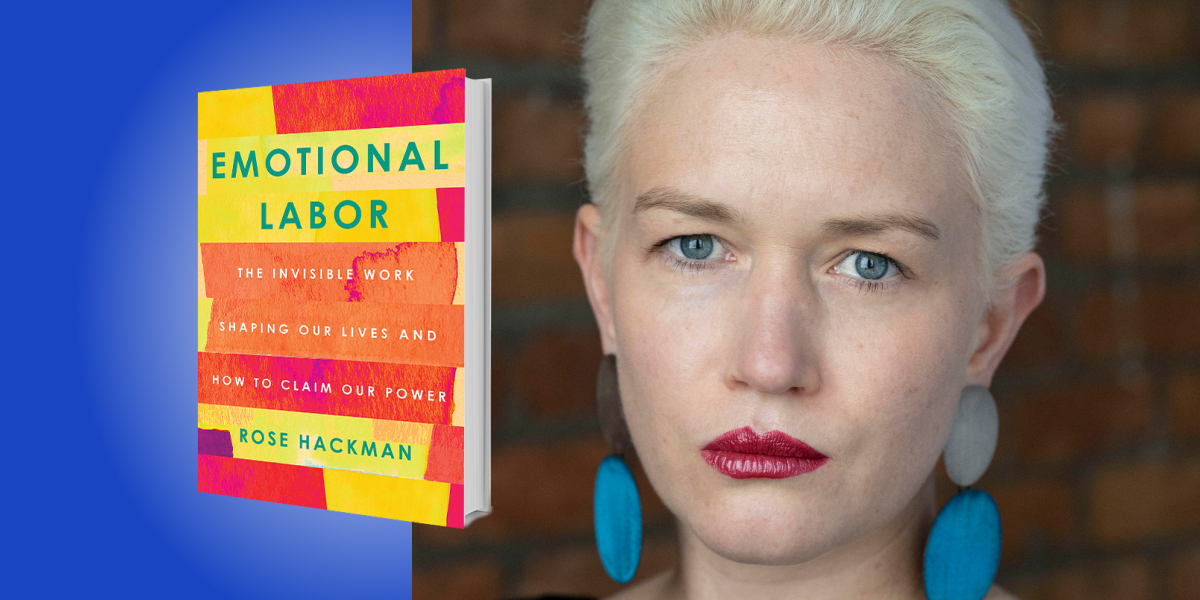

Rose Hackman is a journalist who has been published in The Guardian and the Associated Press. She received her undergraduate degree from University College London and she graduated with a master’s degree in Human Rights from Columbia University, where she focused on social and economic rights violations in the United States.

Below, Rose shares 5 key insights from her new book, Emotional Labor: The Invisible Work Shaping Our Lives and How to Claim Our Power. Listen to the audio version—read by Rose herself—in the Next Big Idea App.

1. Emotional labor is a real form of work.

It pains me that it needs to be stated, but it does. Emotional labor is the work of editing the expression of your emotions in order to have an effect on the emotions of others. This is a real form of work.

Just like intellectual labor, physical labor, and creative labor, emotional labor takes time, effort and skill to be performed. It is a key form of work that we see as a core requirement across many service industry jobs. A customer care representative is not just there to solve your problem, they are there to manage your emotions. A nursing assistant is providing emotional labor as the central part of their job. A flight attendant is there not so much to give out snacks and drinks, but to convey feelings of safety and care. In private, this form of work is the invisible, highly feminized work expected of girls, women, wives, and mothers.

2. Emotional labor is fundamentally not about gender, it’s about power.

As things stand, emotional labor is a feminized form of work. That is to say, in private settings, we expect it from women, and it is widespread across feminized industries. In white-collar settings, still deemed masculine, we expect women to provide emotional labor on top of the actual requirements of their jobs.

But emotional labor is not inherently gendered. The idea that women are “emotional creatures” and men are “rational” is an entirely erroneous, patriarchal dogma held to keep gendered hierarchies in place. All humans, regardless of gender, perceive the world through their emotions. All humans, regardless of gender, are relational; we all need connection to one another in order to survive. Studies across neuroscience and psychology clearly show that the expression of empathy is tied to motivation. Given the right motivation, all genders are equally able to put empathy into action, to do emotional labor.

Currently, the distribution of emotional labor is tied to power. It is the work of whoever is cast as inferior. Someone with less power in a situation will be expected to cater to the emotions of people with more power. The easiest way to think of this is within an amorphous company setting. A boss will not have to cater to the feelings of the people who work underneath them, whereas a junior associate will have to cater to the feelings of those above them.

“Given the right motivation, all genders are equally able to put empathy into action, to do emotional labor.”

If you complicate this with categories like race and gender, you will find that a Black person will be expected to cater to the emotions of white people in a white setting—to do that emotional labor—because of white supremacy, often regardless of rank. Women, also, because of patriarchy, are expected to put their emotions to work for the experiences of men and society at large chronically.

Within this system, emotional labor ends up being somewhat of a negative self-fulfilling prophecy. It is a form of work offloaded onto people with less power, but it is also a form of work that ends up serving as an artificial signifier of lower status.

3. Emotional labor is highly valuable.

Here is the catch though: emotional labor is highly valuable. It is an essential form of work that keeps our society and economy running.

Our economy and society rely on the unpaid emotional labor of millions who care for and nurture entire families and communities, including children and the elderly. That nurturing additionally extends to workers, people out of work, and everyone in between. Our brutal public policies rely on armies of emotional laborers to buffer the consequences of mass incarceration and a military state.

In our formal economy, emotional labor is a central part of millions of jobs, including the kinds of jobs that are going to be hard to automate. This includes jobs across healthcare, social services, and education. In white-collar industries, emotional labor—which is the activation of emotional intelligence—is only going to grow in importance, as intellectual tasks become automated.

In very real ways, emotional labor is the future of work. But up until now, because of its invisibility, we have refused to acknowledge let alone value emotional labor. This desperately needs to change.

4. Fake morality keeps emotional labor exploitative.

Part of the way in which we keep emotional laborers from accessing the real value of their work is by telling them that monetizing emotional labor is a deplorable, vulgar, and even immoral act. This is an act of systemic gaslighting. Emotional labor is already monetized, but the people pocketing the profits are not the workers, but the ones for whom the work is being done.

“This is an act of systemic gaslighting.”

Seeing and valuing emotional labor is not a sign of neoliberalism gone amok. Not seeing or valuing emotional labor and, therefore, enabling a coercive system that forces feminized and racialized workforces to work for little to nothing is.

Formerly acknowledging that emotional labor has value is not a threat to civilization. The ongoing lack of acknowledgment is the threat.

5. Love and power should not be considered polar opposites.

The flip side of our current crisis of loneliness and isolation is a crisis of emotional labor.

Life expectancy has been declining in the United States since 2014. This is, in large part, because of deaths of desperation, concentrated among men. Prizing value systems that encourage hierarchies and domination over emotionality is deadly for women, but it is also deadly for men. Not valuing or centering emotional labor does not just make losers out of women as they are cast as the de facto workers for men. Devaluing emotional labor also makes losers out of men, who are cut off from their full, emotional selves. This has consequences on their relationship to themselves as well as their relationship to others.

We need a radical paradigm shift in our value system. Love in action, or emotional labor, should be at the heart of this new value system, no longer on its hidden margins. In many ways, this would not be a new system at all, but a harkening back to how living in a community began in the first place.

Anthropologists and historians of money consistently find that the origin of money is not barter, but objects that mark relationships. By marking a relationship, an object was signifying an open-ended IOU between people. It was marking a tie and the expectation of mutual and open-ended emotional labor that could lead to any number of exchanges. Once you understand this, the question is no longer whether emotional labor should be compensated, but it becomes the epiphany that once upon a time emotional labor was value.

“The beginning of civilization as we understand it was not competition, war, or hierarchy but empathy in action: emotional labor.”

Famed anthropologist Margaret Mead recounted the birth of civilization not with agriculture, a clay pot, or a tool, but a healed femur. A healed femur, she claimed, was the sign that someone had been willing to put their immediate needs to the side to care for an injured person so that they might heal. “Savage societies could not afford such pity,” she said. To her, the beginning of civilization as we understand it was not competition, war, or hierarchy but empathy in action: emotional labor.

Ultimately, emotional labor should be spread out even as it is valued. Doing so would not only be just, it would create benefits for all. Truly valuing emotional labor would redress injustices against women, and it would also create a new incentive system for men that would ultimately hugely benefit them too. More connected, empathetic men with stronger relationships live longer.

When dynamics reverse, and emotional labor is done by people and groups who previously held tremendous power towards people who have had less, this form of work even has a restorative, reparative quality. This systemic recalibration is one Martin Luther King, Jr perfectly called for in his book Chaos or Community.

“One of the greatest problems of history is that the concepts of love and power are usually contrasted as polar opposites. Love is identified with a resignation of power and power with a denial of love. What is needed is a realization that power without love is reckless and abusive and that love without power is sentimental and anemic. Power at its best is love implementing the demands of justice. Justice at its best is love correcting everything that stands against love.”

To listen to the audio version read by author Rose Hackman, download the Next Big Idea App today: