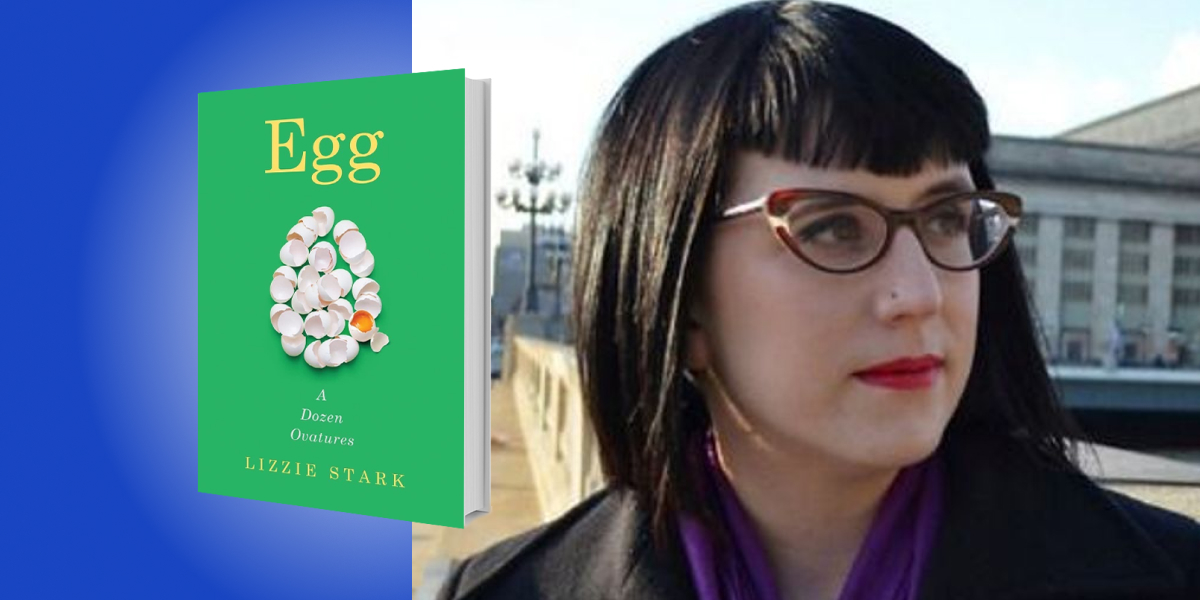

Lizzie Stark is a participation designer and the author of two nonfiction books, Pandora’s DNA and Leaving Mundania. Her writing has been featured in the Washington Post, the Daily Beast, io9, and the Philadelphia Inquirer, among other publications.

Below, Lizzie shares 5 key insights from her new book, Egg: A Dozen Ovatures. Listen to the audio version—read by Lizzie herself—in the Next Big Idea App.

1. Eggs are everywhere, and they are protean.

You know the saying, “When life gives you lemons, make lemonade.” Well, when evolution gave us eggs, we transformed them into lots of different things. During the colonial era in the Philippines, for example, the Catholics built huge stucco churches and used protein from egg whites to strengthen their building materials. As a result, the local women found ways to use yolks in their baking, incorporating them into iconic snacks and desserts.

About 60,000 years ago, when prehistoric people managed to snatch ostrich eggs, they cooked the contents but preserved the shells as perfect canteens. Fitted with a grass or beeswax stopper, these canteens held about one liter of water, kept cool by the pores in the eggshell. They carved their canteens with patterns that resemble railroad tracks and checkerboards, which may represent the world’s oldest evidence of abstract human thought. Over the years, eggs have been magic charms, art objects, mythic origins, the objects of Freudian obsession (primarily for British men), and so much more.

2. Eggs are valuable.

You think egg prices are high today? During the gold rush era, an exploding population teamed with an infrastructure that couldn’t keep up, leading to food shortages. At the same time, locals couldn’t figure out how to keep large flocks of chickens in the area. Chicken eggs went for $12 to $36 per dozen—or between $400 and $1,200 per dozen accounting for inflation. Some enterprising businessmen figured out that the nearby Farallon islands, inhospitable to humans but packed full of sea birds, could churn out hundreds of thousands of dollars of passable eggs so naturally, an armed gang struggle ensued. Over a few decades, the eggers decimated 95 percent of the local murre population in the name of eggs.

“Eggs have been magic charms, art objects, mythic origins, the objects of Freudian obsession (primarily for British men), and so much more.”

Egg sales have been a vehicle for empowerment for people of color and women. During the antebellum era, people who were enslaved were allowed to own chickens and sell the birds and their eggs for a profit. They could then afford to buy needed goods or even purchase their freedom. Likewise, since chickens ate table scraps and hung out near the house, raising the birds was also considered the domain of farm women. They would barter with the eggs for needed supplies or sell them to create their “egg money,” money of their own that could be used exactly as she wished.

Even now, international development circles consider chickens to be the ATM of the poor. As Melinda French Gates wrote, flocks provide eggs as well as meat that can be sold and consumed. Plus, the investment is one that can be liquidated in a hurry.

3. Eggs are a tasty, democratic food.

Eggs are the ultimate chef’s test. According to legend, the hundred folds in a chef’s toque represent mastery of a hundred egg dishes. When chef Jacques Pepin was asked about eggs, he quoted an old French cooking bible, “The egg is to cuisine what the article is to speech.” That is, you can’t do a thing without them. Eggs are also one of the oldest foods and more than 99 percent of the world’s eggs are non-poisonous and edible.

They are really two ingredients in one: the yolk is packed full of fatty spheres, while the white is a nearly fatless substance made of balled-up proteins. You can use them separately or together, and by manipulating the fat spheres and the way those proteins tangle, you can create a huge variety of textures, from loose custard to spongy crisp meringue, and every texture in between.

4. Eggs are a valuable analog for the human body.

Early experiments around space sent various types of eggs up in high-altitude balloons to determine the effects of cosmic rays on the human body. This helped scientists discern whether it was safe to send humans to space.

“Eggs are also one of the oldest foods and more than 99 percent of the world’s eggs are non-poisonous and edible.”

In the 1980s, teenager John Vellinger noticed that his family’s chickens rotated their eggs daily to counteract the effects of gravity and wondered what would happen to eggs in a low-gravity environment, like space. Over several years, he designed an experiment to send an egg incubator to space that won one of NASA’s national space competitions. Part of the condition of winning was that they hooked him up with a corporate sponsor, in this case, Kentucky Fried Chicken. With his industry partner Mark Deuser, the two designed an experiment to shoot fertilized eggs into space. Their experiment discovered that embryos had to be past a certain point in their development to be viable after space flight. The first chicken hatched from their collection of eggs was named Kentucky and sent to live out its life in the Louisville Zoo. The two of them went on to found a company that builds gear for scientific experiments in space.

5. Eggs are an excellent medium for art.

For millennia, eggs have been used in art. Eggs are great at binding to things, as anyone who has tried to wash dried raw egg off crockery knows. Mix a pigment with egg yolk and you’ll get tempera paint, used as far back as the 1200s. The egg white, mixed with pigment and dried, also makes cake paints. Early photographers frothed egg white with salt and used it to create the original glossy coated print. Whole eggshell is an excellent canvas for resistance painting; Ukrainian women have long used them to make beautiful and intricately decorated pysanky, using a wax resistance method. Ground-up eggshell works as a paint extender and texturizer.

One of the best forms of art involving eggs was probably modern British artist Sarah Lucas’s participatory piece 1,000 Eggs: For women. Women and people wearing at least one item of stereotypically feminine clothing pelted eggs at a specially treated gallery wall. Run several times in different galleries across the world, you can appreciate the visual of women hurling the world’s most precious and worthless cell at a gallery wall. It’s a glorious subversion of our culture’s attitude toward feminine caregiving: Women having control of their own eggs and deciding what to do with them, and using them to make art. What could be better than that?

To listen to the audio version read by author Lizzie Stark, download the Next Big Idea App today: