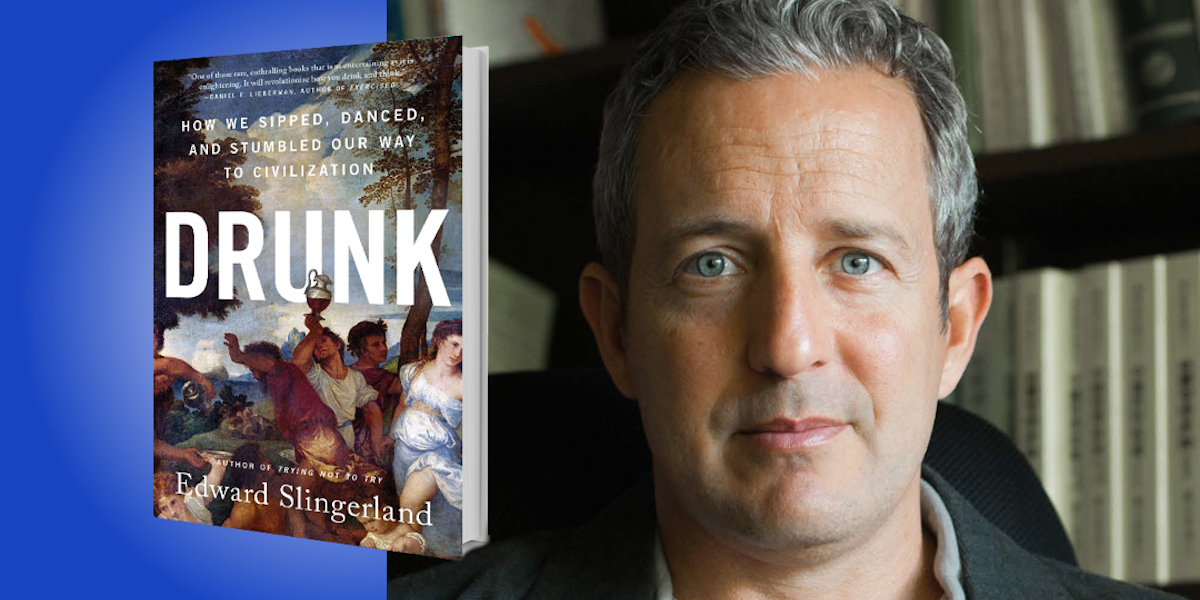

Edward Slingerland is a distinguished university scholar and professor of philosophy at the University of British Columbia. His last book, Trying Not to Try: Ancient China, Modern Science, and the Power of Spontaneity, was named one of the best books of 2014 by The Guardian and Brain Pickings.

Below, Edward shares 5 key insights from his new book, Drunk: How We Sipped, Danced, and Stumbled Our Way to Civilization. Listen to the audio version—read by Edward himself—in the Next Big Idea App.

1. Beer before bread.

The standard story we’ve been told about the origins of human alcohol making is that, at some point, humans figured out agriculture, settled down, and started growing crops. Then sometime after that, we noticed that if we left these grains sitting around in some water—maybe we left some sourdough starter a couple of days too long—it turned into something interesting to drink. In this view of the past, the discovery of beer was an accident, a by-product of agriculture.

When you look into the archeological record, however, you see that it’s actually the other way around.

Some archeologists now believe that the desire to make more and better beer encouraged hunter-gatherers to settle down and focus on domesticating plants. Throughout the world, the first domesticated crops weren’t particularly good for making food, but they were excellent for making intoxicants.

“Some archeologists now believe that the desire to make more and better beer encouraged hunter-gatherers to settle down and focus on domesticating plants.”

2. Our taste for alcohol is no accident.

The standard scientific story is that human vices, including our taste for alcohol, are evolutionary mistakes. When it comes to alcohol, the dominant theory is that alcohol hijacks our brains—that when we drink, we get a neurochemical reward for no good reason. But there are two problems with this view.

First, drinking alcohol is incredibly costly; it’s addictive, hurts your liver, raises your cancer risk, and causes social problems. And second, despite these costs, we’ve been drinking alcohol for an incredibly long time—at least 20,000 years. This means that there are functional benefits that outweigh the costs, and that explains why our taste for alcoholic beverages has stayed in our gene pools and cultural repertoires for as long as they have.

3. Alcohol is a muse.

There’s a widespread and ancient association between alcohol and the arts. And empirical evidence says that association exists for a good reason: alcohol helps us be more creative.

Our ability to think laterally and solve problems requiring big, creative leaps improves when we reach a blood alcohol content of about 0.08 percent—where we land after about two drinks. In that state, our prefrontal cortex (PFC) relaxes. Now, the PFC is an essential part of our brain; it’s what allows us to stay focused, remain on task, delay gratification, and do all the things we have to do as grown-ups and as successful human beings. The problem with the PFC is that by allowing us to focus in a laser-like fashion, it prevents us from seeing unusual things and making unusual connections, which is what creativity is all about.

“Our ability to think laterally and solve problems requiring big, creative leaps improves when we reach a blood alcohol content of about 0.08 percent—where we land after about two drinks.”

4. The chemical handshake.

Creating bonds between unrelated groups is a crucial function of alcohol. Drinking down-regulates the function of the PFC, making it harder to lie. It also allows emotions, desires, and thoughts that would normally get filtered by the conscious mind to come out. That’s why, when someone is drunk or at least mildly inebriated, we see a truer version of them.

Alcohol also boosts endorphins and serotonin, which makes us like other people more; we find them funnier, smarter, and more attractive. We also find ourselves funnier and more attractive when we’ve been drinking. And this helps with sociality—it increases interpersonal bonding, and increases the sense of being part of a group and having a group identity.

5. Alcohol has been very useful in the course of human history.

For most of human history, we drank relatively weak beers and wines. These typically clocked in at about 3 to 5 percent ABV. At these levels, you can drink socially and stay in that sweet spot of about 0.08 percent blood alcohol content, which is where most of the benefits from alcohol come from.

But recently (from an evolutionary perspective), we figured out a way to make alcoholic beverages incredibly more potent through the process of distillation. Suddenly, we had access to substances that bypassed the limits of natural fermentation. We’re just not well equipped, biologically or culturally, to deal with alcohol in such a potent form.

This problem of distillation is exacerbated by isolation. Drinking has always been communal and ritually regulated. Throughout most of human history, it was rare for a person to have private access to alcohol; the only way you would get access would be in a public ritual. The presence of others, and the presence of ritual restrictions and guidelines on when you can drink and how much you can drink, helped people guard against excess. Nowadays, we can have enough alcohol in our homes to kill an entire village of people—and we can consume as much of it as we want. This is a dangerous development.

To listen to the audio version read by author Edward Slingerland, download the Next Big Idea App today: