Kate Mangino has spent more than 20 years as a gender expert working with non-profits in the international development sector. She has worked with religious leaders in Malawi, women’s empowerment groups in Indonesia, and healthcare workers in Zambia—all with the end objective of addressing harmful gender norms.

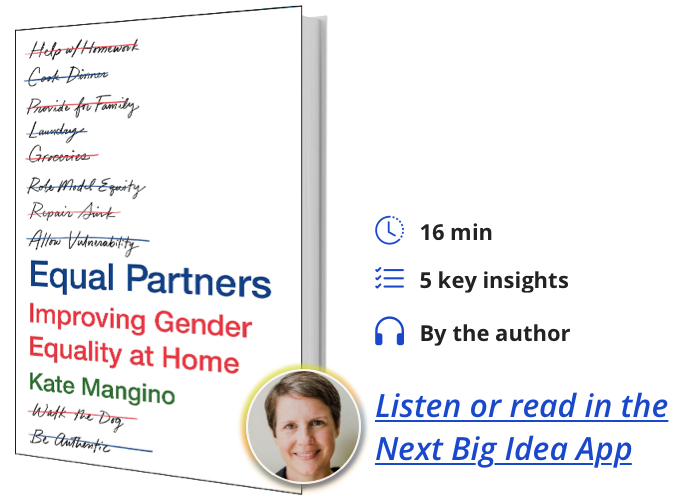

Below, Kate shares 5 key insights from her new book, Equal Partners: Improving Gender Equality at Home. Listen to the audio version—read by Kate herself—in the Next Big Idea App.

1. Stop blaming men, and stop fixing women.

Much has been written on this topic during the pandemic, when our individual household gender crises became a national emergency. When it comes to suggested solutions, I read a lot about fixing women (for example, how women can negotiate a more flexible schedule) and blaming men (for example, how male partners are not stepping up). The truth is that women don’t need fixing, and men are just as much victims of gendered culture as women.

To move toward equity, we need to avoid blaming the individual and focus our energy at the broader social system, acknowledging cultural behavioral conditioning based on gender identity. Nothing makes someone more defensive than an accusatory tone; the wall goes up, and the conversation stops. But when you say, “we’re all part of this system, and gender inequality hurts all of us,” then the possibility for a conversation is opened.

We’ve done a better job articulating how household inequality harms women. When women are over-burdened at home, it can greatly limit professional ambition and income potential, and lead to poor emotional health. In extreme cases, it can lead to depression and divorce.

But gender inequality also harms men. When men are forced to focus on work and are pushed away from family, they foster fewer emotional connections, and can feel isolated and alone. This leads to poor physical, mental, and sexual health.

Caregiving can be one of life’s most rewarding experiences. Caregiving triggers selflessness, empathy, and humility. It makes me sad that our culture discourages men from participating in these relationships. Girls are raised to value a clean and tidy home, which leads to women taking the brunt of the household work as an adult, which can force them to step back from professional opportunities. On the other hand, boys are raised to value professional ambition and income generation, which leads to men focusing on work as an adult, which can encourage them to step back from caregiving opportunities.

“To move toward equity, we need to avoid blaming the individual and focus our energy at the broader social system.”

2. Men’s glass ceiling.

Men today do much more in the home than their fathers and grandfathers before them, so we get fooled into thinking they’re doing an equal share of housework—but we have data that proves they’re not. This is partly because of gendered social norms. The bar is crazy low because we don’t actually think men can do more. We don’t think men are capable of doing more. But of course men can do more—a lot more. No one can convince me that a CEO or shift manager can’t apply their organizational and project management skills to the home. We just have to shift our social norms and expect it.

This is an issue I refer to as the “men’s glass ceiling.” This metaphor usually describes how women are held back professionally, but it is also an excellent description of how society protects men from household work by keeping our expectations low. If we don’t think men can do more, they probably won’t.

People of all genders need to think differently about men as partners and fathers. I want us to shatter that glass ceiling we’ve built above men’s heads, and truly believe that there is no limit to men’s capacity in the domestic space. Anything else is, ironically, patronizing.

3. Focus on aspirational masculinity instead of toxic masculinity.

We have collectively done a really good job of calling out men’s negative behavior. This is important, but should be balanced with highlighting men’s positive behavior. I identified 40 men who are living as equal partners in their home, meaning they do half of the physical and cognitive household labor. As shorthand, I call these positive deviants the “EP40.”

A lot of research in this area collects data from white, heterosexual, married, college-educated couples with kids. So, my EP40 is intentionally diverse. I oversampled men of color, included men without kids, men from a range of educational backgrounds, and men partnered with men as well as men partnered with women.

One of the most important findings from the EP40 is that none of these men believe they are giving anything up. They don’t feel bitter that they do more than their next-door neighbor. They don’t resent that they have less free time than their coworkers. They are equal partners because they want to be, and because they receive more in return than they give.

“We have collectively done a really good job of calling out men’s negative behavior. This is important, but should be balanced with highlighting men’s positive behavior.”

Let me tell you about Martin. Martin identifies as Latino and lives in South Texas. He was the third of six kids, and his abusive father left home when Martin was 12. At that point, being the oldest boy, he was told by relatives that he was now the man of the house. In reminiscing, Martin says, “How messed up is that? Telling a boy that age that he is the head of the house? As if a boy that age can take care of a home. But my mom helped me find my way. I couldn’t support my family financially, obviously. But my mom taught me how to do dishes and how to sweep and how to hand-wash clothes—what it took to run a home.”

Martin is now married to Evie, they have two young daughters, and Martin works in public transportation. Being an equal partner, to him, was the only choice. He knew what it took to make a home run, and he knew it was unfair to expect one person to do all the work. He provides for his family by earning a wage and by doing half of the physical and cognitive labor in his household. He told me, “Being with Evie and the kids, I am living my best life. I get so much joy from being a partner and a father. Sure, not every day is a great day. But I always love her. We can always talk about stuff. And then maybe the next day is better.”

4. Recognize the invisible load carried by dads of color.

In her book Fair Play, Eve Rodsky talks about the importance of naming the invisible load typically associated with women’s work. It is also important that we name the invisible load carried by dads of color. Let me explain with Will’s story.

Will is a Polynesian-American born and raised on the West Coast. There was no room for mistakes as one of the few Brown children in a white suburb. As a child, he was very conscious of how he was perceived in public, and this stayed with him as an adult. Will is now grown, married, and father to three children. One of his children is a person with autism who is prone to public outbursts. The child presents white, while Will’s own skin is dark.

Will explains, “It happens a lot that I am out with my son—he gets angry, and I have to physically restrain and remove him from a particular situation. Every time I think it is just a matter of time before someone calls the police. It goes back to when I was a kid—no matter how good of a dad I am being, people assume the worst in me.”

“We need to push ourselves to consider our unseen privilege and acknowledge that dads of color carry an invisible load.”

In our initial interview, this story just about knocked the wind out of me. My little brother is a person with disabilities, and I remember many times when my mom and dad had to parent him in public spaces. There were stares and misunderstanding, and I wonder how much harder it would have been if we were not white. We need to push ourselves to consider our unseen privilege and acknowledge that dads of color carry an invisible load. If it is hard for white dads to care for their kids in public, or tell their work that they need time off to be a parent, it is harder for dads of color, dads with a disability, immigrant dads, or dads of any minority group.

To counter the disproportionate pressure on dads of color, we need to be as enthusiastic to rewrite norms around race as we are to rewrite norms about gender.

5. Household gender inequality is a community responsibility.

Most published writing about household balance is aimed at women, or at least parents. Pieces turn up in parenting blogs or the family section of the bookstore. But this is an intergenerational problem that is much bigger than any individual or family. This is everyone’s responsibility—from Gen Z to Baby Boomers. If you are a grandparent, aunt, uncle, friend, neighbor, faith leader, community member, single or committed, or a supervisor or executive—we need you. Decisions are often made within the nuclear family, but we exist in communities, extended families, and workplaces. The messages we receive from those groups make a big difference.

Listen to Matthew’s story, for example. Matthew identifies as white and is from New England. His father was the groundskeeper for a small private school, and his mother was a nurse. He grew up with three siblings, and describes his childhood home as friendly and loving. Matthew grew up to marry Janie, who is a physician. Her job requires long hours. When their kids were little, Matthew and Janie felt stressed. Janie earned enough income for the family, so they decided that Matthew would be a stay-at-home dad for a while. The situation worked well for the nuclear family, but not for the extended family. When his sister-in-law chose to leave work several years earlier, the family congratulated her on putting the kids first. But when he left work, he only heard snide comments suggesting he was lazy and not pulling his weight. Matthew went back to work fairly quickly. He found a job that was flexible so he could remain the “alpha parent,” but he looks back on that time with regret.

Matthew isn’t unique. Probably tens of thousands of men have wanted to take parental leave at the birth of a child, but didn’t because they feared negative retribution at work. We all need to embrace that providing for your family—by any gender—is not just about earning income.

To listen to the audio version read by author Kate Mangino, download the Next Big Idea App today: