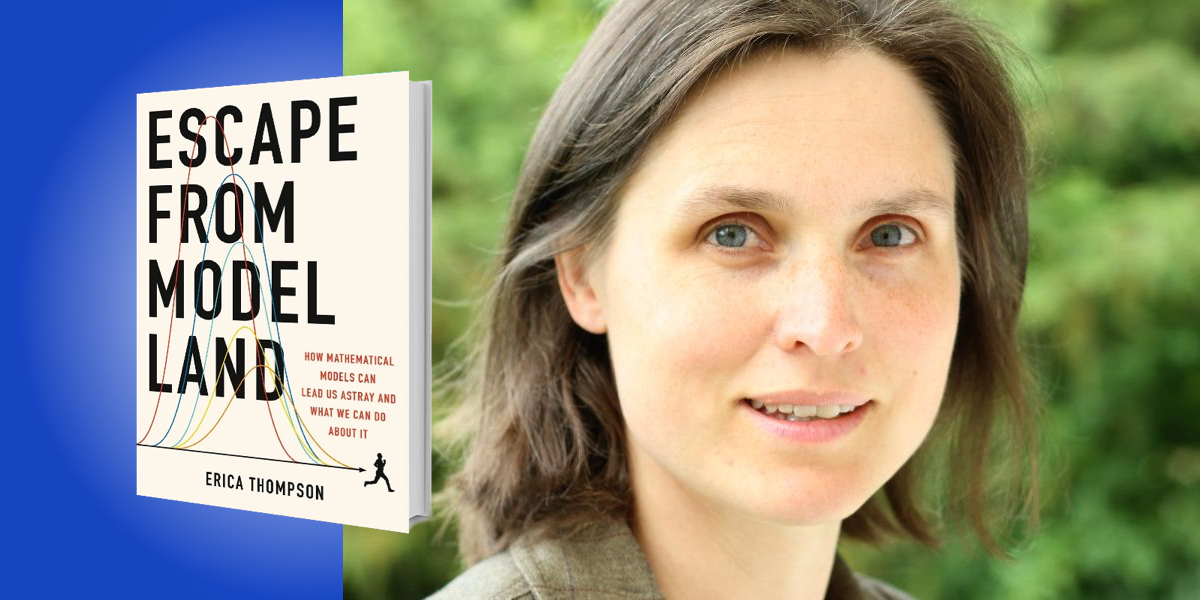

Erica Thompson is a Senior Policy Fellow at the LSE Data Science Institute, where she studies the use and implications of mathematical models in science and society. She gained a PhD in Physics from Imperial College London on statistical and dynamical modelling of North Atlantic storms under climate change.

Below, Erica shares 5 key insights from her new book, Escape from Model Land: How Mathematical Models Can Lead Us Astray and What We Can Do About It. Listen to the audio version—read by Erica herself—in the Next Big Idea App.

1. Models shape our world.

From spreadsheets to supercomputers, mathematical models are ubiquitous. Not just in science, but also in business strategy, banking, commercial operations, and government. In fact, they form an invisible foundation for much of daily life. Models inform interest rates, investment decisions, climate and energy policy, public services, new technologies—you name it.

Models can help us harness the laws of physics. Models of gravity have helped us land space missions on other planets. Models of the climate help us understand what might happen if we continue burning fossil fuels, and models of the economy help us to understand what might happen if we make market interventions to reduce carbon emissions. More recently, models of viral transmission have been central to decision-making about the COVID-19 pandemic.

2. Models change the way we think.

If you heard the words “flatten the curve” in spring 2020, you were listening to a model. That simple model helped communicate the urgency of the situation to hundreds of millions of people. More complex models offered options to policymakers. Should we ask people to stay home? Should we close schools and workplaces? What will be the impact on health services? These models helped navigate a difficult, highly uncertain, rapidly evolving situation.

“The kind of model that we turn to changes the way we think about options and appropriate action.”

Similarly, climate change can be presented as a one-dimensional question of reducing carbon emissions, or as a one-dimensional question of supporting individual freedoms. Or we can try addressing more of the complexities and trade-offs that are involved in constructing a social and political response to the multiple challenges of the 21st century. Again, we have a difficult, highly uncertain, evolving situation, and different needs and values to balance. The kind of model that we turn to changes the way we think about options and appropriate action.

3. Models contain values and politics.

You might think that there isn’t any politics in mathematics. Well, that’s not true. Think about the epidemiological models that informed lockdowns in early 2020. They were useful, but didn’t tell the whole story. One side of the pandemic story is the physical health of the population, and the impact on already-stretched health services. Another side of the pandemic story is the economic impact of the disease burden on labor forces due to deaths, incapacity, and long-term illness. Another side is the economic impact was the lockdowns themselves: the struggle of small businesses to survive, and the huge financial actions taken by governments. Other aspects include mental health, swings in property values, and changing attitudes towards work.

These are all important parts of the pandemic story. Models can represent some aspects, but I don’t know of any model that tries representing all these things. It would be too unwieldy to construct and too difficult to interrogate for simple advice. To make a model at all, we have to simplify. In doing so, we make value judgments about which aspects are most fundamental or most relevant to the decisions we want to make. These judgments, even when we write them in mathematical language, are inherently political.

4. Models don’t just predict the future.

Like pandemic models, other models predict the future, but not perfectly. We see through a glass darkly. Climate models, business models, energy system models, asset valuation models, models of inflation or interest rates, models predicting who might win the next election—none of these can be 100 percent confident of having the right answer, and would not be particularly useful if they did. We make these models not for predicting the future, but to inform decisions aimed at creating the future we want—ensuring a stable climate, keeping the lights on, making good investment decisions, or swaying an election. Models are part of the conversation and process of understanding the world and deciding how to act in order to change the world.

“We make these models not for predicting the future, but to inform decisions aimed at creating the future we want.”

One example is the integrated assessment models of energy and climate that help decide how to meet climate-change targets in achievable and cost-effective manners. The models contain cost estimates for fossil fuels, renewables, nuclear power, and so on, and find the lowest-cost way of getting to 2100. But the decision about what these costs should be is dependent on political and social outcomes. Will technologies develop fast or slow? Will they be subsidized or taxed? Will citizens choose to change their behavior spontaneously or in response to price signals? These models make political judgments about what is feasible, and in doing so, they change the kind of world that we are going to live in.

Currently, the models assume that carbon dioxide removal technologies will be successful and cheap, that the cost of behavior change is very high, and, for example, that geoengineering technologies are not politically feasible. But it would only take a tweak in one parameter to change each of these judgements, and changing that one parameter in one abstract mathematical model could have enormous consequences for the world.

5. Models have power.

Whether you like it or not, mathematical models are changing the way we think and act as individuals and as a society. They contain value judgments and political opinions. And models are more accessible than ever: from apps on your smartphone to the most advanced artificial intelligence tools. We need a conversation about modeling that can demystify assumptions and allows everyone to participate in discussion about value judgements—not only those with advanced mathematics degrees.

To listen to the audio version read by author Erica Thompson, download the Next Big Idea App today: