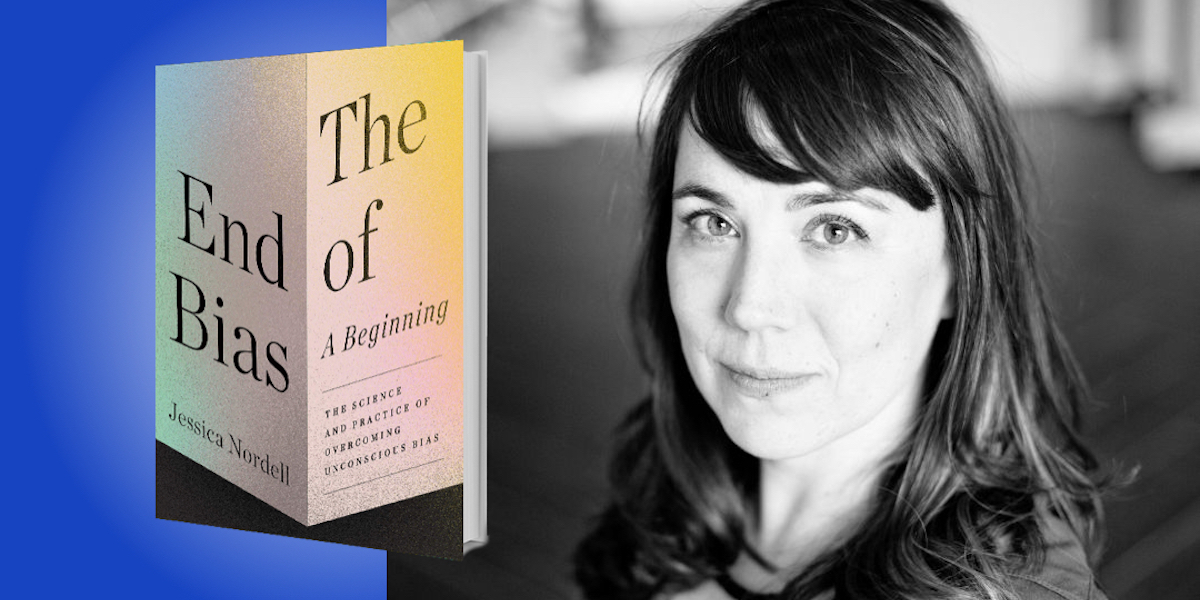

Jessica Nordell is an award-winning science and culture journalist whose work has appeared in the New York Times, The Atlantic, the Washington Post, and elsewhere. Her book looks at evidence-based approaches to tackling bias that’s unconscious, unintentional, or just unexamined. She explains that this kind of bias is pervasive, and she provides essential, proactive steps to combat it.

Below, Jessica shares 5 key insights from her new book, The End of Bias: A Beginning: The Science and Practice of Overcoming Unconscious Bias. Listen to the audio version—read by Jessica herself—in the Next Big Idea App.

1. Bias can interfere with the very best of intentions.

Unconscious bias develops through a series of invisible steps. Growing up, we learn notions from our culture about which categories people fit into, and we absorb associations and stereotypes about those groups. When we encounter a person who fits a category lurking in our memory, all those associations spring into action and start to influence how we interact, feel, and think—and it often happens without us realizing it, spontaneously and automatically. We believe ourselves to be egalitarian, but we act in ways that conflict with that.

Evidence of unintentional bias is everywhere: in education, criminal justice, policing, the workplace, healthcare, and more. There’s some debate about just how unconscious it is—maybe in some cases people really do intend to treat people harmfully—but most people have good intentions. They want to treat people well as a professional in their field, and in daily life. But evidence shows that people can still behave in biased ways.

A couple of chilling examples from healthcare: Black patients with vascular disease are more likely to have a limb amputated instead of limb-sparing treatment, relative to white patients—even after taking into account insurance status, disease severity, and hospital quality. A Mayo Clinic cardiologist shared that even when diagnosis is clear (as in a heart attack) and guidelines for care are clear (as in medication), women still receive inferior treatment. Doctors may not intend to treat people differently, but these unexamined patterns create harmful consequences.

“Even when diagnosis is clear (as in a heart attack) and guidelines for care are clear (as in medication), women still receive inferior treatment.”

2. Stereotypes, unfortunately, feel good.

There’s so much to say about the brain science of stereotyping and discrimination. Many of us have heard of confirmation bias—the idea that we seek out and pay more attention to information that confirms what we already believe to be true. But there’s another dimension to our desire to make sense of the world. If I stereotype you, I’m projecting an expectation about what you’re going to do or say, and what kind of person you’re going to be.

What the brain does with predictions is really interesting. If what we predict comes true, we sense a reward; it feels good. If our prediction does not come true, that can feel unpleasant. Research by Wendy Berry Mendes shows that people who interact with those who violate stereotypes respond as though experiencing cardiovascular threat. That’s how uncomfortable it can be to have predictions violated. This helps show how sticky stereotypes can be, as confirming them provides a form of positive reinforcement.

The good news is that there are a lot of approaches that work to tackle bias, and one place to begin is awareness. It sounds simple—just start noticing your own biases!—but it’s actually really hard. First, we have to be willing to accept the fact that we have the capacity to act in ways that conflict with our values. It’s also difficult to notice because the reactions happen so automatically. But it does get easier with practice, and this is where things get really interesting.

It’s like mindfulness, because the more you practice noticing your spontaneous reactions to other people, the more you have the chance to pause and ask yourself questions: Why did I have that reaction? Are there other explanations for a person’s behavior? Am I really sure this is true? One person told me that after reading this book, she felt like Neo stopping bullets in The Matrix—she started noticing her spontaneous reactions, and was then able to investigate them in real time.

So in short, attention to what’s happening in our own minds is the first step to combat bias.

“We have to be willing to accept the fact that we have the capacity to act in ways that conflict with our values.”

3. The concept of “the pioneer” disguises discrimination.

We tend to cheer on pioneers—the first woman to go to space, the first Latina in the field of chemistry. But this celebration conceals something really important. Being the first, or only, person of your identity in a department, field, or organization is not a role everyone wants or is suited to. The path can be lonely and alienating. Pioneers have to contend with others’ stereotyping and, sometimes, aggression. They have to perform in an environment that is harsher to them than to others. So, in addition to having all of the stated skills to do the job, a pioneer must have an additional set of skills and characteristics that have nothing to do with the actual job. We might call these “pioneer requirements.”

In engineering, for instance, the skills required for the job might be technical acumen, creativity, ability to work well in teams, and good communication. But the pioneers have to have all of these skills and be able to handle a lot of solitude, shrug off harmful comments, and navigate a culture that may be downright hostile. They have to contribute without necessarily feeling like they belong. Job skills and pioneer skills might even oppose one another: A job might require teamwork, but a pioneer might have to thrive alone. Pioneers have to fulfill these shadow requirements while performing at the same level as—or beyond—everyone else.

Homogeneous organizations artificially shrink the pool of candidates from underrepresented backgrounds. They require those candidates to possess not only the stated job requirements but the shadow skills, too. The number of people who possess both is exceedingly small. One complaint about affirmative action programs is that they artificially boost the number of individuals from underrepresented groups in a given school, organization, or company. But homogeneous environments artificially boost the number from the majority culture because they require a much smaller skill set from those individuals.

“In addition to having all of the stated skills to do the job, a pioneer must have an additional set of skills and characteristics that have nothing to do with the actual job.”

4. In organizations, the term “culture fit” may be a red flag—but it doesn’t have to be.

When people are being assessed for a job, they’re often looked at in terms of whether they fit into the culture. It’s an ambiguous bit of criteria, but can play a huge role in whether someone gets hired, promoted, or is seen as a great team member. Here’s why that’s a problem: We have a tendency to be drawn toward people who are like ourselves. There’s a term for it: homophily, meaning “love of the same.”

In fact, sociologist Lauren Rivera found that in professional organizations, people were more likely to hire someone who played a college sport if they played a college sport themselves, and they had even more preference for people who played the same college sport. So when we use “culture fit” to assess whether someone is a good candidate, it often means “a person who is like me.” What can we do instead? In any situation where people are being evaluated, use clear, objective, structured criteria whenever possible, and make sure everyone knows what those are.

5. Meaningful, collaborative connections with others can unwind discrimination.

Research shows that one way to reduce discrimination is by forming meaningful, collaborative connections with other people, especially to achieve a shared goal. For instance, one study found that when men who were from different castes in India played on the same cricket team, they were more likely to choose someone from a different caste as a future teammate, and also more likely to become friends with someone from another caste.

Working collaboratively with people of a different social identity changed the way these men acted, thought, and felt toward one another. When we get to know people on a deeper level, we start seeing other groups as more complex. One of the tricks the brain does is perceive our own group as wonderfully diverse, and groups we don’t belong to as homogeneous. It’s called “outgroup homogeneity.” As our understanding of others’ complexity grows, we develop new categories for people, and break down some of the generalizations and stereotypes that create room for harm and discrimination.

To listen to the audio version read by Jessica Nordell, download the Next Big Idea App today: