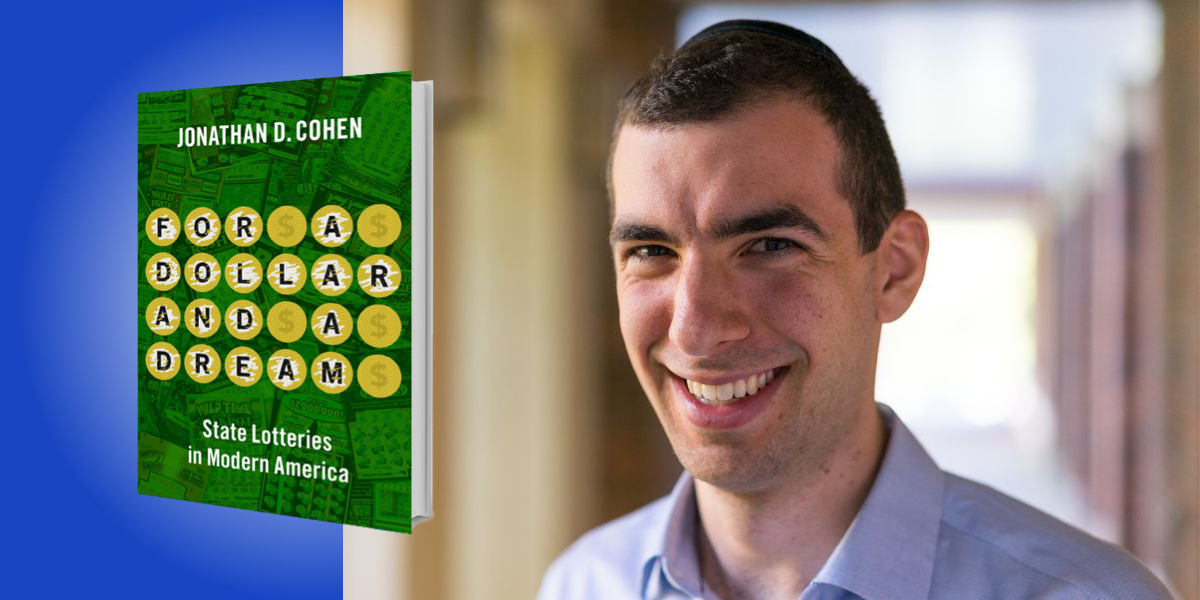

Jonathan D. Cohen is a historian and program director of American Institutions, Society, and the Public Good at the American Academy of Arts and Sciences.

Below, Jonathan shares 5 key insights from his new book, For A Dollar and A Dream: State Lotteries in Modern America. Listen to the audio version—read by Jonathan himself—in the Next Big Idea App.

1. Lotteries are more popular than you think.

Americans spent roughly $98 billion on lottery tickets last year. For reference, that’s more than Americans spent on cigarettes, coffee, or smartphones. It’s also more than they spent on video streaming services, concert tickets, books, and movie tickets combined. Roughly half of American adults play the lottery at least once a year, one in four do so at least once a month, and one in eight plays at least once a week.

Who exactly is spending all that money on lottery tickets? Americans from almost every walk of life play at least occasionally. The top 20 percent of players, though, account for as much as 80 percent of lottery sales. Relative to the overall population, this group is disproportionately black or Latino, male, lacking a high school diploma, and below the twentieth income percentile.

On the surface, this seems to confirm the old adage that a lottery is a “stupid tax” or even a “tax on people who are bad at math.”

2. Many Americans judge the long odds of a jackpot as their best chance at a new life.

Some lottery players wishfully and incorrectly believe they are due for a massive windfall. But it is wrong to attribute the popularity of lotteries to players’ misunderstanding of probability.

Lotteries are popular in large part because the traditional economy does not provide enough opportunity to get ahead. In the late twentieth century, as lotteries spread across the country and became a weekly purchase for millions of households, rates of upward mobility stagnated. High-paying manufacturing jobs disappeared and high-growth industries became increasingly concentrated in certain parts of the country. Many Americans found themselves shut out of the American Dream and the opportunity for financial stability.

“The size of today’s jackpots also reflects the standards of wealth in today’s society.”

Many people turned instead to lotteries. In a 2006 poll, almost 40 percent of households with incomes under $25,000 believed their best means of accumulating a large fortune was through the lottery. A 2010 poll asked respondents to name the most likely way for them to get rich; almost as many people chose the lottery as said they would get rich by starting their own business or securing a high-paying job. During periods of economic decline, casino and horserace gambling revenues typically drop. Meanwhile, lottery sales increase as incomes fall, unemployment grows, and poverty rates rise.

The size of today’s jackpots also reflects the standards of wealth in today’s society. As the rich got richer, the amount of money needed to achieve “the good life” grew. Success no longer meant a home in the suburbs with a white picket fence, but a mansion with a few sports cars in the driveway. This was the kind of wealth that seemingly only a lottery jackpot could provide.

“We sell hope in this depressed economy,” an Ohio Lottery official once explained. “We don’t sell lottery tickets. We sell dreams.”

3. Many gamblers aren’t only playing to win, they are playing for the chance to dream.

For anyone who doesn’t play the lottery, the appeal may seem perplexing. Why would someone spend hundreds or thousands of dollars a year on what amounts to slips of paper with a bunch of worthless numbers or symbols printed on them? Lottery tickets seem like lousy forms of entertainment when compared to a movie ticket.

My conversations with lottery players across the country reveal that when people buy tickets, especially for big jackpot games, they are really purchasing the chance to imagine what they would do if they won. For a few minutes, a few hours, or a few days, that ticket offers permission to fantasize and imagine dreams coming true. The lottery represents a vehicle of escapism for a lot of people. Lotteries can serve as an escape into a world where the biggest problem is having too much money, not too little. For those who see little opportunity for a better life through hard work or entrepreneurship, these dreams are something they are happy to pay for.

Playing the lottery “is about the possibility of financial prosperity or abundance,” one Georgia gambler told me. “It’s all about hope.”

4. Players aren’t the only ones who turn to gambling in hopes of hitting the jackpot.

Like gamblers hoping for a payout, states legalized lotteries trying to hit a jackpot of their own. Between 1963 and 2018, voters and policymakers in 45 states bet on betting. They enacted lotteries because they believed gambling offered a way to fund public services without imposing new taxes.

“Despite decades of disappointment, not only did hopes for a tax-free jackpot endure, they paved the way for other forms of gambling.”

As post-World War II prosperity evaporated, states needed more money. Reluctant to pay more taxes, voters and legislators of nearly every political persuasion were taken with the prospect of tax-free gambling income.

Over time, hopes for lottery revenue gradually shrank. In the 1960s, lotteries were seen as a salve for entire state budgets. When revenue expectations proved to be too high in the 1980s, they were presented as a solution for a single budgetary area, like education or public parks. That also proved to be too ambitious. By the 1990s, lotteries arrived in southern states carried by the promise that they would fund specific programs, like a college scholarship or prekindergarten.

In the course of just 30 years, lotteries went from being seen as a budgetary cure-all to the funder of a single-state program.

States have remained all-in. Despite decades of disappointment, not only did hopes for a tax-free jackpot endure, they paved the way for other forms of gambling. Most recently, sports betting has enticed a whole new generation of lawmakers to the promise of a tax-free revenue jackpot.

5. Most of the money does not benefit popular public programs.

In one of my favorite lottery commercials, unsuspecting New Yorkers buying a lottery ticket are greeted by a small child, then a choir full of happy children, all thanking them for their purchase. This is the perception that state lottery commissions want to create: that playing the lottery is a good deed. The idea is that even if you don’t win, you should feel good about playing because public lotteries do good.

The problem is that lotteries do much less good than people think. Last year, for every dollar spent on lottery tickets, an average of 29 percent went back to the state beneficiary. Around half the money, in some states as much as 70 percent, goes to prizes.

“Most players seem just fine with less money going to the state, more money to prizes, and lower odds of winning.”

States used to have a much bigger cut, but over the years, players have come to expect bigger and bigger jackpots. Huge jackpots are only possible by lowering the amount that goes to the state, or by reducing the odds of winning.

States know their advertising can’t promise a windfall, as this would quickly leave them with millions of disappointed and impatient bettors. They instead focus as much as they can on the social good they do. Their messaging always emphasizes the amount they gave to the state, without putting that number into the context of total revenue from taxes. Lotteries usually account for just 3 percent of total state income.

For their part, most players seem just fine with less money going to the state, more money to prizes, and lower odds of winning. After all, it is hard to tell the difference between 1-in-3 million, 1-in-30 million, or 1-in-300 million odds of hitting a jackpot. It is easy, however, to see the difference between winning $30 million, $300 million, or $1.3 billion. The state’s cut has shrunk in hopes of keeping players interested. Like most lottery players, state officials have spent decades hoping for what they believed was an inevitable lottery windfall. Their unwavering hope is for a jackpot that will, against all odds, arrive one day soon.

To listen to the audio version read by author Jonathan D. Cohen, download the Next Big Idea App today: