will sound like a person who isn’t talented.

A certain amount of talent is probably necessary to reach any level of proficiency on an instrument. Sometimes talent is staggering, like Mozart who composed whole pieces in his head and then copied them out in one sitting. But so much physical conditioning and muscle control is needed to execute classical compositions at the highest level that without an insane amount of training, talent is moot.

“A talented person who hasn’t put in the time will sound like a person who isn’t talented.”

Here’s what I mean: Ten years ago, I was playing Paganini caprices in international competitions. My hands hurt like hell afterwards but they recovered relatively quickly. If I tried to play a Paganini caprice now, un-practiced, I would end up in the hospital—not just from imploding with self-directed anger. My level of talent, though is the same as it has always been. The difference is physical fitness.

4. Packaging matters.

This industry is frequently packaged and presented in an off-putting way that is wholly unrelated to the actual sounds contained in this repertoire. But Hollywood isn’t the only source fueling the stereotypes of elitism and boredom so often associated with the classical industry.

A lot of people only listen to classical music as background music—at weddings, in shops, or on hold lines. Not only does this leave them with a skewed view of the repertoire (since the pieces generally selected for these purposes are intentionally less than gripping), it also means that they’re not listening in a way that optimizes enjoyment. Classical music doesn’t have those bite-sized hooks that allow you to internalize a song’s main components in just a few listens. Nor does it (usually) have a beat that cuts through the ambient noise. In order to appreciate all of what it offers, you’ll want to give it a bit more focus.

I’ve also often found the traditional visual monotony of the Big Concert Hall Experience to be a mood killer. The sight of an orchestra dressed all in black does little to capture the vibrancy, passion, or playfulness of my favorite compositions. I don’t have the same problem in smaller halls, where I can see performers’ facial expressions and movements clearly—but for me, the boring visuals of the average, large-venue, instrumental concert make the music sound less interesting than it really is. I actually close my eyes at these concerts when I want to get the most from them; I find that this leaves me more open to the music’s offerings.

The nature of many classical music concerts is to make listeners passive rather than participatory. I became particularly aware of this during my time as a featured guest on trumpeter Chris Botti’s tour. Chris is an amazing artist with a huge following. He has this great show that combines jazz, rock, and a bit of classical. I loved how the show lighting took its cues from the music; and the audiences, instead of sitting stiffly in their seats, clapped and cheered and sang. Some of this is difficult with classical music—because Chris’s show was amplified, and one of the great things about classical music is that it isn’t—but there are things that are being done to give listeners more freedom to interact.

5. Classical music is more important now than ever.

Art reminds us of our ability to create beauty despite life’s chaos and strife; it pushes us to look beyond our basic needs and instincts, many of which cause (through the fear they engender) the conflicts of modern society. It also offers a ground for connectivity—a kind of meeting place—that is set apart from these conflicts.

“Music—and particularly this music—speaks to the most powerful feelings; to our most empathetic centers.”

When I think about the way forward for society, it’s hard to foresee any resolution to many of the issues that divide us. While it’s important to discuss these issues, I often wonder whether we might sooner reach mutual understanding if we were to spend time with those who disagree with us partaking in activities or discussions that have nothing to do with those issues. Music—and particularly this music—speaks to the most powerful feelings; to our most empathetic centers.

These days, the classical genre is often seen as a collection of anthems for (white) privilege, exemption, and entitlement. It’s time to use these pieces as anthems of unification and tear down the walls of elitism that have kept the genre isolated and misunderstood. This music deserves it. We all deserve it. Nothing—not respect, not the protection of the law, not education, not music—should be reserved for one small group that sets itself above the rest.

If we all agree to populate this stimulating musical space and allow everyone within this same space the right to voice opinions, then we would feel closer to our fellow humans.

Let’s end by talking about football—or soccer, as I used to call it before I moved to Germany. As far as groups go, All The World’s Football Fans is reasonably diverse in terms of political beliefs, income, education levels, and race. And football fans don’t agree on much (least of all football) but they all get goosebumps when they hear the UEFA’s Champion’s League anthem. The anthem was written by Handel. It’s called Zadok the Priest, and it’s awesome.

UEFA could have chosen from any number of songs in any number of styles or commissioned their own anthem from any number of artists. But as they were making their choice in 1992, it was a coronation anthem written by Handel over two centuries earlier that spoke to them—that still speaks to millions of football fans every year.

To listen to the audio version read by author Arianna Warsaw-Fan Rauch, download the Next Big Idea App today: