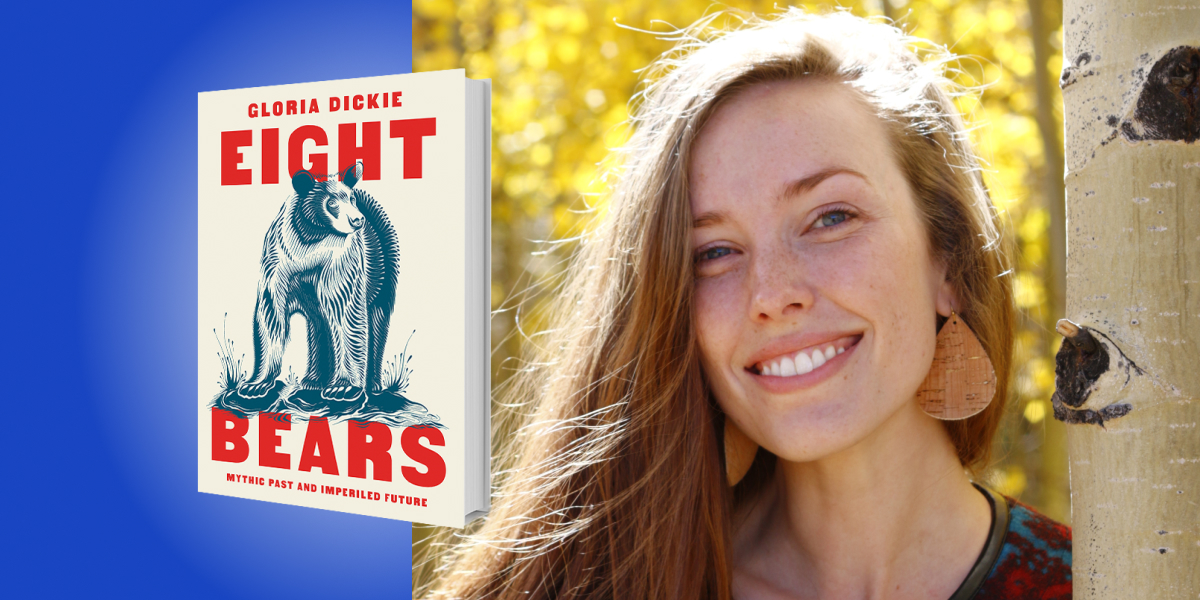

Gloria Dickie is an award-winning journalist and is currently a global climate and environment correspondent at Reuters News Agency. Her writing has been published in the New York Times, the Guardian, National Geographic, Scientific American, and Wired, among others. She was nominated for a National Magazine Award, was named a finalist for the Livingston Award for Young Journalists in international reporting, and has served on the board of the Society of Environmental Journalists.

Below, Gloria shares 5 key insights from her new book, Eight Bears: Mythic Past and Imperiled Future. Listen to the audio version—read by Gloria herself—in the Next Big Idea App.

1. Humans display a surprisingly high level of tolerance for bears.

One thing that has stood out to me when reporting around the Mountain West on human-wildlife conflict has been people’s attitudes toward bears compared with other predators. Ranchers and hunters always showed far more tolerance toward grizzly bears than they did wolves. Mention a wolf and the whole mood darkens. But mention a bear, and they’ll often share a fond anecdote with you. Why?

The first animal most humans encounter in any form is the teddy bear. Perhaps this crib-side companion has allowed us to view bears with a sense of kinship.

Also, we can consider the stories we tell about predators. Think about the classic fairytale antagonists. The Big Bad Wolf reigns supreme in “Little Red Riding Hood” and “The Three Little Pigs.” But I’ve yet to encounter a tale featuring a villainous bear, though brown bears likely still roamed Germany’s Black Forest—the ground zero of fairy tales—when the Brothers Grimm were spinning their most famous yarns. In “Goldilocks and the Three Bears,” arguably the most notable piece of bear folklore, our ire is not directed toward the bear family, but rather the intrusive human.

2. Humans have—and can again—make room for big animals on the landscape.

Governments once issued bounties on the Lower 48’s fifty thousand grizzly bears with the aim of eradication. Wherever they were found, bears were trapped, shot, and poisoned. Wilderness was slowly sanitized. Grizzly populations dwindled in concert. State by state, the bear disappeared: Texas in 1890; New Mexico in 1931; Colorado in 1953. By the mid-20th century, grizzly bears had almost been expunged from the continental United States.

Even black bears were pushed to the brink of local extinction in many places. Fewer than twelve individual bears were thought to have remained in Mississippi, for example.

“By the mid-20th century, grizzly bears had almost been expunged from the continental United States.”

But eventually, we reversed course, choosing to champion bears instead of killing them. Grizzlies now number as much as 2,000 in the lower 48 states, up from just a few hundred in the 1970s when they were listed under the Endangered Species Act.

We can recover large predators when we want to.

3. Bears hold a special place in northern cultures.

Growing up in Canada, I’d assumed that many countries had a bit of an obsession with bears. The colonizers of Canada once considered naming it Ursalia, meaning place of bears. But that obsession is not the case for much of the world. The culture around bears is a pretty uniquely Northern Hemisphere phenomenon, despite bears—like the sun bear and Andean bear—occurring below the equator.

Scholars even have a name for this: the circumpolar bear cult tradition, which posits that veneration of bears is a defining characteristic of cultures in the Northern Hemisphere. This veneration spreads from the Sami in Scandinavia to the Inuit in Canada. As one anthropologist put it, “Since Paleolithic times, most ursids have been a source of potent ritual symbols,” often offered as a sacrifice so that humans may communicate with the spirit world.

But in the tropics, it’s all about big cats.

4. Our relationship to pandas is unique within the animal kingdom.

The cultural connection between people and pandas seemed to transcend not only our relationship with the other seven bear species but perhaps with any other wild animal. Indeed, the panda may be the only creature in the animal kingdom that today has been spared the worst of human nature. Beloved beasts like tigers, elephants, and rhinos are relentlessly exploited for their skins, tusks, or horns. Even man’s best friend—the dog—occasionally finds himself on a menu.

Not pandas. Despite their cute and cuddly appearance, they’ve yet to be abducted into the exotic pet trade.

“The panda may be the only creature in the animal kingdom that today has been spared the worst of human nature.”

That wasn’t always the case. Pandas were once killed for their pelts. But in the 1960s, Mao Zedong’s party banned all hunting of the bear. Anyone caught poaching a panda faced jail time or, under grave circumstances, the death penalty. In 1993, two men were handed death sentences in a South China court for trafficking three panda pelts. A few years later, a farmer in Southwest China was sentenced to twenty years in prison for killing giant pandas and selling their pelts. In 2017, China changed the maximum penalty for panda poaching and smuggling to “not less than 10 years or life imprisonment and a forfeiture of property.”

If only other vulnerable species were treated with such respect.

5. Saving bears can’t always be done on the ground.

There’s a tendency in conservation to only focus on protecting what’s on the ground, since many species are threatened by habitat loss. But in the case of many of the world’s bear species, there are larger forces at play.

There’s no way for us to simply conserve or set up national parks around Arctic sea ice. The polar bear cannot be saved simply with measures to address habitat loss. Its future depends on global action on climate change—and we are not heading in the right direction.

At this point, scientists don’t expect many of the world’s 19 polar bear populations to persist far beyond the end of this century. The Andean bear, too, is seeing its cloud forest home shift to a higher altitude, due to climate change. They, too, face an uncertain future if they’re unable to adapt to using lower elevations in the Amazonian forest.

To save species most threatened by climate change, it will truly take a global effort.

To listen to the audio version read by author Gloria Dickie, download the Next Big Idea App today: