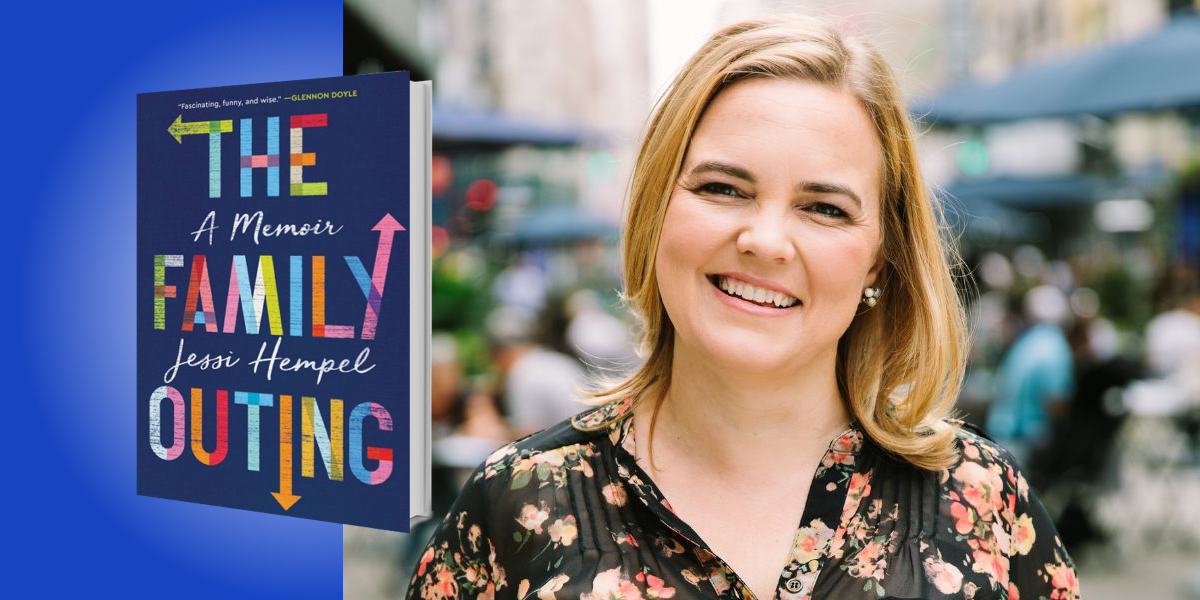

Jessi Hempel is host of the award-winning podcast Hello Monday, and a senior editor-at-large at LinkedIn. For nearly two decades, she has been writing and editing features and cover stories for magazines including Wired, Fortune and TIME about work, life and meaning in the contemporary age. She has appeared on CNN, PBS, MSNBC, Fox, and CNBC, addressing the culture and business of technology. Hempel is a graduate of Brown University and received a master’s in journalism from UC Berkeley.

Below, Jessi shares 5 key insights from her new book, The Family Outing: A Memoir. Listen to the audio version—read by Jessi herself—in the Next Big Idea App.

1. Memory is unreliable.

Even when all five members of my family tried in earnest to remember the events of our family life and align on our stories, nothing matched. That’s because we each encode memories differently, and those memories have changed in the telling and retelling. So, when we can’t agree on what happened, it doesn’t necessarily mean anyone is wrong.

For example, nearly three years after my parents’ marriage first came apart, they still hadn’t divorced. My siblings and I remember scheduling a conference call to tell them we felt they should get the paperwork done, fully separate their lives, and move on. Evan remembers the empty college dorm room he was sitting in during his school break. Katje remembers taking the call from the bedroom of my house. I can even sort of hear the surprise in my Dad’s voice when he picks up and discovers all three of his kids are on the line. As we remember it, we told them we thought they should get a divorce already and move on.

But neither of my parents has any memory of this call. Upon reflecting, this makes sense to me: our parents’ marriage was never about us. It was about them. So our opinions about when it should end weren’t as central to them as their own opinions.

“It was only when I let go of needing to be certain about the factual truth that I became open to a deeper, more collective experience.”

Throughout my reporting, peoples’ memories clashed. Mom remembered a dinner in 1989 that Dad was certain happened in 1982 and that I couldn’t place at all. It was only when I let go of needing to be certain about the factual truth that I became open to a deeper, more collective experience. When I really listened to everyone, an emotional truth emerged. Although there are some things in this book that not everyone remembers, everyone agrees that this story represents the emotional truth—and we’re now clear that that is more important.

2. When someone tells you who they are, listen.

Often when the people with whom we are closest—family members, for example, or close friends—share new information with us, we feel threatened. It causes us to question our own identity, to ask ourselves how we missed something so fundamental about a person we love. It’s important to exercise some self-compassion here. This is normal! We are human! But we can strive to show up differently.

Consider the phone call my brother made to tell me he was trans. I had been out of the closet for half a decade by then. I considered myself to be a progressive person, and had friends who were transgender. But when Evan told me that he was a boy, I didn’t let him finish his sentence before I dismissed what he was telling me. “I just saw you over the holidays, and you were wearing that long, flowy dress,” I told him.

Looking back, I regret this. I wish I had made more space to listen to him in those moments, to hear what he was trying to tell me. Now, when someone reveals something to me and I don’t know what to say, I aspire to embrace three words: tell me more. When I don’t know what to say, I just keep listening.

3. Center other peoples’ experiences.

Nearly half of the story in my book occurs before my brother comes out as transgender. He is a character, and sometimes even the central character. Yet during this time in our lives, my own memory casts him as a little girl. Thinking back, I remember that the idea of being the oldest of three daughters was central to my identity. It defined how I thought about myself. I wondered: how could I write about this honestly? What did that even mean?

“New truths open up when I center other people’s experiences, when I attempt to imagine life as they experience it.”

I perceived this to be a conundrum, and I tried to ask my brother to solve it. I didn’t plan to use his dead name, which is the name he was given at birth and chose to give up when he came out. I didn’t want to refer to him wrongly. But how was I supposed to navigate the moments when my memory conflicted with his experience?

My brother didn’t see this as a problem. “I’m Evan,” he told me. “Write about me as Evan.”

“You mean, as a boy?” I asked. He had every right to be frustrated with me when I asked this question. Instead, he was gentle with me.

“Yes, write about me as who I am, who I’m telling you I always was.”

So, I tried it. I began to center my brother’s experience. I wrote about the child Evan was, the creative and stubborn and persistent first grader who grew into a withdrawn and pragmatic adolescent. As I wrote about my brother with the pronouns he chose, centering the experiences he identified as important, an unexpected thing began to happen for me: I began to see him more clearly for who he was. I began to understand him differently, and also to know him better.

My takeaway: I’ve spent a lifetime centering my own experiences in life, exploring my own perspectives. But new truths open up when I center other people’s experiences, when I attempt to imagine life as they experience it.

4. Show up.

My father’s first husband, Ron, was a beating heart inside a bear of a body. Everyone loved him because he was so good at loving everyone. He’d been diagnosed with HIV in 1987, when it was a death sentence, but he’d survived. He eventually succumbed to cancer in 2009, but his life felt like a miracle. He never lost sight of the preciousness of each day.

Not long after Dad and Ron married, my mom’s sister died unexpectedly. I was around 30. My siblings and I had had a difficult relationship with my mom’s sister, and neither of them planned to fly out to Illinois for her funeral. I wasn’t really sure what to do. I didn’t have much vacation at my magazine job, and my paycheck wasn’t huge. The plane ticket would cost $520, about half of my savings at the time. I explained all of this to Ron and Dad. “What should I do?” I asked them.

“Oh there’s no question here,” Ron replied. “You sit next to your mom at her sister’s funeral.”

The response was so simple, and the sentiment was clear: show up. I paid $520 for the ticket, and I have never missed that money, nor do I remember what assignment I might have been working on at the magazine. I have never regretted sitting next to my mom at her sister’s funeral.

When it comes to the people who are closest to us, we rarely regret showing up.

5. Put your own life jacket on first.

Earlier I mentioned a conference call in which my siblings and I call our parents to ask them to divorce. At least, that’s how I remember it at first.

“When people we love go through hard times, we often want to make things better for them.”

While I was working on the book, I stumbled across an academic book I’d forgotten about. It’s called Families like Mine: Children of Gay Parents Tell it Like it Is. It was published in 2004, just a couple years after the conference call. The author, Abigail Garner, interviews both me and Katje for this book. I tell her about the conference call. I’m 27 at the time, recalling something from just a few years earlier. And here’s my quote, just as it’s published: “We called them on a conference call. We told them, ‘We are your children and we need to make a few things clear. We can’t take on your burdens. We need to know you are okay. We think you should divorce, and we know it will be on your time. We don’t want to know the axis of your crisis; we just need to know you’re okay. We want to know you have good therapists. But we really can’t deal.”

This small piece of my personal history preserved is a gift.

When people we love go through hard times, we often want to make things better for them. We usually can’t. This is even more true when those people are our parents, our children, our siblings. Often the only thing we can do is love them enough to maintain our own boundaries so that when they emerge, we aren’t so angry at them and broken by them that we cannot be in a relationship with them.

In this passage, I can see what I didn’t remember, that our call was not in fact to tell our parents to divorce. It was to tell them how to treat us, where we belong in their lives, what roles we are willing to play. It doesn’t matter now that they cannot remember it. It doesn’t even matter that we cannot. At that vulnerable moment in our family’s history, Katje, Evan, and I took care of ourselves instinctively. This is a way that we took care of them.

To listen to the audio version read by author Jessi Hempel, download the Next Big Idea App today: