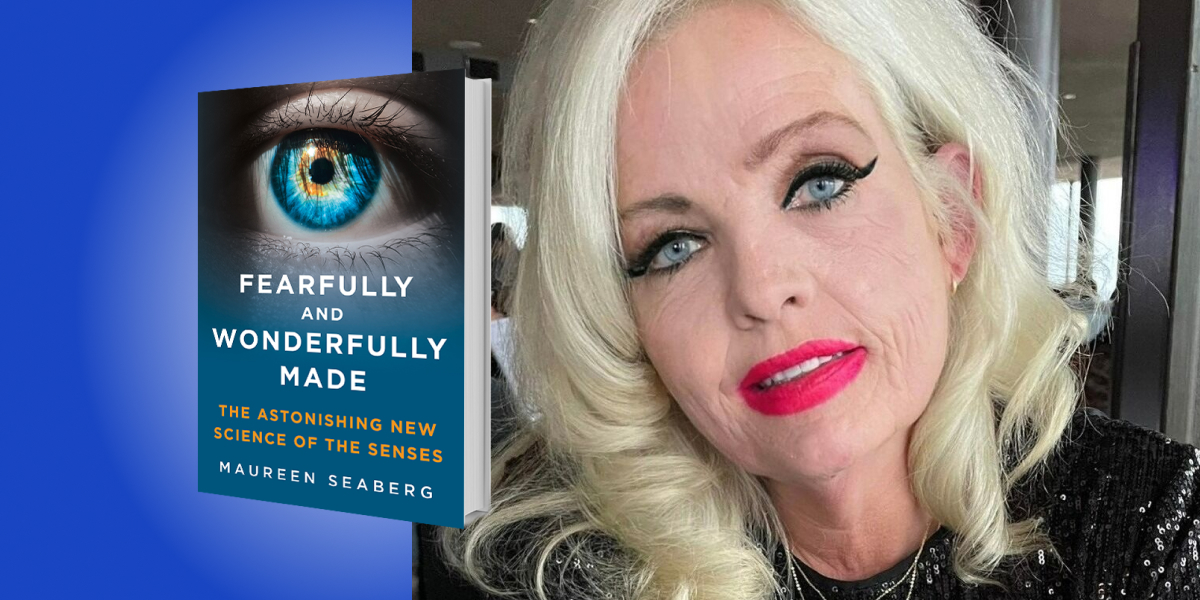

Maureen Seaberg is a writer, speaker, and sensory research subject who has been laboratory-proven to be a super color seer, or tetrachromat—meaning she has a fourth cone class for color vision. She worked as a consultant for MAC Cosmetics on their hugely successful “Liptensity” lipstick line. Her work has been published in publications such as the New York Times, National Geographic, Vogue, Glamour, and ESPN Magazine, and she has appeared on NPR, CNN, and PBS, among other networks. She has also presented about the senses at institutions such as Vanderbilt University and Yale Divinity School.

Below, Maureen shares 5 key insights from her new book, Fearfully and Wonderfully Made: The Astonishing New Science of the Senses. Listen to the audio version—read by Maureen herself—in the Next Big Idea App.

1. Sensory research is a frontier for human development.

Perceptual laboratories are in a golden research era—they are awash in funding for AI, robotics, virtual, mixed, and augmented reality. But as scientists try to achieve “sentience” in these artificial realms and match human experience, they are discovering that humans are more powerful than we realized.

We can see light at the level of a single photon, hear sounds with amplitudes smaller than an atom, smell a trillion scents, feel a single molecule change in thickness on a smooth surface with our bare fingertips, and we have discovered a set of taste buds for discerning fresh water.

Even as the world becomes more advanced, we are the finest technology on the planet. We are “soft-tissue/high-technology,” according to anthropologist William C. Bushell. No machine can match us and we reign supreme over the rest of the animal kingdom. It’s like finding out the oil painting that your grandmother willed to you is an old master, only you are the painting. You are much finer than you know.

2. Our senses can be shaped, practiced, and heightened.

I interviewed a retired Scottish nurse and grandmother named Joy Milne. She’s a super smeller.

Joy detected a change in her husband’s body odor six years before he developed Parkinson’s disease and has since helped scientists isolate the molecules she had smelled to create swab tests for diagnosis. Thanks to her, doctors can discover Parkinson’s as many as ten years earlier than before and provide better initial care. She is now detecting COVID, cancer, and tuberculosis this way with researchers. Mrs. Milne teaches us to smell everything at least twice—at various stages of an aroma’s unfolding—to become a better sensor.

“Within weeks of exposure, he too smelled the chemicals.”

Sensing is also about exposure. I wrote of a Monell Center scientist who volunteered to prepare an unpleasant solution in his laboratory because he was part of the half of humanity who cannot smell it. Within weeks of exposure, he too smelled the chemicals.

In my case, scientists say that if I did not have a large vocabulary for color, my tetrachromacy genes may not have become functional. So, by paying attention, having exposure, and creating language pathways for sensory things, you can widen your senses.

3. Sensory abilities should be considered a form of intelligence.

Given how powerful the senses are, it is possible that a new index, which I have named PQ (the perception quotient), is even more important to survival than IQ (intelligence quotient) or EQ (emotional quotient).

In 1884, when Sir Francis Galton created the first test for intelligence, he examined his subjects’ senses. He checked vision, hearing, and reaction times to various stimuli. A few years later, in 1890, James McKeen Cattell pioneered the first standardized mental test. He also measured the speed and accuracy of people’s sensory perceptions. Measures of sensory perceptions fell out of favor because they could not predict academic achievement. I believe the world needs something more primal and animalistic in this fragile age.

PQ puts us in better touch with all our faculties. Unlike traditional intelligence, it can be learned and grown.

4. You are already sensing things that do not rise to conscious awareness.

Painter and mother of four, Carrie Barcomb, came to realize her own super abilities after a friend told her about Joy Milne’s extraordinary nose. Looking back, Carrie realized it had been there all along—the sour smell of her children’s breath when they had stomach viruses, the burning taste in her own mouth when she was getting a cavity, the unique funk of her pet dog when it came down with a flea allergy.

“There are many super sensors in the world waiting to be discovered.”

Please think of me as the friend who validates you and tells you these things are possible. I know there are many super sensors in the world waiting to be discovered. I was not proven to be a tetrachromat until recently, in middle age. We live at the dawn of a new sensory climate and awareness, and I hope you recognize yourselves in my work.

5. The path to vivifying your senses.

I have distilled the wisdom of the latest sensory research and interviews with super sensors into a ten-step model to help you vivify your senses. Using the handy acronym PERCEPTION, I walk readers through simple and enjoyable steps.

In addition to the practice, exposure, and vocabulary steps I noted earlier, one of the easiest and most enjoyable methods for sharpening perception is the “N” of my acronym—nature. North Americans and Europeans are spending an astounding 90 percent of their lives indoors, which dulls the senses and may be why we have been so wanton with the environment.

Scientists found that Malaysian hunter-gatherers who live off the land have a far more evolved sense of smell than more settled people. They were also able to identify more colors when tested. The benefits of being outdoors should inspire us to do as much in nature as possible.

To listen to the audio version read by author Maureen Seaberg, download the Next Big Idea App today: