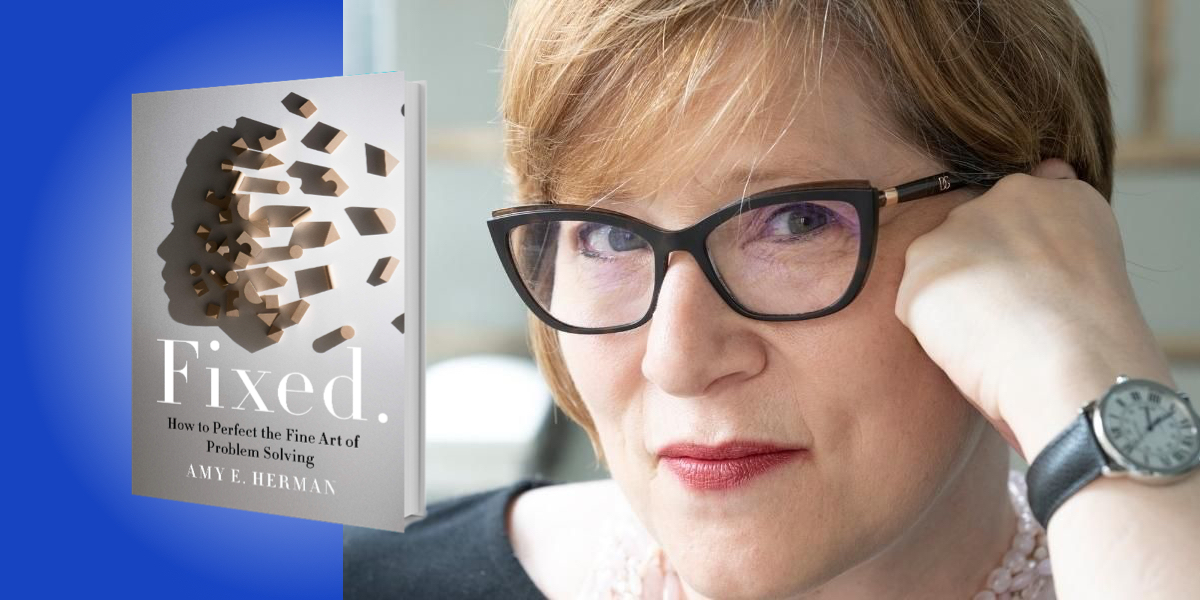

Amy Herman is a lawyer and art historian who travels the world teaching people—from special operations forces to trauma nurses to librarians—how to look at art to enhance perception skills and solve problems. Her new book looks at how an artist creates a work of art as a template for problem solving, specifically through the steps of crafting, prepping, drafting, and exhibiting.

Below, Amy shares 5 key insights from Fixed: How to Perfect the Fine Art of Problem Solving. Listen to the audio version—read by Amy herself—in the Next Big Idea App.

1. Embrace the unfamiliar.

In this pandemic, we have all embraced the unfamiliar. For example, we needed to make a seismic shift from connecting in person to meeting virtually—almost overnight. We lost our identity from the neck down, but if we didn’t embrace it, we got left behind.

Instead of closing the door to something you don’t like, leave it open a crack to see what light filters in. You might like what you see after all, and make it part of your approach to problems. People often tell me “I hate modern art” or “I don’t get abstract art.” But something unfamiliar doesn’t have to go hand-in-hand with being disliked. It is fine to say, “I really like this. I’m not sure I understand what the artist is trying to say, but the colors and lines are quite soothing.”

When we embrace the unfamiliar in works of art, and articulate what we don’t understand, it’s easy to see how that can translate into working with people of different values, cultures, and operating procedures. Embracing the unfamiliar when looking at art provides tools to use in many other situations.

“Instead of closing the door to something you don’t like, leave it open a crack to see what light filters in.”

2. The importance of why.

Ask yourself and your colleagues (as many times as you need to) why you are doing something. Having an overarching objective—even to brainstorm creatively—keeps people on track and reduces the chance of problems creeping up.

Asking ourselves why we like or dislike something is the time to identify and reconcile biases. We need to be able to explain, in explicit terms, why we feel a certain way. Not only does this clear the air, but it also becomes an exercise in self-realization. Understanding why you feel a certain way about a person, idea, product, or objective helps pave the way for more productive work going forward. We can’t assume that we are all on the same page, so laying the groundwork for why—explicitly and precisely—allows us to get there efficiently, together.

If you articulate the why for actions, plans, and instructions, and reiterate them as often as necessary, there is much less room for straying from a stated objective to solve a problem. Why used to be the annoying question your toddler always asked, but they did so for good reason. We should be naturally inquisitive, and if more people asked why, many things would be much more efficient.

3. Measure twice, cut once.

Take the time to plan and think about what you are going to say and do. Artists have limited resources and have to work with those limitations in mind. Speaking off the cuff not only ensures that you will omit something you want to say, but also conveys to your listeners, coworkers, or family that you didn’t think them worthy enough to take the time to prepare what you have to say. Time is our most precious commodity.

“We cannot solve our problems with the same thinking we used to create them.”

When being deliberate and measuring carefully, think about what might be missing. You know what you are seeing, but what might be escaping? Consider all the angles—what is there, and what might be hiding. You’ll get a more accurate picture before marking that canvas or chiseling that marble.

When it comes to measuring and cutting, keep in mind Albert Einstein’s famous quote, “We cannot solve our problems with the same thinking we used to create them.” Get outside yourself, and look and think purposefully before making any big moves to avoid unwanted errors. If we plan on thinking things through and articulate that plan before taking action, solutions become that much more attainable.

4. Set a deadline.

Artists and creative types agree that deadlines are often dreaded, but necessary—they stimulate creativity and completion. Da Vinci carried the Mona Lisa around with him for years, constantly tweaking it before injuring his hand, and never really completing it to his satisfaction. Perhaps da Vinci should have thought of a deadline.

Deadlines are essential to problem solving; they give a problem importance, parameters, and a vision for completion. Everyone wants to see the light at the end of the tunnel, even if it is an oncoming train. Sometimes, though, we have to shift our perspective on deadlines to make them useful. Deadlines can breed confidence. In trying to reach a deadline, artists often discover colors, processes, and patterns they had never contemplated, and which will enhance the final work of art. Deadlines give a template to meet goals in a given time frame, but don’t just keep your eye on the finish line—embrace the journey, because who knows what innovation or solution might appear in the process.

“Deadlines are essential to problem solving; they give a problem importance, parameters, and a vision for completion.”

I wish I had deadlines for projects that are always looming, but never demanding—like cleaning my closet. Don’t forget to celebrate deadlines that are met. We are too quick to get absorbed in the drama and anxiety of getting to the finish line, but then don’t celebrate what has been accomplished. Celebration instills confidence. It reminds us of how good we really can be when the pressure is on.

5. Find common ground.

One of the things I have heard (annoyingly) repeatedly in the last 18 months is that we are all in the same boat. We are not, and never have been. Before the pandemic hit, we all had different resources, capabilities, strengths, and weaknesses, and we needed to look broadly and objectively at those inequities.

The truth is, we were all in the same storm. As that storm begins to abate, we need to recognize, once again, that we are still not in the same boat. We need to look at our resources—human, financial, and temporal—realistically, and move ahead accordingly. Just because we are in different boats doesn’t mean we can’t find common ground. Finding that sweet spot where our Venn diagrams intersect provides a great platform from which we can solve problems. There is an African proverb that says, “If you want to go fast, go alone. But if you want to go far, go together.” Common ground on all issues: make it a priority.

When attempting to solve problems, put your visual intelligence to work: try to see what others don’t, and aspire to be, in the words of Henry James, the person on whom nothing is lost.

To listen to the audio version read by author Amy Herman, download the Next Big Idea App today: