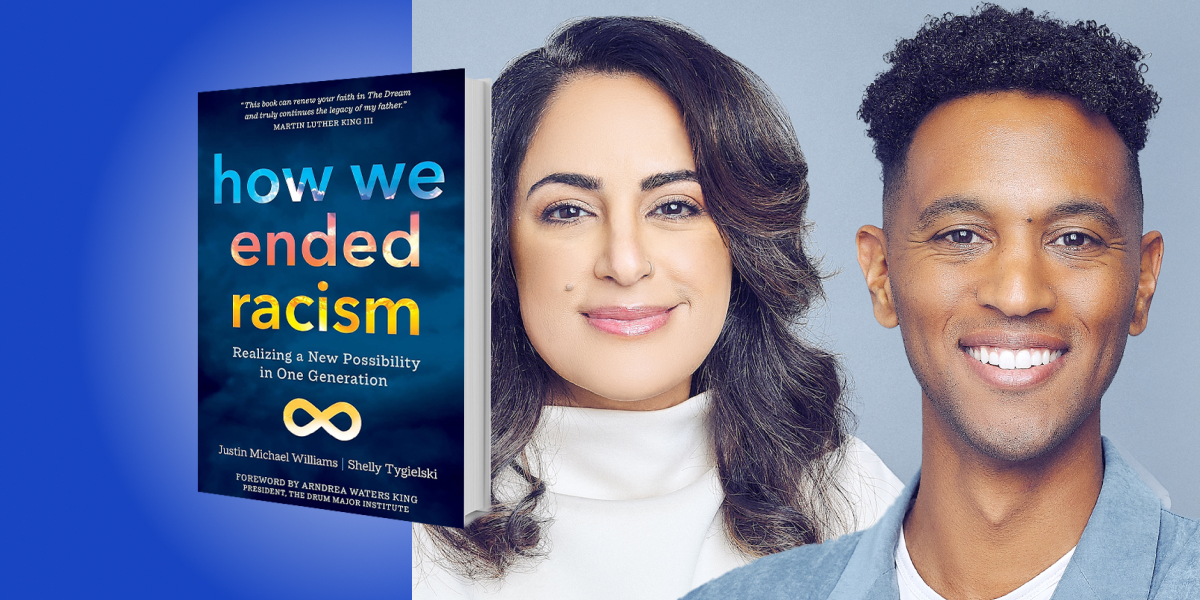

Justin Michael Williams is an author, keynote speaker, and Grammy-nominated recording artist. He is also the host of the “Motivation For Black People” podcast.

Shelly Tygielski is a trauma-informed mindfulness teacher, speaker, author, and activist. She founded the CNN Hero-featured global grassroots organization Pandemic of Love.

Below, co-authors Justin and Shelly share 5 key insights from their new book, How We Ended Racism: Realizing a New Possibility in One Generation. Listen to the audio version—read by Justin and Shelly—in the Next Big Idea App.

1. Being “anti-” will never work.

Fighting “against” racism will never work. It will only fight back. We must be fighting for something rather than fighting against something. When we are fighting against something, we often become even more disconnected from one another than when we started, because our only tether to one another is the problem itself. In fighting against a problem, it’s only a matter of time before we end up fighting each other, arguing over whose way of fighting the problem is better or more important. In this case, which is modeled many times throughout history, the persistence of circumstance prevails and we end up torn apart.

Using the model of “Creating From The Future,” we can instead create a future worth fighting for. Creating a future vision will give us something to walk toward instead of just focusing on what we’re fighting against or running away from. Although we may have different ideas on how to get there, the vision of a world without racism is our anchor.

2. You can’t “fix” racism, but ENDING it is possible.

Think about it. What the heck is “fixed” racism, anyway? Let us be clear: You don’t fix racism. You don’t improve racism. You don’t make it better. You end it.

We have learned through anthropology, neuroscience, sociology, and psychology that racism is not some automatic human condition that we’re born with. Although it’s hard for us to imagine, racism is not something that’s unavoidable. It’s not something that “just happens” as a result of putting a bunch of diverse people on a planet together. This is not our idea or opinion. It is widely respected and proven by science that racism itself is not “a given.”

“Racism is not something that’s unavoidable.”

In our research and focus groups, we discovered the Eight Pillars of Possibility, which are the eight conditions that would need to arise in society for racism to end. Understanding that racism is not “unavoidable” is key. The idea that racism is unavoidable would be like saying the Holocaust was unavoidable, or that American slavery was unavoidable, or refusing the LGBTQIA+ community the right to marry was unavoidable. There’s a real danger in saying something is unavoidable because we immediately absolve ourselves of taking responsibility to change it and allowing things to go on for far longer than they need to or should. We can teach people how to move beyond their skepticism to a deeper, more purposeful (and nuanced) form of truth.

3. We must build our cultural immune system.

Think of the idea of ending racism as a metaphor for our immune system. In order to have a healthy immune system, we can’t just fight sickness—we must also be proactive in cultivating wellness and good health. We invest in our health to build what the mindful researcher Dr. Amishi Jha calls “precovery” and “presilience,” so that when we encounter something toxic, our immune system is strong enough to fight it off. Thus, by cultivating health (not just fighting sickness), we are changing the conditions and context in which sickness tries to occur.

Look at ending racism the same way—we are not “fighting racism,” we are changing the conditions and context in which racism occurs. We must evolve our culture to be one that has an even better-equipped immune system to hold competing ideals—one that has practices, knowledge, and systems in place that make it hard for racism to show up. When and if it does show up, the immune system of our culture is strong enough to handle it.

The conditions we need to offer and teach need to create a culture (whether it’s a company, family, community, or society) that is strong enough to handle racism in a way that does not leave us in shambles, more distrusting of one another, or more divided. This is how we become the conditions required for racism to end.

We—each of us, individually and collectively—are the end of racism. When racism touches you, it ends. If enough of us learn the skills needed and take them into our individual areas of influence—with all of our fields of expertise, into all of our circles, and into all of our relationships—we can and will end racism, together.

4. You don’t have to be ashamed of your privilege.

Contrary to popular belief in many anti-racist and bias trainings, your privilege is not something to be ashamed of or silent about. We see it, instead, as your most authentic entry point to help the movement for change. If you are lucky enough to get out of a burning house before the fire department arrives and there are still others trapped inside the flames, your responsibility is to grab a hose and start dousing the house with water. Having privilege gives you the opportunity to hold more hoses.

Most of us have been so ashamed of our privilege that we choose to hide it. Thus, instead of getting out of the burning house and helping to douse the raging fire, we play small and pretend that we can’t hold any more hoses because we don’t want to “look too privileged” or “make it all about us.” In the meantime, the house is burning down with people trapped inside.

“Our task is not to raise children “without privilege” or who learn to hide it.”

Another way to understand this perspective on privilege is cross-generationally. We both grew up with a significant level of struggle, with Justin in a biracial low-income household, and Shelly as a Jewish immigrant. We both have worked hard to create better lives for ourselves and our families. Thus, our children, we anticipate, would be far more privileged than us. Of course, we wouldn’t want our kids to be ashamed of that, because we worked hard for them. Our task is not to raise children “without privilege” or who learn to hide it, but instead to raise our children into a culture that is actively ending racism so they can be the first children to never question whether they should hold hoses when they see a burning house. They will inherently understand that they have a moral responsibility to hold as many as their privilege allows them to hold, and they will take pride in helping as much as they can.

By taking this compassionate approach, we reorient our relationship from thinking privilege is something negative or something we should hide or be ashamed of. Instead, we can see privilege as a springboard, regardless of how we got it, as an access point to being of greater service.

5. Messy conversations are essential, here’s how to have them.

The best conversation skill we can teach you is the difference between calling forward and calling out. First, let’s make some distinctions. Calling out means publicly naming a wrong, an infraction, or a mistake. Calling out leads to cancel culture; cancel culture is ineffective and divides us further. The problem is that calling out typically gets infused with shame, blame, and guilt. It’s well documented in studies in the fields of psychology, anthropology, sociology, and even neuroscience that shaming, blaming, and guilting someone shuts down the center of their brain responsible for learning and growth.

Here’s a question you can ask yourself as a litmus test prior to having a difficult conversation: Do I want to be heard or do I want to be effective? You must be brutally honest with yourself about your true intentions. If you use the tactics of shame, blame, and guilt, it blocks the ability of the person you are speaking with to actively listen and stunts the capacity for them to learn.

Calling forward, on the other hand, is a model of communication that we coined several years ago that flips the idea of “calling out” on its head, turning it into something more effective for bringing people together. While calling out is fighting against what someone did wrong, calling forward is an invitation to be something greater. While calling out is fighting against what we hate, calling forward is building upon what we love. Calling forward is inviting people into a greater state of integration and evolution.

To listen to the audio version read by co-authors Justin Michael Williams and Shelly Tygielski, download the Next Big Idea App today: