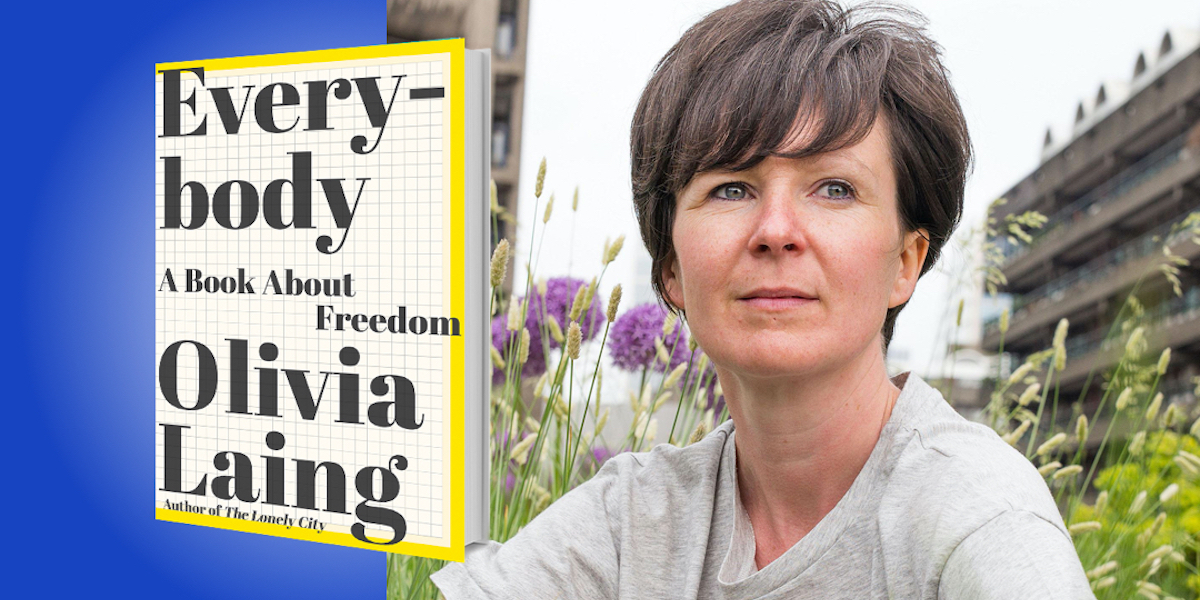

Olivia Laing is the author of three acclaimed works of nonfiction, including The Lonely City (2016), which was nominated for the National Book Critics Circle Award in Criticism and has been translated into seventeen languages. Her first novel, Crudo, was a New York Times Notable Book and won the 2019 James Tait Black Prize. She writes for the Guardian, New York Times, and frieze, among many other publications.

Below, Olivia shares 5 key insights from her new book, Everybody: A Book About Freedom (available now from Amazon). Listen to the audio version—read by Olivia herself—in the Next Big Idea App.

1. Our difficult bodies.

It isn’t easy to inhabit a human body. As we’ve all seen over the past year of protest and plague, the body is vulnerable to violence and illness. A body is a solid form, but it’s also frighteningly open and porous.

In 1920s Vienna, a young psychoanalyst came up with a startling idea about what our bodies mean. Wilhelm Reich was Freud’s most brilliant protégé, but he broke with the master’s model when he began to suspect his patients were carrying the difficulties of their past around in their bodies, storing the undigested emotions as a kind of tension he compared to armor.

“While our bodies might be vulnerable, they are also a source of astonishing power.”

Reich believed our bodies are the storehouse for trauma, and what’s more, he didn’t think that this trauma was entirely emotional in origin. His patients were predominantly working class, and it was plain to him that their distress was caused by factors like poverty, overwork, and poor housing—which could never be addressed by psychoanalysis alone. By the end of the decade, he’d become convinced that the only path to freedom was to change the social system, and that the way to do it was to liberate people’s bodies.

2. The power of protest.

Reich had a radical vision. He understood that while our bodies might be vulnerable, they are also a source of astonishing power. As fascism began to creep across Europe, he transferred operations to Berlin, where he worked as a psychoanalyst, sexual liberationist, and anti-fascist activist.

He believed that sex was a way to process the pain of the past and to experience true bodily freedom, and so he worked to sweep away some of the shame and prohibition that continues to cling to our sexual lives. As an anti-fascist activist, he also thought that bodies on the streets could change the world. This faith in the power of protest is borne out by all the great liberation movements of the twentieth century, whether it be sexual liberation or gay rights, feminism or the civil rights movement. From the Stonewall riots to the march from Selma to Montgomery, resistant bodies have changed laws and reshaped history.

I’m talking here from personal experience. I grew up in a gay family during a markedly homophobic era in Britain. When I was eleven, I went on my first protest march. It was the height of the AIDS crisis, and marching across London with those angry, joyous, resistant bodies left an indelible mark on me. For the first time I saw the power of solidarity, an unstoppable force.

“From the Stonewall riots to the march from Selma to Montgomery, resistant bodies have changed laws and reshaped history.”

3. We are all in a grid.

The problem with being a body in the world is that you aren’t just an individual. To be born at all is to be situated in a network of relations with other people, and furthermore to find oneself forcibly inserted into linguistic categories that might seem natural and inevitable, but are actually socially constructed and rigorously policed—whether these are to do with race, gender, sexuality, or ability.

We’re all stuck in our bodies, stuck inside a grid of conflicting ideas about what those bodies mean, what they’re capable of, and what they’re allowed or forbidden to do. Not all bodies are shot by the police; not all bodies are subject to rape and harassment on a daily basis. Expectations, demands, prohibitions, and punishments vary enormously according to the kind of body we find ourselves inhabiting. The realization that embodiment is more dangerous or oppressive for some people than others is what drove the freedom movements of the past, and continues to inform the struggles of today, from Black Lives Matter to MeToo.

4. What freedom means.

Freedom is not as straightforward a concept as it sometimes seems. There are two kinds of freedom, I think. The first is about doing whatever you want, without acknowledging the needs or vulnerabilities of other people. This is the freedom of the person who refuses to wear a mask because it inconveniences them, never mind that it might jeopardize their neighbors; this is the freedom of the baker to refuse to make a wedding cake for a gay couple.

“You don’t have to secure a permanent victory; all that is required is that you show up and contribute.”

The other model of freedom is different. It’s about finding ways to live without being hobbled, damaged, or actively destroyed because of the kind of body you were born into. It’s about dismantling an unequal grid of rules and laws that many people refuse to acknowledge, even as it visibly destroys their neighbors.

As we grapple with the malignant forces of misogyny and white supremacy, it’s crucial we remember that freedom is not a zero-sum game, or a possession you can hoard. As the British novelist Angela Carter once said, “My freedom makes you more unfree if it does not acknowledge your freedom also.”

5. The long game.

When I started writing Everybody in 2015, I was filled with despair. The far-right were on the rise again just as they had been in Reich’s era, and his vision of freedom was far from being achieved. There was no republic of unencumbered bodies, unharried by any hierarchy of form. Furthermore, it was beginning to seem as if the victories of the great liberation struggles were being reversed, assuming they’d been achieved at all.

I’d spent my twenties as an environmental activist, and I was increasingly worried that this kind of activism was pointless. But what I learned from looking back at the movements of the past century is that liberation struggles have never proceeded unilaterally. That sounds dismaying, but what it really necessitates is a shift in mindset. Freedom is a shared endeavor—a collaboration built by many hands over many centuries of time, a labor that every single living person can choose to hinder or advance. You don’t have to secure a permanent victory; all that is required is that you show up and contribute. There’s no need to give way to despair; all that is required is to play a part.

To listen to the audio version read by Olivia Laing, download the Next Big Idea App today: