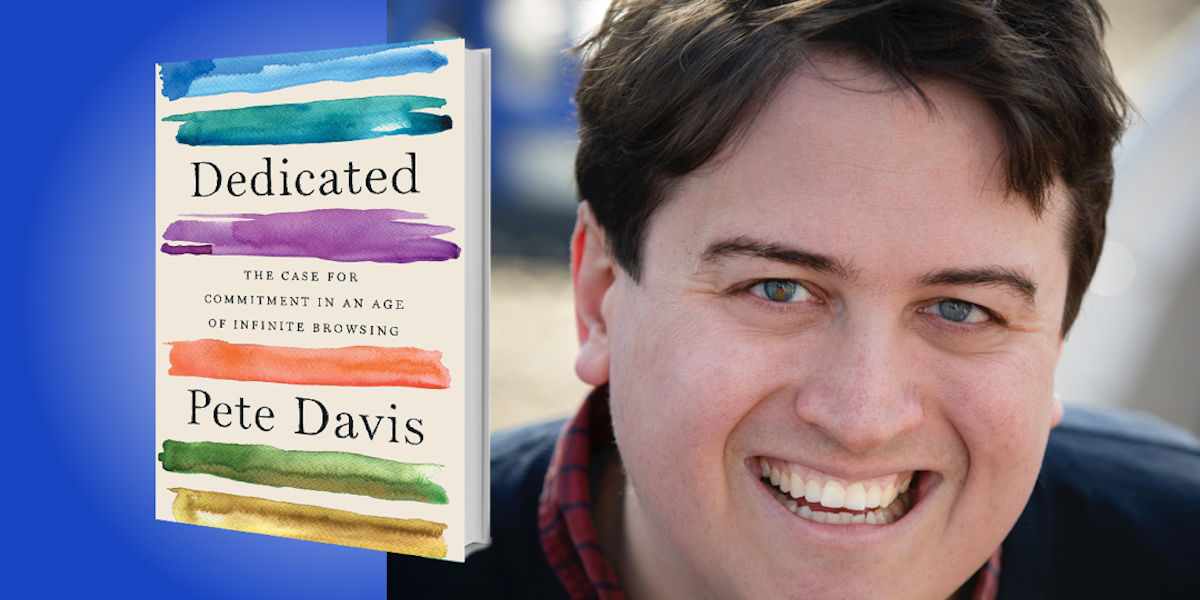

Pete Davis is a writer, civic advocate, and co-founder of the Democracy Policy Network. His new book, Dedicated, is based on the 2018 graduation speech he gave at Harvard Law School, a speech that has been viewed more than 30 million times.

Below, Pete shares 5 key insights from his new book, Dedicated: The Case for Commitment in an Age of Infinite Browsing (available now from Amazon). Listen to the audio version—read by Pete himself—in the Next Big Idea App.

1. Don’t get stuck in Infinite Browsing Mode.

I’m sure you’ve had this experience: It’s late at night and you start browsing Netflix, looking for something to watch. You scroll through different titles, you even read a few reviews—but you just can’t commit to watching any given movie. Suddenly it’s been thirty minutes and you’re still stuck in Infinite Browsing Mode, so you just give up. You’re too tired to watch anything now, so you cut your losses and fall asleep.

I’ve come to believe that this is the defining characteristic of my generation: keeping our options open. The Polish philosopher Zygmunt Bauman has a great phrase for this: he calls it liquid modernity. We never want to commit to any one identity or place or community, so we remain—like liquid—in a state that can adapt to fit any future shape. Liquid modernity is like Infinite Browsing Mode, but for everything in our lives.

We want the flexibility, the authenticity, and the novelty of browsing, but we want more than the paralysis, the isolation, or the shallowness that comes with it. This is why, even though we’re often stuck on the menu screen of life, we know, deep down, that we want to pick a darn movie and see it all the way through … before we fall asleep.

“This is the defining characteristic of my generation: keeping our options open.”

2. A Counterculture of Commitment awaits you.

As I have grown older, I have become more and more inspired by the people who have clicked out of Infinite Browsing Mode. It’s Fred Rogers recording 895 episodes of Mister Rogers’ Neighborhood because he was dedicated to advancing a more humane model of children’s television. It’s the Catholic Worker founder Dorothy Day sitting with the same outcast folks night after night. It’s Martin Luther King Jr.—and not just the Martin Luther King Jr. who confronted the fire hoses in 1963, but also the Martin Luther King Jr. who hosted his thousandth tedious planning meeting in 1967.

These folks aren’t just a random assortment of people. I’ve come to think about them as part of a shared counterculture—a Counterculture of Commitment. All of them took the same radical act of making commitments to particular things—to particular places and communities, to particular causes and crafts, to particular institutions and people.

The kinds of people I’m talking about here are rebels—they live their lives in defiance of the dominant culture of novelty. They build relationships with particular things—and they show their love for those relationships by working at them for a long time. And this Counterculture is looking for new members. There is no better time than now to rebel from liquid modernity by doing what solid people do: dedicating yourself to something bigger than yourself.

3. Ditch Hollywood dragon-slaying for long-haul heroism.

When Hollywood tells tales of courage, they usually take the form of “slaying the dragon”—there’s a bad guy and a big moment when a brave knight makes a definitive decision to risk everything to win some victory for the people. It’s the man standing in front of the tank, or the troops storming up the hill, or the candidate giving the perfect speech at the perfect time.

“That’s what life tends to give us: not big, brave moments, but a stream of little, ordinary ones out of which we must make our own meaning.”

But what I’ve learned from dedicated people is that Hollywood heroism isn’t the only valor around. It’s not even the most important type of heroism for us to model, because most of us don’t have to face many dramatic, decisive moments in our lives—at least not ones that spring up out of nowhere. Most of us just confront daily life, normal morning after normal morning, where we can decide to start working on something or keep working at something—or not. That’s what life tends to give us: not big, brave moments, but a stream of little, ordinary ones out of which we must make our own meaning.

The heroes of the Counterculture of Commitment, long-haul heroes—through day-in, day-out, year-in, year-out work—become the dramatic events themselves. The dragons that stand in their way are the everyday boredom and distraction and uncertainty that threaten sustained commitment. And their big moments look a lot less like sword-waving and a lot more like gardening.

4. We need to overcome the fears of regret, association, and missing out.

What stops us from diving into commitments? Three fears.

First, we have a fear of regret: We worry that if we commit to something, we will later regret having not committed to something else.

Second, we have a fear of association: We think that if we commit to something, it will threaten our identity, our reputation, and our sense of control.

Third, we have a fear of missing out: We fear that if we commit to something, the responsibilities that come with the commitment will prevent us from being everything, everywhere, with everyone.

“We do something holy in the extraordinary moments when we set out on long hauls.”

But when you talk with folks who are deep into their own long hauls, you’ll learn that these fears start to fade as soon as you dive into something.

When you’re dedicated, you stop fearing missing out on the latest novelty, because you get to experience the sweetest novelties of all—the novelty of mastering a craft, or celebrating an anniversary, or watching your project take off. You stop fearing the chaos of association, because the discomfort and insecurity of community-building eventually transforms into the deep comfort and security of having old friends. And, finally, the fear of regret fades because your commitment starts becoming part of you. You stop feeling like you are always actively choosing to continue being committed to something outside of you. Instead, the commitment starts feeling inside of you—your commitment becomes part of who you are.

5. On the other side of our fears of commitment is peace and joy.

The grim fact looms: Our time is limited. For many of us, this is behind our infinite browsing. For some, our fear drives us to endless novelty as we try to play every game at the carnival before closing time. For others, our fear paralyzes, heightening our indecision. The poet Mary Oliver once asked: “Tell me, what is it you plan to do with your one wild and precious life?” I think she meant it as an encouragement, but some of us might find the question haunting: What if I plan wrong?

But long-haul heroes will tell you that the more we dedicate ourselves, the more these fears fade. Commitment is about choosing to pursue—in the face of our limited length—boundless depth, for the more time we add to something, the more beautiful it becomes. The two meanings of the word “dedicate” are revealing. First, it means to make something holy (like “dedicate a memorial”). But it also means to stick at something for a long time (like “she was dedicated to the project”). I don’t think this is a coincidence: We do something holy in the extraordinary moments when we set out on long hauls, and we do something holy in those countless ordinary moments when we sustain them.

To listen to the audio version read by Pete Davis, download the Next Big Idea App today: