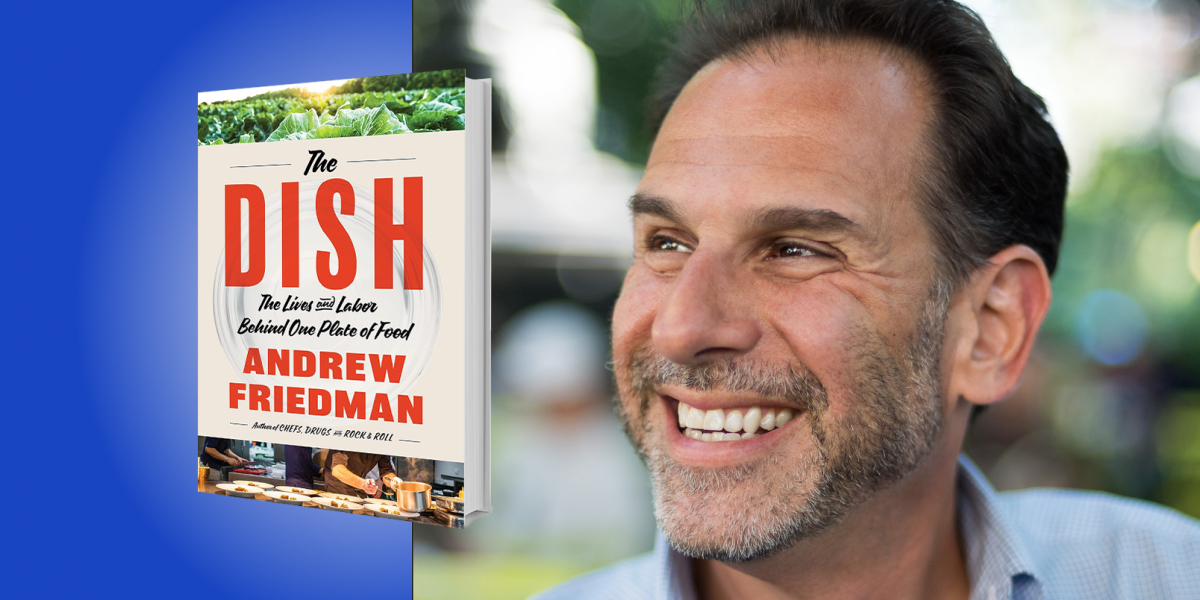

Andrew Friedman is an author, editor, podcast producer, and host of the independent podcast Andrew Talks to Chefs, currently in its sixth year. He has co-authored over 25 cookbooks. Additionally, he is an adjunct professor within the School of Graduate and Professional Studies at the Culinary Institute of America.

Below, Andrew shares five key insights from his new book, The Dish: The Lives and Labor Behind One Plate of Food. Listen to the audio version—read by Andrew himself—in the Next Big Idea App.

1. Despite appearances to the contrary, most restaurant meals are priced lower than they should be.

There’s a well-known, decades-old anecdote about the late French chef Paul Bocuse. The story is one that people in the restaurant industry still share with one another, and with their guests, even today. And it continues to provoke laughter and knowing nods:

Once, while Bocuse was visiting with a table of diners in his restaurant, a member of the party asked him, “Who’s cooking our dinner while you’re out here?” His response: “The same people who cook it when I’m back there,” meaning in the kitchen. The story has abided for decades because it punctures a fantasy about professional kitchens, namely that the chef does all of the cooking.

In reality, a chef, if they cook at all, only does it minimally. Most of their time is consumed managing the overall restaurant organism, coaching members of their team, tasting elements of various dishes as they are prepped by others throughout the day, and then orchestrating, referred to in a restaurant as “expediting,” all of the moving parts during service, meaning when guests are being cooked for and served. Most of the physical work is done by prep cooks, line cooks, and sous chefs—people we diners don’t see unless the kitchen is an open one, visible to the guests.

Beyond the restaurant, food, regardless of where it comes from, takes more people to grow or raise, and then harvest and pack, than you might expect.

“In reality, a chef, if they cook at all, only does it minimally.”

An example is a meat purveyor whose family operation takes a variety of livestock from pasture to restaurant. Even that relatively small business employs stable workers, two slaughterers, a team of butchers, packers, helpers, and delivery truck drivers, and that’s not including the USDA inspector for whom they are legally required to provide, at the farm’s expense, an office with a dedicated landline telephone. Add it all up, across all the component parts of a meal, and the ingredients required to produce them, and we begin to glean a sense of what owner-operators have known for generations: Restaurant food, though it can sometimes seem exorbitant, is usually priced lower than it would need to be for the restaurant and its suppliers to make a significant profit and/or function with comfortable margins.

2. Most restaurant people don’t commit to their chosen industry at the outset of their working lives.

Even though we live in a time when chefs potentially can become celebrities and earn a lucrative living, the culinary trade retains much of its historical reputation, which is that of a dirty, low-paying, and unskilled occupation. Accordingly, young people, as they did back in the 1970s and 1980s, often meander a bit, or even try one or more different fields altogether, before they take the plunge and start working in or training for professional kitchens.

In my book, we meet a former musician, a former aspiring photographer, and a few former wanderers who chose aimlessness over another profession until cooking sparked their imagination. In most cases, a cook-in-waiting requires what I refer to as a portal—a restaurant job that excites and haunts them (in a good way) until, sometimes after a period of years, they realize that cooking is what they want to do. Oftentimes the portal is a random job taken during high school or college to earn tuition or spending money, that ends up unexpectedly activating somebody’s inner cook.

Another factor in delaying one’s commitment to the pro kitchen: familial resistance, which isn’t as strong a headwind as it used to be. Of the characters in the book, only two experienced significant parental pushback to taking the kitchen path, though in one case it was especially harsh. The silver lining? It helped push the chef in question to prove her parents wrong and fuel her success.

3. Sometimes the most seemingly straightforward jobs are the most complex.

Following the key ingredients of a dish through their entire life cycle, from farm or field to plate, we come to meet people who do jobs we’ve probably never considered in much detail.

In some cases, the person whose job is most deceptively complex is the owner-operator themselves. For example, we meet several farmers who operate largely on instinct sharpened by years of experience. We also meet a cook who can tell the doneness of a steak merely by poking its exterior. The vintner whom we meet (because our dish is sauced with a reduction of one of his red wine blends), can discern whether the grapes on his vines are doing well or require supplemental nutrients, simply by observing their color and size.

“We also meet a cook who can tell the doneness of a steak merely by poking its exterior.”

Other roles are more surprising in their complexity. For example, we meet a delivery truck driver for one of the farms for this particular dish. Located in Chicago, that driver has to endure finding parking for his truck at a variety of restaurants throughout the day in order to get the farm’s food to them. This is the stuff of reality competition television shows. He does it with good humor and aplomb, and without the aid of GPS or order fulfillment software, which impressed me no end.

For all of the experts in the book, there’s only one person I met whose job I don’t think I could do myself with proper training, and that’s making food deliveries in a big city. I’m reasonably sure that I would find it crushingly stressful, and that ultimately, I’d fail. Like most other specializations needed to provide one plate of food, delivering is one that suits certain personality types and temperaments, and demands more skill than meets the eye.

4. Restaurants and farms, like people, comprise myriad intersecting systems.

The Dish is told during a restaurant service. We follow one table’s main course, a meat course, from the time a party’s order is put in, to when the dish is presented to them 75 minutes later, after the other savory courses that make up their dinner. As elements of the dish are readied, we break away from the action to meet the restaurant worker handling it, the farmer from whose business it came, or another member of the restaurant’s extended professional web. In the end, we finally return to the action in the restaurant.

During this time, we observe various systems that enable the restaurant to run and the picture that emerges isn’t that different from how we regard the human body. For example, in what might be deemed the restaurant’s pulmonary system, the restaurant can be said to inhale revenue from guests and exhale it in payroll, food purchasing, rent or mortgage payments, and other expenses. Other systems in this construct would be the bar and the dishwashing department. Then there’s the hospitality system, i.e., the servers, which deliver the other systems’ products to the guests, and bring back any waste.

For a sense of the reach of just one system, let’s look at that hospitality system. We might think of it as a hybrid of the nervous and circulatory systems in human beings—more specifically, servers as neurons and food runners as blood cells. What do I mean by that? Well, servers communicate information that triggers other actions. They convey the wishes of each guest to the kitchen, which then produces certain dishes for them. The food runners are the circulatory system because they transport nutrients (in this case, plated food) and remove waste (empty dishes and glasses) from tables. It’s a hybrid system because servers often perform the role of runners, and runners sometimes are drafted by customers into the role of server, as when they ask a runner to add something to their order when a course is delivered to the table.

“During this time, we observe various systems that enable the restaurant to run and the picture that emerges isn’t that different from how we regard the human body.”

We can say the same of the farms: greenhouse managers, pickers, cleaners, packers, drivers, and others work in synchronicity to keep product flowing out, and revenue flowing in. We may think of restaurants and especially farms as more—no pun intended—organic enterprises. We romanticize them and their operations. In reality, their component parts have corollaries in any production-oriented industry.

Like people, restaurants and farms appear as single, unified entities. But inside, where we can’t see, is a mind-boggling collection of interacting systems that make the organism run and, we hope, sustain its life.

5. To the general population of restaurant patrons, the dishwasher is the most undervalued and misunderstood role.

Firstly, restaurant plates, generally speaking, do not accumulate in the dish area until the end of a breakfast, lunch, or dinner service. We’ve all seen old movies where a customer realizes they don’t have their wallet with them and has to wash dishes as barter for the meal at the end of the night. That trope is not based on reality. Restaurants have limited supplies so dirty dishes must be cleaned and sanitized, dried, and returned to the kitchen on a rolling basis. If the dish pit can’t keep up, the line may back up, seated customers’ food will be slow to arrive, tables won’t be vacant when they’re supposed to honor the next round of reservations, and so on.

As for the people who occupy the dishwasher position, overgeneralizing—but only slightly—they tend to break down into two groups: those who are likely to spend their working lives in this role, and those for whom it’s a portal to the kitchen life. Dishwashing is, and has always been, the main point of entry for future cooks and chefs. The job considered the dirtiest and least glamorous turns out to be just as important as the most visible and celebrated positions, which is kind of the point. Everybody matters. Everybody should be appreciated.

To listen to the audio version read by author Andrew Friedman, download the Next Big Idea App today: