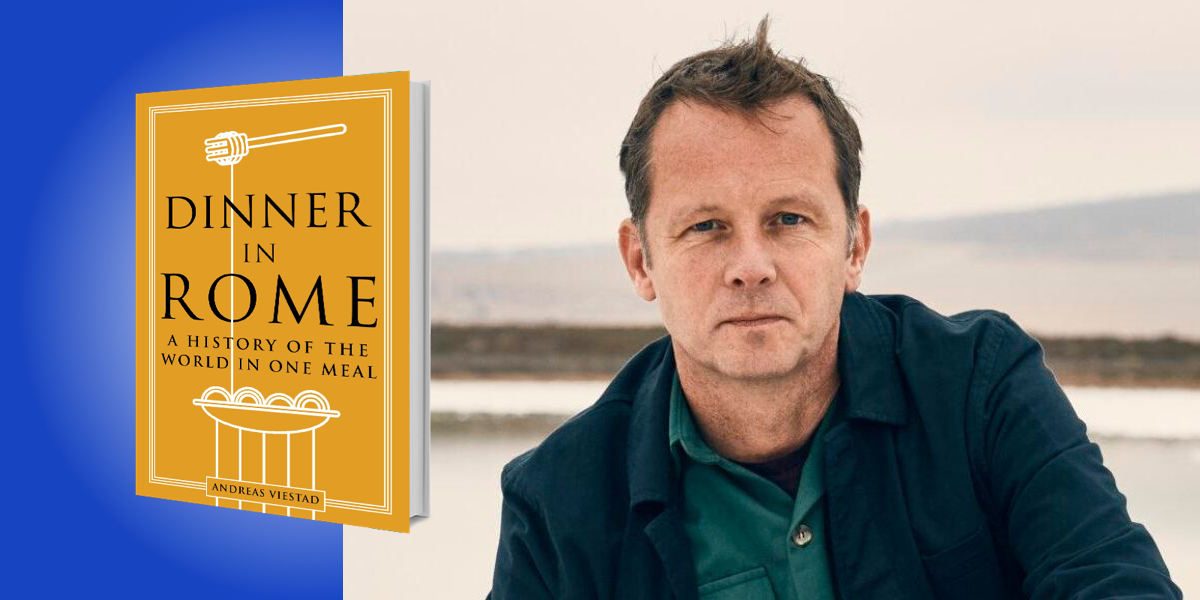

Andreas Viestad is a food writer, TV chef, restaurateur, and food activist. He is the longtime host of New Scandinavian Cooking airing on PBS in the United States and in over fifty countries, a former columnist for the Washington Post, and a founder of Geitmyra Culinary Center for Children in Norway. He lives between Oslo and Cape Town.

Below, Andreas shares 5 key insights from his new book, Dinner in Rome: A History of the World in One Meal. Listen to the audio version—read by Andreas himself—in the Next Big Idea App.

1. There is more history in a bowl of pasta than in the Colosseum, or any other historical monument.

I am married to an archaeologist, and when we are in Rome, one of her professional superpowers is evident. She can look at a piece of marble or a broken pillar, imagine the building that once stood there, and help tell the story of the civilization that built it. We can walk around like this for hours, getting lost in the past. And then, after a long day, we sit down for a meal. Finally, we can relax—enjoy great food and wine—free from the never-ending history lesson that is Rome.

But gradually I have started thinking that I can use the same method that archaeologists use when studying buildings and artifacts to understand the food we eat. To annoy my wife, I called it “culinary archeology”—but the term has stuck.

Imagine a bowl of pasta. It can tell a story that is almost limitless. Pasta is an essential part of Italian culture. The story of how pasta spread from Naples to the rest of Italy in the 19th century is the story of how Italians started to realize that they might all belong to the same nation. The wheat that the pasta is made of is an essential story of the Roman Empire. The empire wasn’t built by generals and emperors. To a large extent, it was a function of the unique food system, based on wheat, where the Romans conquered new lands, planted them with wheat—if there was no wheat there already—and collected the wheat in taxes, which they in turn used to pay as salaries for their ever-expanding army, and sent back to Rome to ensure that the city’s poor did not riot. The wheat in the pasta can also tell an even bigger story of how humans went from being hunters-gatherers to becoming farmers, and then eventually city dwellers with written languages—all because we started growing wheat, and we became hooked on it.

2. We all descend from the first cooks.

There is a story of humanity that we have all heard: humans were the smartest animals, and our smartness is what led us to tame fire and then to master all the technologies derived from fire. Steel, steam engines, iPhones—you name it. But how did we become so smart?

The primatologist Richard Wrangham claims that it was not humans but early hominins—an ape, roughly speaking—that first started using fire. The use of fire made it possible for us to utilize much more of the energy in the food we ate, and we did not have to spend all day chewing. Cooking with fire gave us the super-sized brains we have and everything that came after.

In Dinner in Rome, I take a detour from Rome and visit the Wonderwerk cave in South Africa, one of the places where this transformation probably happened, and where the oldest traces of controlled use of fire, dating back 1.2 million years, are found.

“Cooking with fire gave us the super-sized brains we have and everything that came after.”

So fire, and cooking, are what made us human. And that means that we are all descendants of the first cooks.

3. The mafia got its start with lemons.

In the 1860s, Italy had just been unified. In Sicily, that meant that the former rulers and their power structure had collapsed. At the same time the island had just introduced a new commodity to the world market: the lemon.

There was a craze for lemons, first on mainland Italy, then in a lot of other European countries, and then in the United States and the rest of the world. Growing and trading lemons was by far the most lucrative agricultural activity. The lemon groves of Sicily were even more profitable than the most prestigious vineyards of Burgundy and Bordeaux.

As early as the 1870s, there were reports of a new organization that controlled the production and trade of lemons. They didn’t own the orchards or the transport. They stepped in for the old Dons, ran extortion schemes, and demanded protection money to ensure there were no “accidents.” As the historian John Dickie has written, the organization soon spread to the United States, where they expanded their business. In fact, the first shipments of drugs were smuggled in lemon crates.

“The lemon groves of Sicily were even more profitable than the most prestigious vineyards of Burgundy and Bordeaux.”

Think about that the next time you have a glass of lemonade.

4. Taste is important.

When food is mentioned in the telling of history, it tends to be seen only for its calories. That makes sense. When food is lacking, it can lead to famine and disaster. But that is not all food is capable of—not by a long shot. History shows us that we humans care a lot about taste. Once we have enough to fill our bellies, we are willing to go to extremes to ensure that the food tastes good. The most vivid example of this is our relationship with spices.

Two thousand years ago, the Romans were obsessed with spices. One of the oldest cookbooks in the world, De Re Coquina, ascribed to the Roman nobleman Apicius, mentions pepper 468 times! There is pepper in nearly everything, from Roman staples like sausages, shellfish sauce, salads, brain pudding and meats, to wine and desserts. You might have heard that the ancients used pepper and other spices for medicinal purposes, or that it was supposed to mask spoilt meat. That is simply not true. They liked pepper for the same reasons we grind it over our steaks or our pieces of chicken: because it makes the food more interesting.

The hunger for spices was so great that it changed the world. The search for a route to the spice-producing areas in and around India led to the Age of Exploration in the 15th century. When Columbus ventured west, he was searching for the spices of India. When he did not find pepper, he was rather disappointed. And he named more or less everything he found pepper. Allspice? “Jamaica pepper.” Red hot chilies of the Americas? “Chile peppers.”

5. The universe has a center.

If you have been to Rome, you are lucky. If you haven’t, you are even more lucky, because then you have a wonderful, life-changing experience ahead of you.

In the middle of Campo de’ Fiori, where my meal in Dinner in Rome takes place, there is a statue of the 16th century scientist Giordano Bruno. Bruno was one of proponents of the Copernican model. This was the idea that the stars were not merely things drawn on the firmament to give us something to look at; they were suns, just like our own. He claimed that space was immense and the sun did not circle around the Earth but the other way around. The problem with this theory in the 16th century was the implication. It meant that God was not all powerful, the stories in the Bible were not facts to be taken literally, and the words of the Papal church were not infallible.

“Today, [Bruno] is considered a hero, and most of his claims are widely accepted: they are now a part of our collective worldview.”

Bruno was prosecuted as a heretic and burned at the stake in this square on February 17th, 1600. History has been harsh on Bruno’s judges, and the executioners who tied him to the stake with his head down and legs up, then set fire to him and let him burn. Today, he is considered a hero, and most of his claims are widely accepted: they are now a part of our collective worldview.

I have spent a lot of time in Campo de’ Fiori, looking at the statue of Bruno, and I have been inspired by his challenge to look at the world from a new perspective. In my case I want to look at the way we explore the role of food in history.

But Bruno was wrong about one thing. If you spend an evening at the restaurant La Carbonara, and—after bread and oil, an artichoke as antipasti, pasta carbonara with just the right amount of pepper, some grilled lamb, a lemon sorbet, and one too many glasses of red one—you step into the mild night of the Eternal City, filled with history, surrounded by history, then you know that the universe has a center, and that it is here, at Rome’s Campo de’ Fiori.

To listen to the audio version read by author Andreas Viestad, download the Next Big Idea App today: