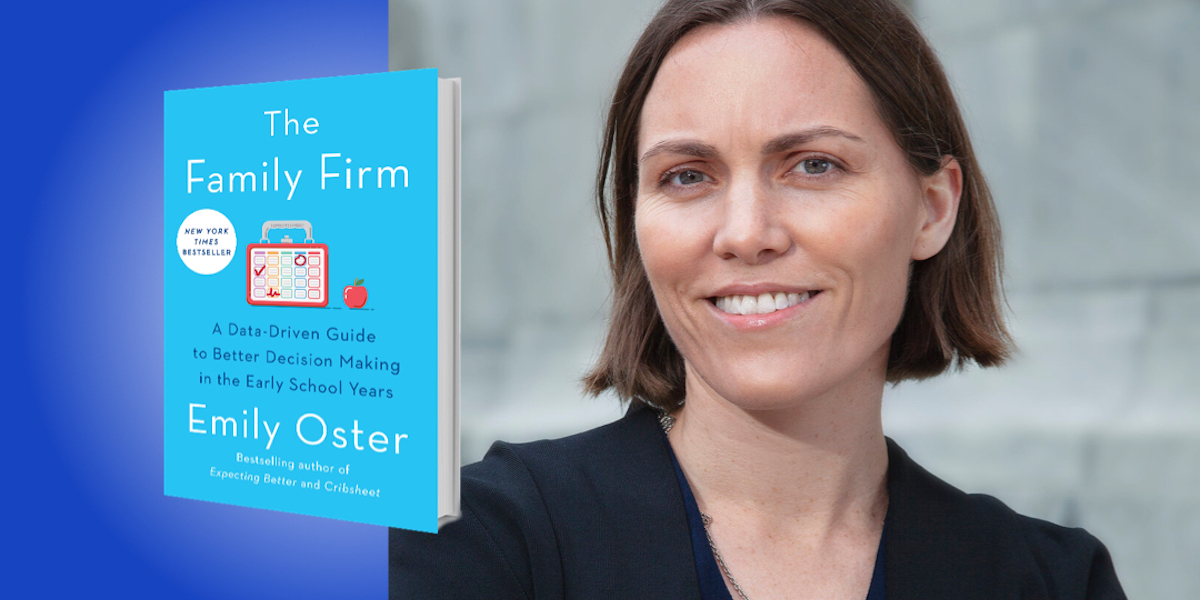

Emily Oster is a professor of economics at Brown University and the author of three books: Expecting Better, Cribsheet, and The Family Firm. She also writes the Substack newsletter Parentdata.

Below, Emily shares 5 key insights from her new book, The Family Firm: A Data-Driven Guide to Better Decision Making in the Early School Years. Listen to the audio version—read by Emily herself—in the Next Big Idea App.

1. Better business practices can help families.

Well-run firms have a business plan, and they make decisions deliberately with an eye toward the company mission. They also have processes to make things run smoothly, so not everything lives in the head of one person.

Just like your business, your family probably has a mission, even if it’s an unstated one. But most of us don’t refer to that mission when making family decisions, and you probably don’t embrace the same kinds of business processes that you do at work. We often shy away from thinking about our family like a firm because it seems unemotional and cold. But if we can get past that, we can make the logistics of our lives run better, and we can leave more time for fun.

Let me give you an example. In my household, sometimes we’ll have a conversation about family logistics, and then afterwards my husband will send me an email with bullet points, listing the things that we agreed on and the next steps. Even though it seems a little clinical and unusual in the moment, it means that we don’t have to talk about those logistical things when we’d like to be having a fun conversation. We are using more efficient, better business processes to get through those logistical hurdles that always come when you’re a busy parent of busy kids. The message here is basically, “I love you a whole lot. And I still want you to update the household Asana tasks.”

“We can make the logistics of our lives run better, and we can leave more time for fun.”

2. Create a big picture.

When planning out your family life, you should sit down with a calendar and think a little bit about what you want your day to look like. What pieces do you want to make sure are there? If you have decided, as my family has, that sitting down for dinner every night as a family is a very important part of your day, then there are a lot of things that you’re not going to be able to do. In my case, my kids don’t participate in a lot of extracurriculars, because many of them would interfere with our family dinner, this central activity that we have decided is important. On the other hand, if extracurricular activities like sports are very important to you, then you may not want to schedule a family dinner as a consistent calendar item.

There’s nothing inherently good or bad about either of these systems. They are both ways that you may want to run your family. But by creating this kind of big-picture, overall image of what your life would look like ideally, or at least what it would look like realistically under the constraints that you face, it’s going to help you make a lot of decisions later on.

3. Use the four F’s.

Big decisions—like what school should my child go to?—don’t come up every day, but when they do, they can be challenging. They can take up a huge amount of our mental space, and it can be hard to be confident that we’ve made the right choice.

“Just because you’re moving on from your decision doesn’t mean you can never revisit it.”

I advocate using a very formal, structured process to handle big decisions: The Four F’s.

- Frame the question: The first step is to say: What am I asking? What is the real question? What is the framing of the question that makes sense? If I’m making a school choice, I’m not choosing between an infinite set of schools; I’m probably choosing between one, two, or maybe three options. It may even be that in fact, there really isn’t any choice, and I’m just obsessing about this decision, even though there is no decision to make.

- Fact find: Gather data, maybe some information about the schools, how kids perform when they finish the schools, or what kinds of kids are in the schools. But also get all the information you need about logistics and the impacts this decision will have on the other parts of your family life. This takes time and effort, but eventually you will get to a moment where you feel you have all the information that you need.

- Final decision: You can’t just endlessly gather information and think about it all the time. You need to schedule a time for making a decision and moving on.

- Follow up: Just because you’re moving on from your decision doesn’t mean you can never revisit it. In fact, we should plan to revisit almost all of our big decisions at some point, particularly at times when a change would be appropriate.

4. Don’t micromanage; transfer responsibility.

Imagine that it’s normally part of your job to order sandwiches for the Thursday office lunch, but you’re really busy this week so you ask a colleague to place the order for you. Would you stand over them while they were ordering and say things like, “No, no, not so much turkey,” or “No, people like cookies, but not peanut butter cookies”? You would never do that at work because it would be counterproductive and disrespectful.

“If we can get on the same page about the general rules, then anybody can implement them, and we do not need to micromanage.”

But we often do that kind of micromanaging at home. Think about a parallel situation where normally one parent is responsible for getting the kid ready for camp, and on a particular day, another parent has taken over that job. It’s not so hard to imagine the first parent chiming in with comments like, “No, you’re not doing it right. That’s not the sunscreen we use. That’s not the right kind of snack.” But just like at the office, that kind of behavior is disrespectful. It’s also not productive, because presumably you asked the other person to do this because you had something else to do.

Unlike at work, at home we are reluctant to do what I call total responsibility transfer, where you transfer the entire responsibility for an activity onto somebody else. If we can get on the same page about the general rules—people have to wear sunscreen every day, snacks should be something healthy, etc.—then anybody can implement them, and we do not need to micromanage. If you are the micromanager (which is me in my household), you have to try very hard not to micromanage if you have in fact transferred responsibility.

5. Sleep is important.

Kids need sleep. If you are a parent, you will know this because you’ve probably experienced times when your child did not sleep well and then acted like a jerk. But there’s also a lot of data to support it. In randomized trials, kids who were put to bed one hour later than usual for four days in a row performed worse on a series of memory and cognitive tasks.

But the necessary amount of sleep can vary a lot for different children. Between 9 and 11 hours is typically recommended, but some kids really need 12 hours, and others do just fine with 8. So how do you know if your kid is getting enough sleep? Observe their behavior. If they show signs of sleepiness during the day, they’re not getting enough sleep at night. If you let them sleep in on the weekends, and they sleep two or three more hours than they would otherwise, then they’re also not getting enough sleep.

Prioritizing your child’s sleep may mean altering some things that you or your child want to do, but in the big picture, it will pay off.

To listen to the audio version read by Emily Oster, download the Next Big Idea App today: