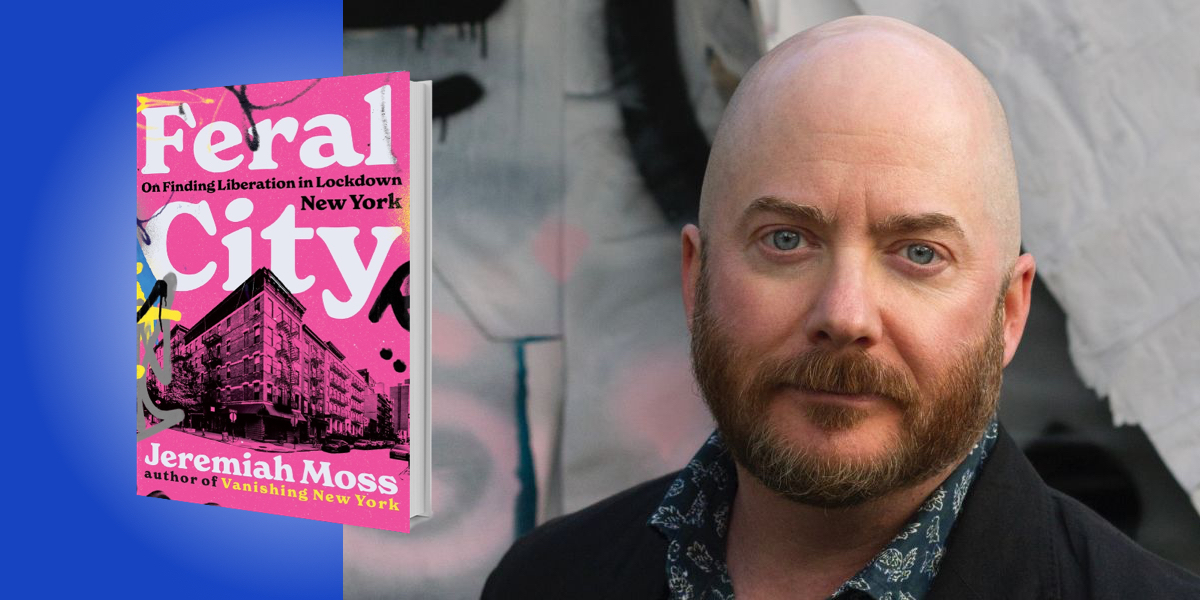

Jeremiah Moss writes about city life on his blog, Feral City, and his work has appeared in many publications, including the New York Times, The New Yorker, Paris Review, and n+1. He is also a psychoanalyst in private practice in New York City.

Below, Jeremiah shares 5 key insights from his new book, Feral City: On Finding Liberation in Lockdown New York. Listen to the audio version—read by Jeremiah himself—in the Next Big Idea App.

1. Emptiness gives permission.

When New York City went into lockdown at the start of the pandemic in March 2020, the streets and public spaces emptied of people. Tourists disappeared, people stayed indoors or moved away, and many middle-class and wealthy New Yorkers fled to their weekend homes in the country.

In this emptiness, a psychic shift occurred. Those of us who remained behind suddenly felt free to take up space in different ways. I saw people dancing spontaneously in the streets, flapping their arms while they walked, and singing songs on the sidewalks. It was as if people had started to unfold and expand. I felt freer too, less controlled, and this made me curious.

What was it about that emptiness—specifically, the emptiness of a city during a plague—that led to such profound disinhibition? Did the ever-presence of ambient death loosen our behavior? Was it a feeling of human connectedness in a time of collective trauma? How did the absence of a particular social class (the hyper-normals) affect behavior? I began to get the idea that all these factors played a role.

2. Hyper-normativity is a police force.

Many of the more recent newcomers to New York City conform to a hyper-normal way of living and publicly presenting themselves. They are what some social theorists call ideal neoliberal subjects, people who fiercely adhere to the values and aesthetics of late-stage capitalism. Treating themselves—and the world around them—as consumer products and personal brands, they are what psychoanalyst Christopher Bollas called abnormally normal.

Bollas wrote about a personality type that developed in the 2000s, after neoliberal capitalism. He called it the normopathic personality and this mindset became pervasive through globalization. This type of person de-subjectifies themselves, removing from themselves all traces of individual personality. It’s a dehumanizing process which protects oneself by blending into the crowd.

“This type of person de-subjectifies themselves, removing from themselves all traces of individual personality.”

Because humans are a social species, we tend to bend to the norms of the majority. When the hyper-normals take up most of the space in a community, like an urban neighborhood or a public park, they quietly dictate how everyone present should look and behave. In this way, they radiate a covert social control. Consciously or not, they are a police force. When they left the city in 2020, that control went with them, and New York became looser and freer in their absence. It felt more like the old New York that I remembered from the 20th century.

3. New York City changed after 9/11.

Until the 2000s, New York—like other countercultural cities—was a place of liberation. Historically, it was a safer place to be if you were outside the established American norm of straight, white, and Protestant. But New York changed after the terrorist attacks of September 11, 2001, when politicians and business leaders reoriented the city around American patriotism, policing, and capitalism.

People who never would have lived in New York before flooded into the city. They didn’t like the dirt, chaos, and eccentricities of New York life. They wanted it policed away. While gentrification had been in process since the 1970s, and became public policy by the 1990s, it went into overdrive in the 2000s as a money-focused population moved into neighborhoods they had rarely entered before—such as my neighborhood, the East Village, a long-time center of counterculture.

The effect was the conformation of New York to a globalized norm, erasing its unique personalities. In other words, to de-subjectify its people.

4. To join in solidarity, people need un-policed public spaces.

As a queer transgender man, I came to New York to be free from the norms of suburban America, and to live among other outsiders. When New York changed in the 2000s, I felt alienated and alone. But during the pandemic lockdown, I felt free once again.

For one, capitalism took a pause. Conspicuous consumption stopped—the stores were closed so no one was walking around with shopping bags, a sight that can inspire more consumerism by stimulating a feeling of lack and desire. People stopped dressing to impress. Advertisements faded and aged. The messages of capitalism stopped playing in our ears—and those messages are all about competition, envy, and scarcity. Without that constant reinforcement, we were free to think and feel other thoughts and feelings.

“New York became more humane and liberated during lockdown.”

In my private practice, many of my patients described feeling free of their internal critical voices. They felt more relaxed and less pressured to constantly be more successful—the messages of internalized capitalism, constantly telling us that we’re not good enough and must compete for resources.

Many of the people who stayed behind in the city were outsiders—outside the center of the white, straight, middle-class. And we were literally outside, in the streets and parks, in protest marches and dance parties, and we turned the tragedy of the pandemic into an occasion for joy, love, mutual care, and social justice. New York became more humane and liberated during lockdown. In this unexpected way, the pandemic opened a doorway to hope for a better world.

5. The system does not want us to be free.

In the spring of 2021, the city reopened from lockdown and the people who had left returned, along with tourists, students, and more hyper-normal newcomers. Rents skyrocketed and many people were evicted from their homes. The police took over our public parks, harassing and arresting homeless people, queer and trans people, Black and brown people, as they enforced “quality of life” regulations. But whose quality of life? The police turned off the music that we’d danced to all year, putting an end to our joyful celebrations of solidarity. Social control came back and again I felt squeezed, dominated, and alienated.

The processes of capitalism, paused by the pandemic, kicked back into high gear. I heard people talk more about feeling pressure to improve themselves. Capitalism takes over our minds. It is a social virus.

It became clear to me that the hyper-normal people are treated as valuable commodities because they enforce the norms of capitalism and they police public space through social control. They are super-spreaders of this mindset. The system does not want us to see this. It wants us to go back to sleep, to be disconnected from each other, to be in conflict. As an accidental social experiment, the pandemic lifted the veil.

To listen to the audio version read by author Jeremiah Moss, download the Next Big Idea App today: