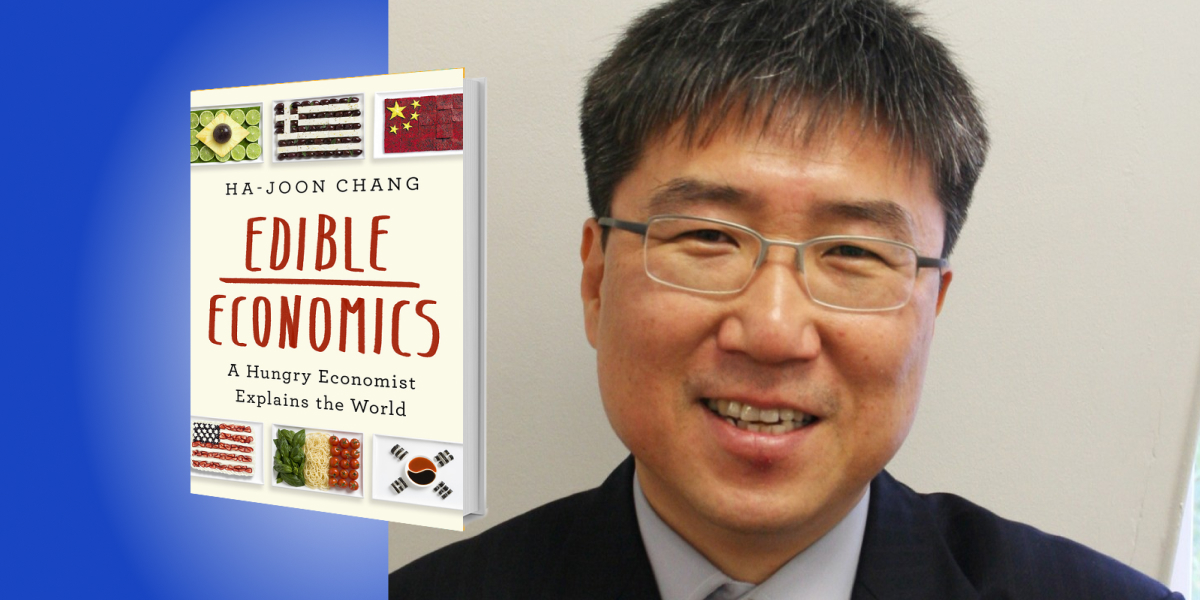

Ha-Joon Chang is a Professor of Economics at SOAS University of London and one of the world’s leading economists. His books include Economics: The User’s Guide, Bad Samaritans, and the international number one bestseller, 23 Things They Don’t Tell You About Capitalism.

Below, Ha-Joon shares 5 key insights from his new book, Edible Economics: A Hungry Economist Explains the World. Listen to the audio version—read by Ha-Joon himself—in the Next Big Idea App.

1. Everyone needs to learn economics.

A lot of people think economics is boring, difficult stuff, only needed by professional economists. However, we all need to learn at least some economics because, in a capitalist society, nothing is free from it. Economics is in jobs, mortgage payments, and taxes, but also libraries, the teaching of ancient languages in universities, and the preservation of cultural heritage.

I have even met some British people trying to justify the monarchy in terms of the tourist revenue it allegedly generates. I am not a monarchist, but what a demeaning way to defend an institution that you think is at the foundation of your society.

So, in a capitalist society, democracy is meaningless unless every citizen knows at least some economics. Otherwise, voting in elections becomes like voting in a talent show. I remember a lot of Americans voting for George W. Bush in the 2000 presidential election, saying that he “looks like a guy I could have a beer with.” What a criterion to elect someone for the most powerful political office in the world!

Having told you that we all need to learn economics, I realize that many people find economics too dry or complicated—that’s where Edible Economics comes in.

2. Economics is not that difficult.

In my previous book, 23 Things They Don’t Tell You About Capitalism, I stuck my neck out and said that 95 percent of economics is common sense, only made to look difficult because of jargon, math, and statistics. I also said that even the remaining 5 percent can be understood if explained well. I believe that anyone with a secondary school education can understand most of economics.

“In a capitalist society, democracy is meaningless unless every citizen knows at least some economics.”

Seemingly complicated economic subjects like international trade, automation, inequality, and climate change are all understandable if explained in a user-friendly way.

3. Talking about food is a nice way to get interested in economics.

However user-friendly the explanations are, many people don’t feel motivated to learn about economics because they find the subject rather dull.

I try to bribe my potential readers into thinking about economics by wrapping dry economic arguments in succulent food stories. Food is so fundamental to our survival, identity, and happiness that most people are interested in it. Talking about food is a natural way to draw people in—especially if you want to eventually talk about things that people think are boring.

Each chapter of my book is named after a food item (coconut, okra, chocolate, garlic, chili, you name it) and starts with some stories about that food item. But before you know it, the food stories are transformed into economic stories through what I call The Simpsons approach to writing.

All Simpsons episodes start with a short, wacky opening story, usually involving Bart Simpson. That story may turn out to be crucial for the main story in the episode, but it may prove to be totally irrelevant. It’s that kind of storytelling.

4. Having a more open mind towards diversity is the best way to have a more interesting and healthier diet.

The food stories in the book are diverse. Sometimes they are about the origin and the spreading of the food item in question, often through economic processes, like global trade, migration, slavery, and colonialism. Sometimes these stories are about the significance of the food item in some culture or historical events. Or they could even be about my personal relationship with that food item.

However, one thing that emerges from all these stories is that a diverse food culture, based on an open mind to new things and experimentation, is what makes our culinary life interesting and healthy.

One illustration comes from my own experience of the changes in British food culture. In 1986, I moved from my native South Korea to Britain, to do my graduate studies. At the time, food in Britain was awful—everything was overcooked and bland. People were afraid of new things. They refused to eat “foreign food.”

“A diverse food culture, based on an open mind to new things and experimentation, is what makes our culinary life interesting and healthy.”

At least for me, the British food scene in the 80s was epitomized by the pizza chain called Pizzaland, which offered customers an option to have their pizzas topped with a baked potato in case they needed a security blanket in coping with foreign food.

Today, the British food scene is totally different. It has become one of the most diverse and exciting places to eat in the world.

How did this great transformation happen? My theory is that sometime in the late 1990s, British people had a collective epiphany that their food sucks. Once they gave up their own food, they opened their mind to everything. There was no reason for them to favor Mexican over Korean or Italian over Ethiopian.

In other words, by having an open mind, British people achieved one of the greatest culinary transformations for the better in human history.

5. There are different ways of “doing economics.”

From the 1990s, my food universe was rapidly expanding. Partly because of the British culinary revolution, but also because I started getting exposed to many different culinary traditions due to my travel to developing countries for my work—I am what they call a “development economist.”

While this was happening, unfortunately, my other universe, the universe of economics, was being sucked into a black hole. Until the 1970s, the world of economics resembled today’s food scene in Britain. There were several different schools of economics, each of them proud of their own heritage but having to compete with each other, learn from each other, and create “fusion” theories.

Unfortunately, from the 1980s, one school of economics, known as the Neoclassical school, became completely dominant, making the intellectual scene in economics like the food scene in Britain before the 1990s: lacking in diversity and stagnant from lack of competition, and lack of opportunities for fusion.

I am not saying that Neoclassical economics is particularly bad. Like all other schools of economics, it was built to explain particular things on the basis of certain ethical and political premises, so it is very good at some things but very bad at other things. The problem is the almost total dominance of one school. This has limited the scope of economics and created theoretical biases.

“The dominance of economics by one school has made economics limited in its coverage and narrow in its ethical foundation.”

For example, Neoclassical economics regards self-seeking as the most important (if not the only) aspect of human nature. With the dominance of Neoclassical economics, self-seeking behavior has been normalized. People who act in an altruistic way are derided as suckers or are suspected of having ulterior motives. But Behavioralist or Institutionalist economic theories would tell you that human beings have complex motivations, of which self-serving is only one of many.

For another example, Neoclassical economics starts its analysis after taking the existing distribution of income, wealth, and power as given, so it is inherently bad at challenging the status quo. So, the dominance of economics by the Neoclassical school means that economics is now playing the role of Catholic theology in Medieval Europe. It has become a doctrine that tells people that things are what they are because they have to be, no matter how unjust and wasteful they may look.

In the same way that Britain’s pre-90s refusal to accept diverse culinary traditions made the county a place with a boring and unhealthy diet, the dominance of economics by one school has made economics limited in its coverage and narrow in its ethical foundation.

There are many different ways of doing economics and our understanding of the economic world will become so much better if all the diverse ways of thinking about the economy co-exist, interact with each other, and learn from each other.

To listen to the audio version read by author Ha-Joon Chang, download the Next Big Idea App today: