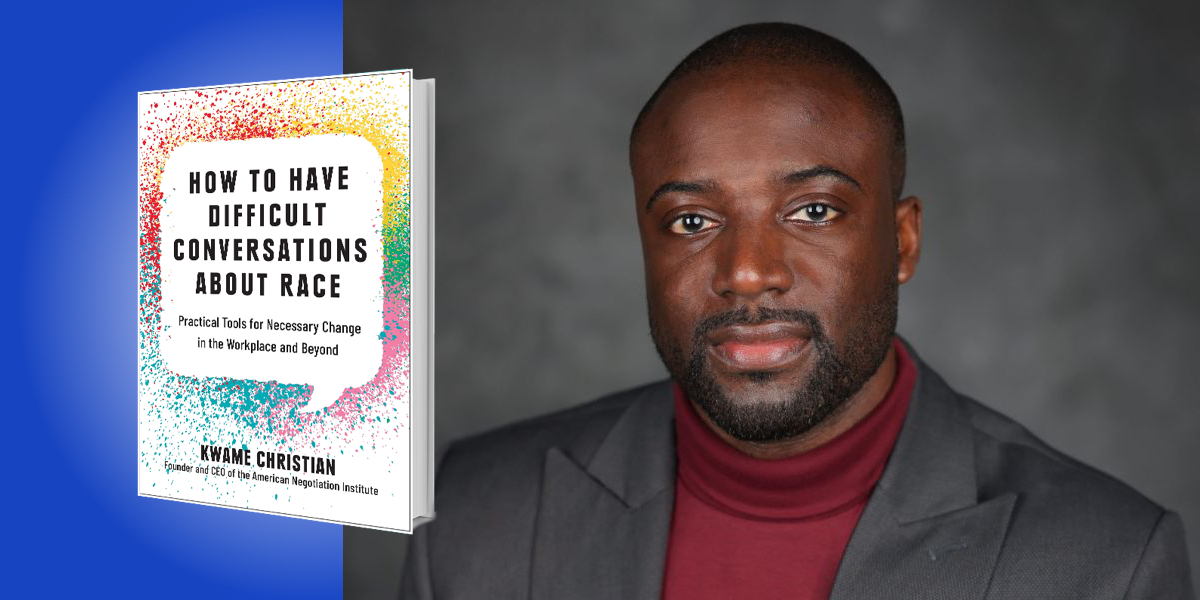

Kwame Christian is the founder and CEO of the American Negotiation Institute and the host of the Negotiate Anything podcast. He is also a business lawyer at the law firm of Carlile Patchen & Murphy LLP, a contributor at Forbes, and professor of negotiation for The Ohio State University’s Moritz College of Law and as a professor of communication and negotiation at the MBA program at Otterbein University.

Below, Kwame shares 5 key insights from his new book, How to Have Difficult Conversations About Race: Practical Tools for Necessary Change in the Workplace and Beyond. Listen to the audio version—read by Kwame himself—in the Next Big Idea App.

1. We talk about race because we care.

We have difficult conversations about race because we care, but what is it that we care about? We care about our colleagues and we care about our relationships with them. We care about fairness and we care about progress. When you care about something, you talk about it.

There’s nothing in the world that people care about that they don’t talk about. One of the easiest ways to show your colleagues that you care is by talking about things that matter.

2. Understanding the psychology behind difficult conversations is a good first step.

Difficult conversations about race are especially challenging because they trigger heightened emotional responses and they involve psychological considerations like bias. Conversations about race trigger heightened levels of emotionality for two main reasons. It comes down to identity and morality. Identity, of course, involves asking oneself the question, who am I? But it also begs the following questions: What does a person like me do in these types of situations? What does a person like me say? What does a person like me believe?

Morality, on the other hand, involves questions that define what it means to be a good or bad person. When those two things seem to be challenged or threatened in any kind of interaction, it is going to heighten the level of emotionality. Understanding that will help us to create strategies to circumvent that.

It’s also important to consider bias. Bias is a subconscious preference towards or prejudice against something. It’s usually either reflexively good or reflexively bad. Not only is it crucial to identify the different biases that could be at play in these interactions but it’s also important to feel empowered about the reality of biases.

Many times, when we talk about bias in the workplace, we only look at it from a negative and disempowering perspective. We need to approach bias as a strategic consideration. What biases could be working against me? And now, strategically, how can I work against those types of things? What are some of those positive biases that I can mobilize in order to overcome some of those negative biases?

“There are effective ways to strategically use affinity bias in an interaction in order to overcome potential biases that may exist.”

There is a bias called the affinity bias, which put simply is “I like you because you are like me.” When we look at somebody else and we see a bit of ourselves in them, we tend to like them more. That is a positive bias that we could have toward somebody. There are effective ways to strategically use affinity bias in an interaction in order to overcome potential biases that may exist.

Several studies that have shown consistent bias in healthcare against Black, Latinx, and other dark-skinned patients. Knowing this back when my wife Whitney was pregnant, I would accompany her for maternity wellness checks, during which I would always find a way to casually mention that Whitney was a doctor. The doctors’ or nurses’ eyes would always light up and they would ask where she practiced or if she knew an acquaintance in the field. As soon as they knew that they were talking to a fellow medical professional, their whole demeanor changed, along with their treatment of Whitney. We didn’t know in advance whether or not she was going to be treated unfairly, but we minimized the likelihood by clearly demonstrating a similarity to her caregivers.

Bias doesn’t only affect our decision-making and how we treat other people. It also impacts how we perceive objective reality. In one study, researchers performed an experiment where they had participants taste wine while in an MRI scanner to record their brain activity. Researchers in the study showed the participants the price of a wine and then allowed them to sample that wine and then rate it based on how much they enjoyed it. The researchers then repeated the steps with a differently priced wine. What the participants didn’t know was that they were given the same wine both times. The only difference between the wines was how much the participants were told they cost. Despite this fact, the subjects reported that the more expensive wine tasted better than the cheaper one. The participant’s brain activity was also greater when they tasted the wine with the higher price point. This shows that they genuinely perceived a difference in taste because of their beliefs about the wine.

When you take that study and replace wine with people though, it becomes really dark. This becomes troubling, because we realize that people, even while walking and talking with each other, may be living in completely different realities. Biases can completely color life experiences and how we perceive the world. As much as we would love to resolve conflicts using facts and data, we have to recognize that bias is going to contort reality in a way that could potentially be problematic.

3. We can reach our collective goals through perspective expansion and keep the conversation on track through conversational leadership.

How many times do we go into these impactful conversations with a strategy? Put simply, a strategy is a plan that helps you win. When talking about winning in the context of these difficult conversations, the strategy should be to reach your goals for that conversation. Winning should mean moving toward an ultimate goal. If through these conversations we are able to deepen our mutual understanding and knowing more than when we began, then we are winning. The only way we can do this is by being goal-oriented. We need to make sure that the strategies that we put together are taking us closer to our goals.

As mentioned before, these conversations can be very emotional. If you are very emotional, these tough conversations may tempt you to use cathartic communication—where you are venting at your opponent. This is not persuasive. It does not get you closer to your goal unless your goal is simply to hurt people.

“Biases can create blind spots, so there might be a part of the elephant you aren’t seeing.”

Remember also that this is the context of the employment setting, so one way to avoid cathartic communication is called perspective expansion. There’s a folktale called “The Blind Men and the Elephant.” Six blind men are asked to describe an elephant based only on touch. Not surprisingly, based on where they touch the elephant, each gives a very different description. One man feels the tusk and describes the elephant as a spear. One man feels the leg and says an elephant is like a big strong column. Another man touches the tail and says that an elephant is like a rope. The men began arguing about who is right and who is wrong. The answer is that they are all right and wrong at the same time, based on which part of the elephant they’re experiencing. Our biases are the result of our lived experiences and the way we grew up. Who taught us growing up? What type of media do we consume? We’re all experiencing different parts of the elephant.

The question to ask yourself then is which part of the elephant are you seeing? Biases can create blind spots, so there might be a part of the elephant you aren’t seeing. Instead of attacking a person directly, take the time to empathize, listen, and understand what they are seeing. Once the conversation is led by listening, it makes it more likely for the other person to listen to you. Listening and vulnerability are reciprocal in nature. You have to give it first in order to receive it.

Conversational leadership is another strategy. This method means not just thinking of oneself so much as trying to have an effective conversation with someone else. Through the conversation, you may be coaching the other person as to how to effectively have a conversation, while simultaneously sharing my side of the elephant. It is an approach that doesn’t directly attack what people are believing or what they’re feeling. Remember, just like the wine, it’s not just that they have been deceived. It is that, based on their perceptions and biases, they genuinely believe what they’re saying to be true. It’s not an issue of right or wrong in this case. Conversational leadership is a patient, respectful, humble approach of expansion that helps us to overcome biases.

4. Approach conflict with a compassionate and curious framework.

Compassionate curiosity framework is a unique approach to handling difficult conversations. The goal is to help us to understand what to say and when to say it with maximum impact. It is a three-step framework that can be used not only in the external conversation with your conversation partner, but also internally, as a tool of introspection, emotion management, and bias reduction. The first step is to acknowledge and validate emotions. The second is to get curious with compassion. The third step is joint problem-solving, so you will know what to say and when to say it with maximum impact.

For example, let’s imagine a difficult conversation where one person becomes emotional. Step one is to acknowledge and validate the emotions. Use phrases such as “it sounds like,” “it seems like,” or “I can tell that.” That places an emotional label on the person, and gives them the opportunity to decompress and vent, calming down through the process. The next step is getting curious with compassion. We do that by asking open-ended questions with a compassionate tone to gather information and empathize with the other side. Thirdly, we’re going to work with them to solve the problem. We want to answer these questions: what does our relationship look like going forward? How do we work together collaboratively to solve the problem at hand? It should feel like a brainstorming session where you’re working through those challenges together.

“Joint problem-solving directed internally is reconciling the differences between your heart and your mind.”

This process also works internally. First, you can acknowledge and validate your own emotions. Label those emotions to yourself. Then you’re going to get curious with self-directed compassion. You might hypothesize that you have a bias. If you are confronted with that reality in your introspective process, you might be too hard on yourself, so also approach these conversations with self-directed compassion.

Lastly, joint problem-solving directed internally is reconciling the differences between your heart and your mind. What will satisfy you emotionally? What is the emotional challenge you’re trying to overcome? At the same time, consider what is it that you need to do. What is the decision that you need to make? What do you need to say in this difficult conversation to solve the problem?

5. Anyone can be an advocate.

If a tree falls in the woods and nobody hears it, did it really make a sound? I always thought this was a really silly question—my response was “Who cares?” But if we replace a few words, we get a very different question. If an advocate isn’t able to create positive change, are they really an advocate? If you call yourself an advocate, but your words and actions don’t lead to meaningful change, then are you really an advocate?

When we think about the difference between an advocate and an ally, it can be confusing. To advocate is to speak on behalf of or support. In my view, the term advocate is more appropriate because it focuses on taking action, using persuasion and influence regardless of your racial identity. Whether or not you deserve the moniker depends on whether or not you’re actually able to create positive change.

A crucial part of being able to create change is how active of a role you’re taking in persuading the people around you. If you want to maximize your impact, start with this simple truth. Racial inequity is a problem of bad policy, not bad people. You’ll get a greater return on investment if you focus on the policies that shape an organization rather than the personal beliefs of the individuals within it.

To listen to the audio version read by author Kwame Christian, download the Next Big Idea App today: