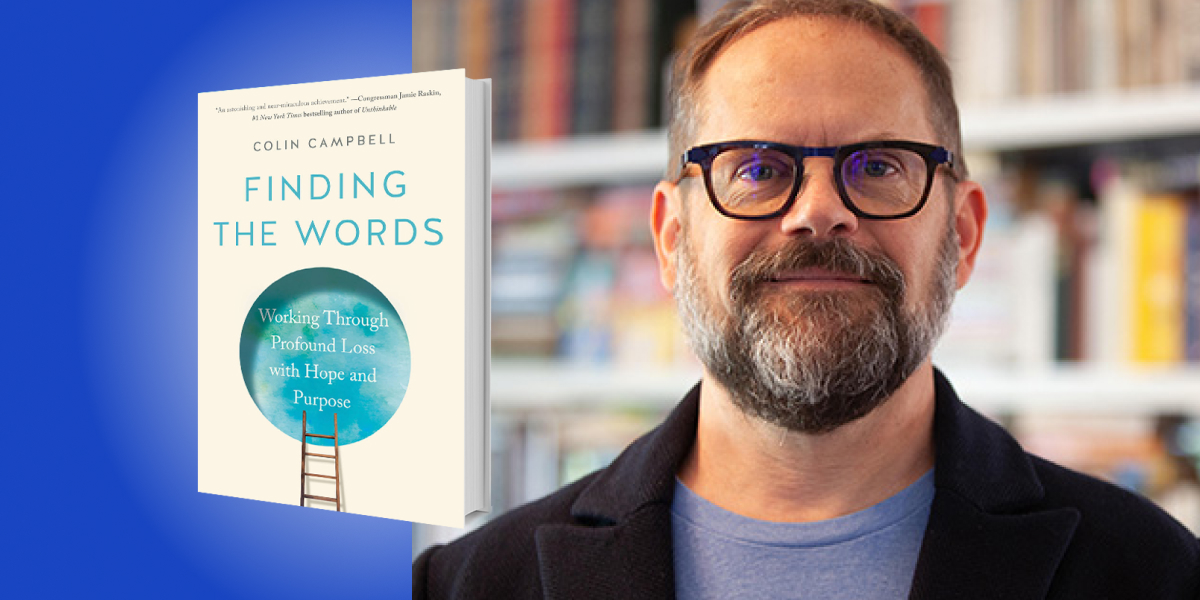

Colin Campbell is a writer and director for theater and film. He and his wife wrote and directed the short film Seraglio, which won Deauville’s Grand Prix and was nominated for an Academy Award. He teaches screenwriting classes at Chapman University and theater at California State Polytechnic University, Pomona. He wrote Finding the Words after his two teenage children, Ruby and Hart, were killed by a drunk driver.

Below, Colin shares five key insights from his new book, Finding the Words: Working Through Profound Loss with Hope and Purpose. Listen to the audio version—read by Colin himself—in the Next Big Idea App.

1. Grief doesn’t need to be mysterious.

People kept telling me that everyone grieves in their own way and in their own time. Maybe some mourners find that comforting, but I wanted some wisdom, or a framework to help me understand what it means to grieve—what was happening to me. Telling me that we all grieve in our own way made it all feel so mysterious and lonely. But, in fact, when I spoke with other mourners, I found shared wisdom. There was a commonality to our struggles.

I don’t believe we grieve in our own way. We might avoid grief in our own unique ways (through compartmentalization, distraction, drugs or alcohol, isolation), but I believe the central process of actively grieving is the same for all of us. We all need to find the words to talk about both the loved one we have lost, and about our own pain. We need to share our love and pain and have it witnessed and acknowledged. It’s how we process loss, honor our dead, and integrate our new painful reality. Talking about and trying to understand our complicated and overwhelming feelings helps stave off denial and despair. It allows us to ultimately accept that our loved one is gone.

The other problem with saying we all mourn in our own way is that it ignores that grief is a communal activity. When someone dies, they are not just mourned by their parents or spouse, children or siblings. A death is like an earthquake. There is the epicenter of loss, but then grief extends out in rings of devastation. It is important that the people at the center are connected with all the people who have been rocked. They are on a journey together. Their grief is shared. It’s the same for joy and happiness. We invite people to weddings, graduations, and baby showers, so why wouldn’t we invite people to our grief? Sharing the good and the bad makes the journey more bearable and so much less lonely.

2. Bring as many people as you can on your journey of grief.

I remember sitting in grief groups and hearing the same refrain from fellow mourners: that they had lost most of their friends and family because these people abandoned them in their time of need. There was so much anguish in their feelings of betrayal. These mourners had suffered a second terrible loss.

I could feel the same thing happening to me. Many of my friends didn’t know what to say and some simply stopped reaching out after the funeral, because they were too scared that they might say the wrong thing and upset me. I was in danger of becoming bitter and writing these dear friends off forever. But the reality is, if the situation were reversed, I would be holding back too, waiting for my grieving friend to reach out first. I too would be scared to talk to them about the person that had died. Many of our friends and family do not know what to say, so it is up to us to help them help us. I know it seems unfair that it’s our job to educate other people about grief, but we’re the only ones who know exactly what we need.

“Many of our friends and family do not know what to say, so it is up to us to help them help us.”

A few days after the funeral, I developed what I called my Grief Spiel. I would pull each friend aside individually and tell them that it was okay to talk about Ruby and Hart and the car crash and my grief. In fact, I needed to talk about all those things. I couldn’t really talk about anything else in those early days of fresh grief. I wanted to laugh and cry with friends. I reassured them that they couldn’t trigger me, because I was already triggered all the way. My friends found it incredibly useful to get this guidance. It enabled me to have the conversations I needed and prevented me from feeling bitter and isolated. If you can avoid it, please don’t grieve alone.

3. Lean into the pain.

Grief is scary. It can feel like if you start crying, you’ll never stop. And if you let yourself feel the pain, you won’t bear it. But that’s not true. Every wave of grief passes. Sometimes those waves can feel enormous, but you can ride each one out. The pain is deep because our love is so deep. The pain of grief is natural, and we need to feel it. We can’t skip it or speed it up. Sooner or later, everyone must grieve.

Two days after the burial, I was in my living room looking up at huge photos of Ruby and Hart. It was comforting to gaze into their smiling faces and still feel their presence in the house. Except this morning it wasn’t. It was scary. I was seized by the terrors of early grief, and I looked away from their photos.

In that moment, I had a powerful epiphany. I realized that my fears had the potential to drive me away from my own children. I was in danger of running from everything I had left of Ruby and Hart: my memories of our lives together. Turning back to face the photos, I shouted out loud through tears, “I am not afraid of you!” I wanted Ruby and Hart’s spirits to know that my love was strong enough to handle the pain. I would fight for our love to be felt in my heart, no matter how scary it was. If we want to feel the joy we shared, we have to feel the pain too. They go hand in hand now.

“I wanted Ruby and Hart’s spirits to know that my love was strong enough to handle the pain.”

Paradoxically, we lean into the pain of grief so that we can let that pain go and access the joyful memories instead. The idea here is not to wear our pain as proof of our love. Being in pain is not the goal of grieving, quite the opposite. Our loved ones don’t want us writhing in pain; they want us to hold on to the joy they gave us in life, but to feel that joy, we have to allow ourselves to feel the ache as well.

4. An important part of grieving is wrestling with rage.

We’ve been robbed. The universe has taken something or someone away forever and we were helpless to prevent it. That sense of injustice can fill us with rage. If we don’t own that anger and find ways of exercising and exorcising it, we can be in danger of unleashing it on our closest friends and family—the very people we need most on our journey through grief.

I wanted to spare my friends, family, and myself from all that anger. So early on I searched for healthy and productive outlets for my outsized emotions. One early practice of my wife Gail was to use journaling as a way to get her venom out. Professionally, Gail is a take-no-prisoners comedy writer. Personally, she’s a kind, loving person who doesn’t want to be cruel or hurtful. Her way of satisfying these competing needs was to devote sections of her journal to something she calls the “Hate de Jour,” using it to vent angry grief feelings via scathing and comedic takedowns of anyone or anything that pissed her off that day. She got to express her pain in a healthy and harmless way. I happily joined in. We would often regale each other with vitriolic tirades, but we were careful to keep our rants to ourselves. We weren’t trying to cause pain to others, we were simply allowing ourselves to be petty and mean in the privacy of our own home. It was a harmless, creative outlet for our rage.

Another more positive tool to handle the rage was performing random acts of kindness. For example, when I was driving my car and feeling rage building up, I found that if I, say, pulled to the side to let a motorcycle pass, or let someone merge in front of me, I would get a friendly wave of thanks and that helped dispel some anger.

“If I acted kind, I started to feel kind and then actually become kind.”

My behavior was in a way aspirational—even though I didn’t feel kind, I was doing something kind in the hopes that it would change my state of mind. And it very often worked. If I acted kind, I started to feel kind and then actually become kind. Kindness is the best antidote to rage. I think it’s why so many mourners memorialize their dead with acts of generosity.

5. Say yes to everything, even though you want to say no.

One of the most important parts of our journey through grief is the act of re-engaging with life. After Ruby and Hart were killed, I didn’t really want to live without them. It felt like I was drifting, untethered, and disconnected. Everything was unreal. I didn’t like that feeling and knew instinctually that I had to work to reconnect. I had to make an effort to care about life again. So, in the early days of grief, I decided to simply say yes to everything. If a friend offered to take a walk, I said yes, or if they offered to take me to grief meditation, or grief yoga, or skeet shooting, or hiking, or a cup of tea—I said yes to all of it. Even though I wanted to hide away in my bubble of pain, I said yes. Having a blanket policy like that made it easier for me in my early grief, when making any decision felt terribly challenging. In the end, some of those activities weren’t right for me. But that’s okay. I tried them, that’s what matters. And it helped me discover which actions did give me some solace and a sense of connection.

In those early days, I felt totally disconnected from any sense of purpose in my life. I trusted that re-engaging with other people would ultimately lead me back toward meaning. In the end, it helped. I think we have to go out into the world in order to find purpose. It begins with other people.

But actively trying to re-engage with life after loss is very challenging. We have to overcome a profound desire to curl up in a ball all alone in bed, and we also have to struggle with survivor guilt. At times it felt as though I didn’t have a right to a full life, that I was betraying Ruby and Hart and my grief if I allowed myself to feel pleasure or happiness or plan for a future without them. Just as I need to wrestle with my feelings of loss, I also need to grapple with guilt and learn to live alongside it. My grief and guilt aren’t going anywhere, so I have to learn to navigate them both. The best way to do that is to stay engaged with life and embrace the challenges. As the renowned psychiatrist and Holocaust survivor Viktor Frankl wrote, Say yes to life.

To listen to the audio version read by author Colin Campbell, download the Next Big Idea App today: